When China, Singapore, South Korea, and other nations in Asia started using tracking apps and digital tools to monitor the spread of Covid-19, some assumed that their counterparts in the west wouldn’t embrace the technology—that citizens were unlikely to consent to government surveillance. But that assumption, it turns out, was wrong.

Germany and Australia, for example, are both planning on releasing contact tracing apps that perform the same basic function: letting those who test positive for Covid-19 anonymously inform all those they’ve risked infecting. Both apps use Bluetooth, and don’t track GPS or location data. But other than that, the approach of the two Western nations are as different as night and day—illustrating a debate over how these apps should balance privacy with virus-stopping potential.

Australia’s contact tracing app, launched this week (May 12), stores the personal data of its users in a central server, owned by the Australian government and operated by Amazon Web Services. State and territory health officials will be able to access the server, and the government has promised to delete the data (including name, post code, infection status, and age range) when the pandemic is over. Meanwhile, Germany has opted for a decentralized approach for its app, expected to be released later this year. Contacts with other app users will be stored on the user’s phone. Personal data will never enter a government database or even be seen by public health officials.

Nations around the world are locked in a fierce debate about which approach—centralized or decentralized—is the best for contact tracing apps. Along with Germany, countries including Austria, Belgium, Estonia, Switzerland, and Ireland have vowed to use the decentralized method. Meanwhile, the UK, Australia, France, and Norway have released or are in the process of releasing apps that store data in central servers. In the US, apps released by the states of Utah, North Dakota, and South Dakota are also centralized.

Public health agencies in countries that have pushed for centralized apps say they would give the government access to valuable data on how people are spreading the virus in their regions. But critics warn of a future in which digital contact tracing opens up the door to even more government surveillance and potential data breaches. The debate has made strange bedfellows of Big Tech, digital rights advocates, and cybersecurity experts; Apple and Google have refused to tailor an upcoming API to centralized apps, despite protests from countries like the UK and France.

Meanwhile, the PEPP-PT, a group of EU researchers that vowed to design a unified approach to contact tracing for all of Europe, is a shadow of its former self. The group initially said it would back both centralized and decentralized methods. But last month, it shifted gears and scrapped its plan for a decentralized protocol, prompting nations like Germany (one of its original backers) and Switzerland to leave the group.

Marcel Salathé, a Swiss digital epidemiologist who was involved in the early stages of PEPP-PT, said he made his exit after it became clear that PEPP-PT would take a centralized approach. From the perspective of a scientist, Salathé said it was easy to understand why some countries would want a centralized app. “What scientist would say, ‘If I had less data, I could do better science?’ More data is always better,” he said. “The thing is every time you get more data, you sacrifice some privacy. The question is, where do you strike the balance?”

According to Attila Tomaschek, a digital privacy expert at ProPrivacy, a company that makes privacy tools like VPNs, all centralized apps pose the same problem. While the scope of the information collected by governments can vary greatly, a centralized app can be easily repurposed for surveillance beyond what the app was originally designed for.

In the event of a data breach on a central server, it likely wouldn’t matter if the information collected is anonymized. “Even anonymized data can be de-anonymized by a skilled individual and linked to specific users,” said Tomaschek. “The bottom line is that employing a centralized approach to digital contact tracing can put user data at considerable and unnecessary risk.”

“It creeps in, right? It’s not that anyone has an intention or a master plan,” said Salathé. “It’s a matter of someone saying let’s add this, and let’s add that, and all of the sudden you have a massive surveillance machine.”

Decentralized apps aren’t perfect, either. Last month, Iceland launched an app that uses GPS data to formulate a map of where users go. If users test positive, they can elect to share that data with their contacts and Icelandic health authorities. Despite the fact that it tracks location, Iceland’s contact tracing app was downloaded by nearly 40% of the population, reported MIT Technology Review. The app’s privacy policy states that it deletes all collected location data after a period of 14 days.

The combination of public pressure and technical issues is causing some to reconsider their approach.

Centralized apps won’t work on iPhones, which account for roughly half of all smartphone users in the US and the UK, due to Apple’s strict limitations on Bluetooth use. Such apps would only work if iPhones are unlocked and apps are open (Android devices don’t appear to be impacted). If two people with iPhones in locked mode come in contact with each other, it’ll be like the contact never happened. Michael Veale, a privacy expert at UCL, pointed out this weakness in the proposed NHSX app, joking about an “Android herd immunity.”

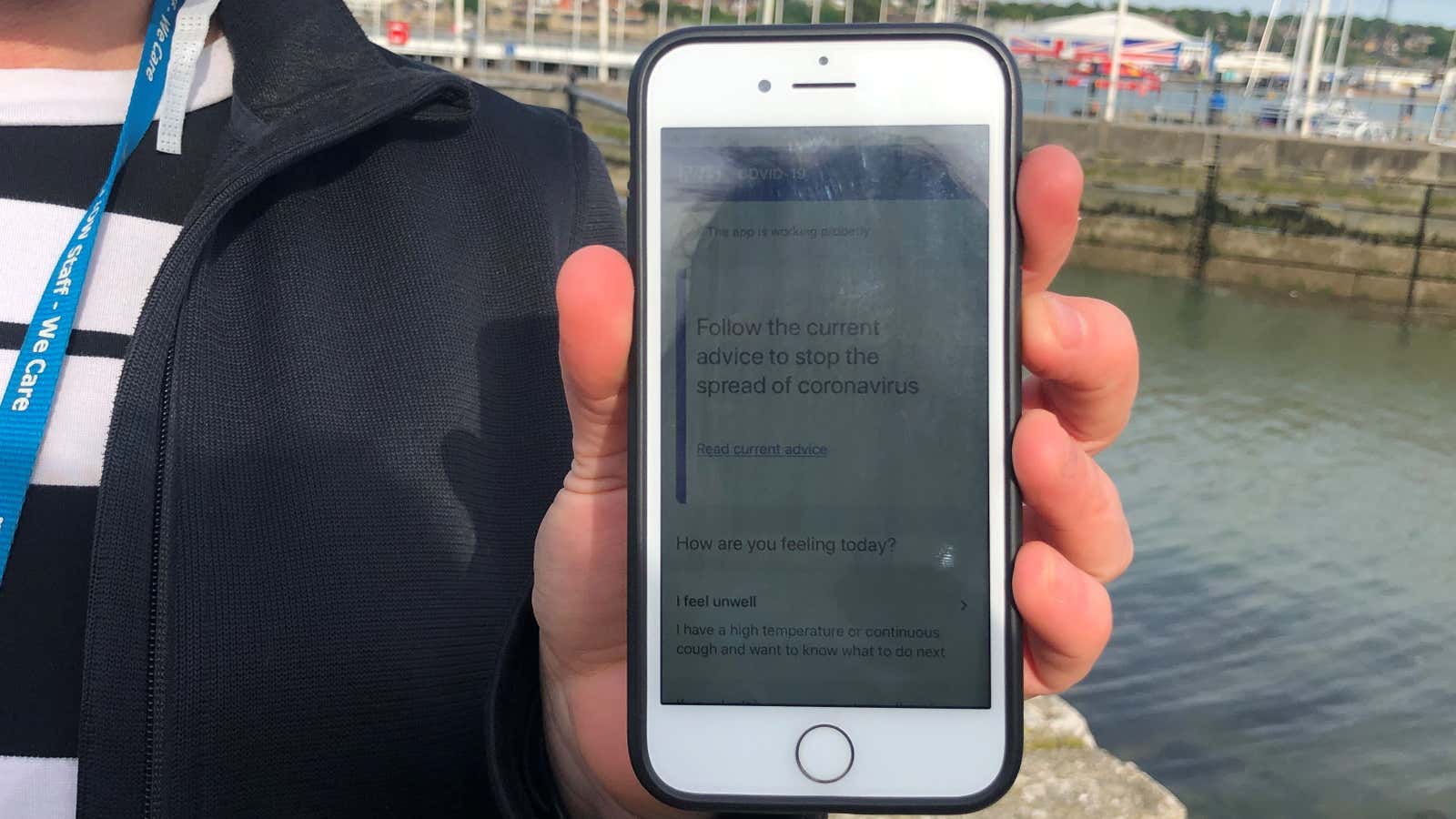

Because of that weakness, the UK this week said it will build two apps, with the second following a decentralized API that will be released by Apple and Google. The Australian government this week acknowledged that its app “doesn’t work properly” on iPhones. If Apple and Google don’t compromise on their requirements, Salathé predicts that more nations will gradually shift to a decentralized app.

If they don’t, the split between approaches could have an effect on their efficacy. Decentralized apps and centralized apps won’t be able to share information, due to the different types of data they collect. The lack of interoperability will be a problem for the EU if governments decide to require the apps for travel within the bloc.

“I’m a bit puzzled that governments will try to do the centralized approach. Because really, how else could you make it work?” asked Salathé.