Privacy may have already seemed antiquated before the coronavirus pandemic. We’ve reached the point where Facebook, Google, and an army of third-party data brokers possess more information on human behavior than any government in history. Our smartphones betray our location. Surveillance companies create uncannily accurate facial-recognition databases from the photos we post to social media.

It’s no surprise that governments are now turning to such tools in the interest of public health. Around the world, authorities have released or plan to roll out contact-tracing apps. The idea is that if someone becomes infected with Covid-19, anyone who that person may have exposed can be alerted or found.

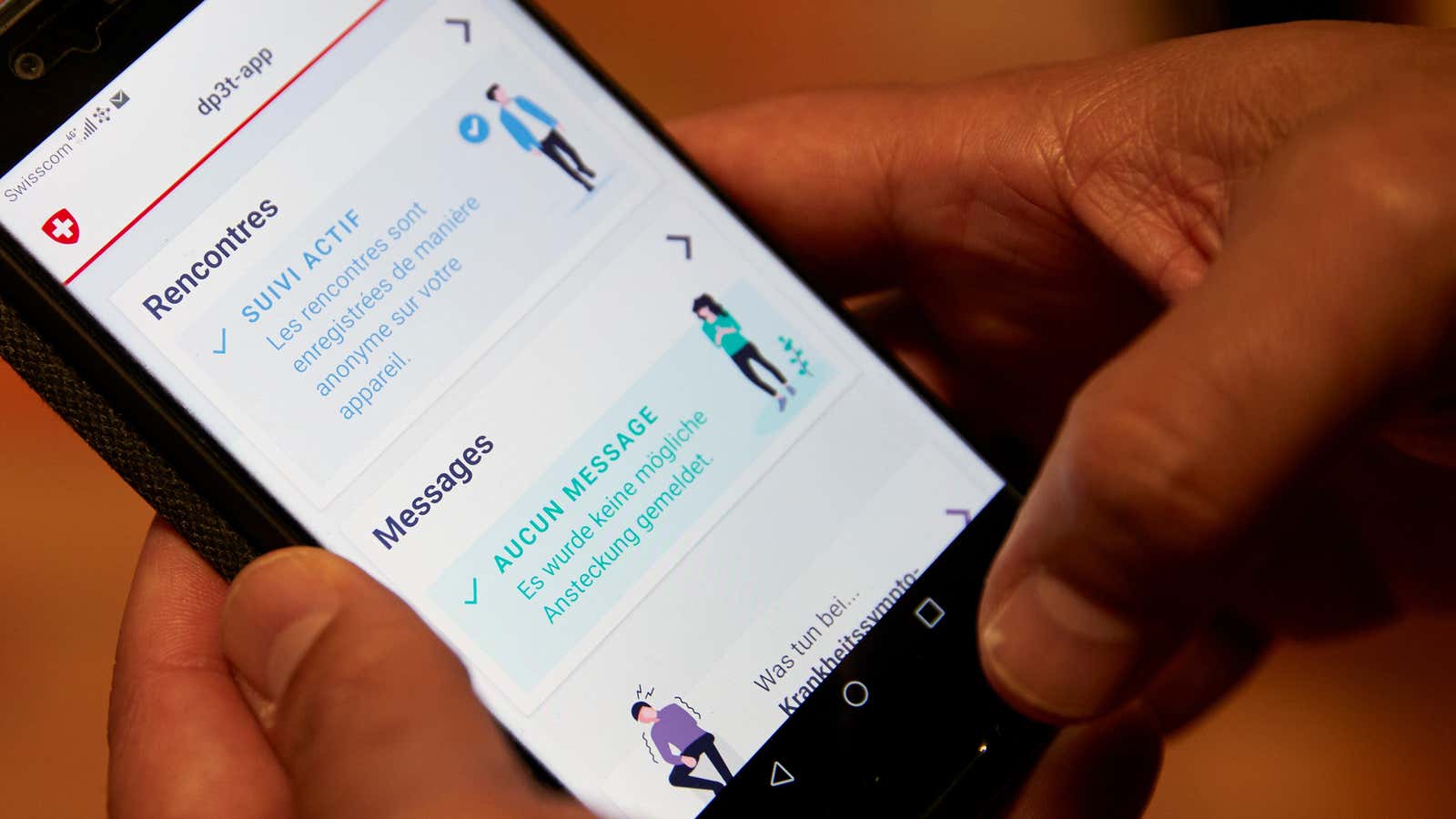

Big Tech, no stranger to tracking your smartphone, wants to make sure governments are doing it carefully. Apple and Google released a beta API this week that health authorities can use to develop such apps. It uses Bluetooth, a proximity-based approach meant to reduce privacy fears by keeping data decentralized and the identity of disease carriers anonymous.

But critics note that even Bluetooth has shortcomings and security risks. And they’re even more skeptical of contact-tracing systems that use location data and centralized databases, as they do in China, India, South Korea, and even Norway.

The UK’s National Health Service announced this week that it would store data from its own contact-tracing app on a centralized server. In the US, Utah released an app that reveals personal data to public health authorities—and to some employees of the firm that designed it. Even the EU, with its strict data protections, will implement digital tracing of citizens at an unprecedented scale.

Such data collection is already having unintended consequences. South Korea’s coronavirus-tracking apps have made it possible to suss out the identities of those infected, leading to public shaming.

As regions lift their stay-at-home orders, contact tracing will let authorities better track Covid-19’s spread. It will also give governments and companies a treasure trove of information on our health and movements—and create a precedent to request more later. The danger is when the public becomes used to it.

This essay was originally published in the weekend edition of the Quartz Daily Brief newsletter. Sign up for it here.