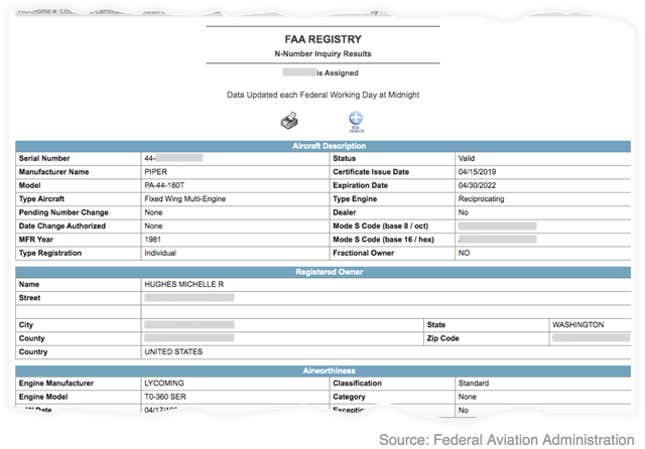

When Michelle Renee Hughes registered his new airplane with the Federal Aviation Administration last February, he submitted all the necessary paperwork, including a signed bill of sale showing he bought the 1981 Piper Seminole from a private seller for $115,000.

Although the return address on the envelope didn’t match the address listed on the registration form, Hughes included the standard $5 registration fee and everything else seemed in order. A couple of weeks later, the FAA registry officially transferred ownership of the aircraft, a twin-engine, three-passenger plane with a range of nearly 1,000 miles, over to Hughes.

Hughes, who identifies as male but registered the Piper as “Ms. Michelle Hughes,” then listed the plane for sale on on the online marketplace AeroTrader.com.

“I own a 1981 Piper PA-44-180T,” said Hughes’s ad, which asked $125,000 for the plane. “I have proof of ownership in hand from the FAA. The Plane located at Shelton, WA. The plane is well cared for and want to find it a new home. I can even accept trades, negotiated on the price.”

A potential buyer responded to Hughes’s listing, but said he didn’t have enough money to buy the Piper outright. In a series of emails and text messages, Hughes offered to arrange financing and floated the idea of selling 50% of the plane for $62,500 and sharing ownership of it.

“You can check it out anytime you want to,” Hughes texted. “The door is unlocked. The plane is at Shelton, WA airport. Feel free to fly it to Kent wa [sic] airport. My car wont [sic] make it to Shelton.”

Nearly three weeks went by. An impatient Hughes texted the prospective customer, saying that someone else was interested in buying a half-share of the Piper. “If I don’t get something today, I will have to sell to someone else,” he wrote.

What Hughes didn’t know was that the “customer” was in fact an undercover agent from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). According to a criminal complaint filed in federal court, the paperwork Hughes sent to the FAA was phony, something that only came to light when a worker at the Washington State Department of Transportation placed a routine call to the Piper’s previous owner to confirm their cancellation of the plane’s registration. The confused owner, a US Navy doctor in Gig Harbor, WA, said he hadn’t sold his plane, nor did he intend to.

“After the aircraft is registered on paper, the new (fraudulent) owner then sells the aircraft to an unsuspecting buyer, who pays money but does not receive the anticipated airplane in return,” the complaint explains. “The new (fraudulent) owner then absconds with the money.”

Scam artists have used this form of identity theft to illegally take “ownership” of homes, boats, cars, and now, airplanes. According to the Federal Trade Commission, consumers reported losing nearly $2 billion to fraud in 2019. Nearly a quarter of identity theft victims have been victimized before. Seniors, social media users, members of the military, and the deceased are at particular risk for this type of crime.

An FAA official cited in the complaint told investigators that the agency “takes all documents at face value,” and “does not question anything unless the applications are incorrectly completed or contain missing information.” The official, who declined Quartz’s request for comment, told DHS that he has seen other, similar cases.

DHS agents met with the Piper’s owner, identified in court documents as “J.M.,” whose signature looked nothing like the one on Hughes’s purported bill of sale. J.M. said he didn’t know Hughes, and had never met him before, adding that he had had since installed an anti-theft device in his airplane to keep it safe.

At the same time, Hughes was trying to sell a second airplane he didn’t own. About a month after successfully transferring J.M.’s Piper into his name, Hughes did the same thing with a twin-engine Cessna Citation Mustang business jet belonging to a Washington State man identified in court documents as “A.E.”

Written into a maintenance agreement A.E. had for his plane with Textron Aviation was a clause that required the contract to be rewritten if the aircraft changed hands. At the end of May, a customer service supervisor at Textron informed A.E. that the company had received a change of ownership notification for the Cessna. A.E. said he hadn’t sold the airplane. Textron sent A.E. copies of the documents submitted to the FAA by the new “owner,” Michelle Hughes. Among them was a phony bill of sale, showing Hughes had supposedly bought the Cessna for $1.5 million.

Hughes tried to sell the plane to a Wisconsin aircraft broker. The broker purchased a list of all registered Citation Mustang owners in the US, which now included Hughes.

“My name is Michelle Hughes and I am willing to sell,” Hughes wrote. “I have the Cessna Citation Mustang, [tail number]. I am still interested. How soon is the client interested in purchasing it? I can even do a Bill of sale. I like to know how soon will I receive the funds? Do you mail me a check or do a direct deposit? The plane isn’t represented by a broker. I am asking for $2.5 million. Sincerely, Michelle Hughes.” He also left a voicemail for the broker, with his phone number.

For reasons not explained in legal documents, the Wisconsin broker interested in the plane contacted A.E., who had already reported the apparent fraud to authorities. Hughes, who has been previously convicted for fraud on both the federal and state levels, according to the federal complaint against him, was arrested a week later. His court-appointed attorneys did not respond to a request for comment.

“We were on hard times all the time, and [had been] on the streets,” Hughes’s girlfriend, Michelle Saad, who is described as his wife in court filings, told Quartz. “It was really dangerous out there and we had to survive and he was just looking for a way out for us, I guess.”

Saad, who works for a large, Seattle-based online retailer, said she remains “up against the wall” financially.

“Sometimes you have find a way to survive, whether it be honest, whether it be jumping on each side of the law,” she said. “That doesn’t necessarily make it right, but you know what I’m saying?”

Most fraudsters don’t expect every scam to be a success, said Eric Beste, a former federal prosecutor who handled multiple fraud cases during his 22-year DOJ career.

“It doesn’t have to work that often,” Beste told Quartz. “If you sell a couple of these planes, you’re off off to the races.”

Being a victim of fraud—or even an attempted fraud—can be an extremely traumatic experience, said Eva Velasquez, CEO of the nonprofit Identity Theft Resource Center, which offers free services to victims. And the Hughes case illustrates how easy it is for someone to make sweeping changes to important things like title documents without the legitimate owner even knowing it happened.

“There is this common misconception that when we’re talking about victims of economic crimes, white-collar crimes, or anything that has to do with their finances and not their physical body, that it is somehow less of a violation and doesn’t derail them in the same way,” Velasquez told Quartz. “We tend to see a lot of shock and disbelief because until you are a victim of one of these things, most people are under the impression that all of the systems that are in place to protect them, never fail.”

In March 2020, while awaiting trial, Hughes was arrested again after being caught with a birth certificate and driver’s license in someone else’s name—a violation of his release conditions. The following month, Hughes pleaded guilty to all charges. He is currently detained in a high-security federal lockup in Seattle. The Department of Justice declined to provide a statement prior to Hughes’s sentencing, scheduled for Aug. 8.

“Committing the crime isn’t too difficult—the hard part is getting away with it,” said Beste, adding, “As a fraud prosecutor, you never have to worry about job security.”