This is huge: China may allow its first-ever corporate bond default

When it comes to China’s financial system, the unexpected default of a tiny solar company might do more for reform than the 32 pages of central government planning that premier Li Keqiang announced in a government work report earlier today.

When it comes to China’s financial system, the unexpected default of a tiny solar company might do more for reform than the 32 pages of central government planning that premier Li Keqiang announced in a government work report earlier today.

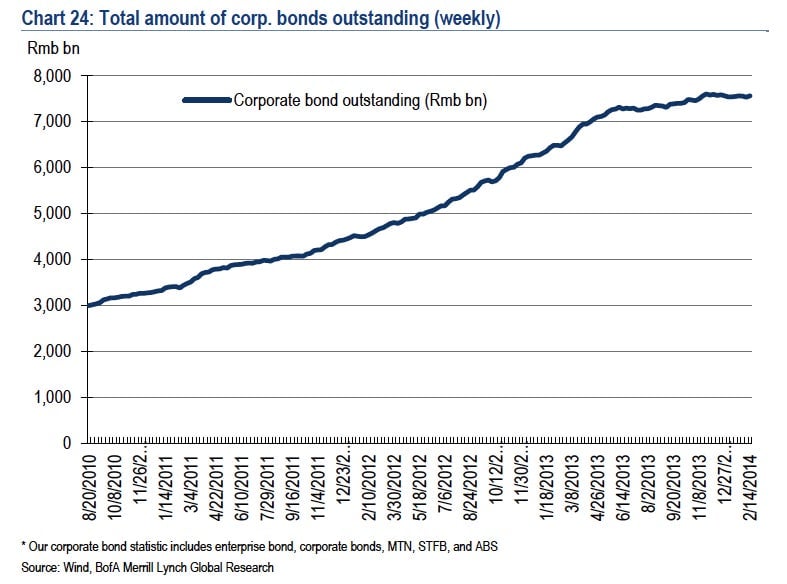

Specifically, the default of Shanghai Chaori Solar Energy on its 1-billion-yuan ($163-million) bond might help speed the pace of market reform. If the government refuses to bail out the maker of solar cells and panels, this will be the first bond default in the People’s Republic of China’s history. Yes, that’s right: in China’s whole $1.5-trillion publicly traded corporate-debt market, no company has ever defaulted.

Letting this default happen could be a massive deal for a couple of reasons. For one, a default will force the market to start pricing in risk, explains Leland Miller, president of China Beige Book (CBB) International, a research firm.

“Anything that can inject risk in the system and differentiate what is backstopped and not backstopped is a very good thing for China,” says Miller. “Right now everyone thinks the banks are backstopping everything and that the government is backstopping [the banks]. And that’s very, very dangerous, especially in a year where you’re likely to see a lot of defaults.”

Until now, high-profile investment products on the brink of default have all been bailed out at the 11th hour. It’s not surprising that people assume that someone—banks or the government—will recoup their losses. As we’ve reported, more than 43% of the 10.9 trillion yuan ($1.8 trillion) worth of outstanding trust products come due in 2014.

Chaori has a wide base of retail investors, notes Fitch, a bond-rating agency. That may be why, when things started looking ugly back in February of 2013, the Shanghai government told retail bond investors that it would ask Chaori’s bond underwriter—a joint venture called China Securities backed by a wealthy, powerful central-government division—to cover the principal.

The company now says it won’t be able to repay (paywall) all the interest when the bond comes due on Friday. This may signal that the government will finally allow corporate defaults—a crucial move toward letting the market dictate interest rates, which is one of its key reform goals.

What happens next? In theory, knowing that they might lose money means investors will start charging way more for what they loan out. That, Fitch says, ”could pressure frailer companies’ liquidity, especially in sectors challenged by cyclical downturns and persistent capacity surpluses.”

In other words, more defaults.

In that vein, David Cui of Bank of America/Merrill Lynch says that if the default—particularly on the bond’s principal—occurs, we’ll be nearing “the Bear Stearns stage,” meaning the point in 2007-2008 when “the market started to seriously re-assess sub-prime debt risk.”

Bank of America/Merrill Lynch made similarly dire predictions during China’s last almost-default episode, so some suggest they are crying wolf (Bear?). But while it took a year from Bear Stearns’ bailout to the freeze-up of shadow banking that happened with the Lehman collapse, Cui points out, it could take even longer for China to hit that point, due to the lack of transparency in the market.