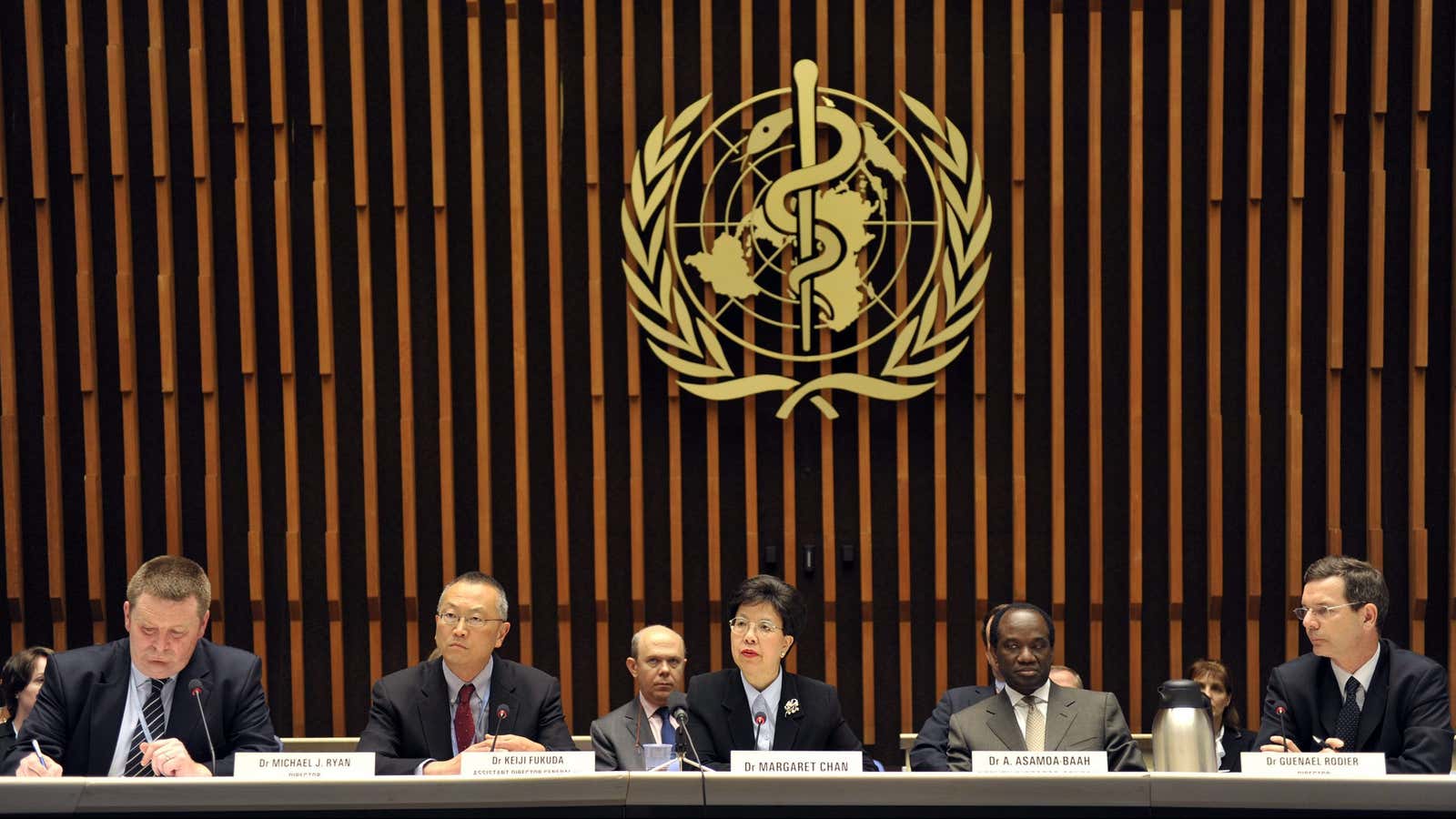

It’s both a uniquely good and a uniquely bad time to be the World Health Organization (WHO).

Since the start of the novel coronavirus pandemic, the global health body has become near indispensable, collecting and analyzing data from 194 member states, supporting poor countries with weak healthcare systems, and helping coordinate the global search for therapeutics and a vaccine. Pushed aside for years by countries who underfunded it and only gave it the time of day when faced with a deadly health emergency, the WHO now has a good chance to make a strong case for itself.

At the same time, the WHO is under a microscope. World leaders have scrutinized every decision it has made since Dec. 31, when Chinese authorities first notified the agency that a mysterious kind of pneumonia was spreading in Wuhan. It is routinely accused of kowtowing to China, including in its dealings with Taiwan. For this reason, it has apparently lost its biggest source of funding.

Now, Australian prime minister Scott Morrison is suggesting governments consider rethinking the WHO’s governance structure and enforcement powers in order to better equip the global public health agency to deal with future pandemics. Morrison’s proposal is so far light on details. It’s also unclear who else is on board, though he said he discussed it with US president Donald Trump, France’s Emmanuel Macron, Germany’s Angela Merkel, and New Zealand’s Jacinda Ardern. Reuters reports that the Australian government plans to propose the changes at next month’s annual meeting of the WHO’s decision-making body.

By making the proposal, Morrison has revived a perennial debate among states about how much of their sovereignty they should sacrifice for the benefit of global governance. When it comes to public health, there is precedent for ceding some of that independence for the common good—and the devastating results of the coronavirus pandemic seem to provide a good argument for doing just that.

According to The Sydney Morning Herald, Morrison wants the WHO “to be given the same powers as weapons inspectors to forcibly enter a country.” Presumably, this is a reference to the International Atomic Energy Agency, which can send teams into countries that are signatories of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and other agreements to inspect nuclear facilities.

The problem, experts say, is that it would extend the mandate and enforcement powers of the WHO to a level that many member states have long refused to allow. Even now, it’s hard to imagine US president Donald Trump, who has been openly hostile to the UN and other multilateral groups, agreeing to such a change.

In 2005, WHO member states passed a revised version of the 1969 International Health Regulations (IHR), which govern the world’s response to deadly diseases. Rebecca Katz, director of the Center for Global Health Science and Security at Georgetown University Medical Center, and researcher Anna Muldoon, wrote in a 2011 book about global health diplomacy that “early drafts of IHR 2005 included the ability for the WHO to send a team into a country to verify an incident.” But the US, Iran, and China, among others, feared this would give the WHO too much power. In the end, “any kind of explicit language on verification” was removed.

More broadly, WHO member states have long been reluctant to give the WHO too much power, leaving it with few tools for enforcement. “The only power the organization has is to name and shame countries that do the wrong thing,” said Adam Kamradt-Scott, an analyst at the Centre for International Security Studies at the University of Sydney, adding that “every time the WHO has criticized a member state, other member states have collectively come together to punish the organization.”

So there’s not much the WHO can do to sanction member states who don’t respect their obligations. If the WHO has a disagreement with a member state (pdf, p. 34), the World Health Assembly—meaning all the member states of the WHO—is responsible for resolving it. If two member states have a dispute, they can agree to refer it to the WHO director general, “who shall make every effort to settle it.” Otherwise, they can both agree to resolve it through arbitration.

In the end, Morrison’s proposal seems unlikely to garner much support. As a representative for the WHO told Quartz, “any change to our role or mandate would have to be reviewed and approved by our 194 member states.”