Why hydrogen-powered cars will drive Elon Musk crazy

Forget the Tesla Model S. Another car of the future is finally hitting the highway.

Forget the Tesla Model S. Another car of the future is finally hitting the highway.

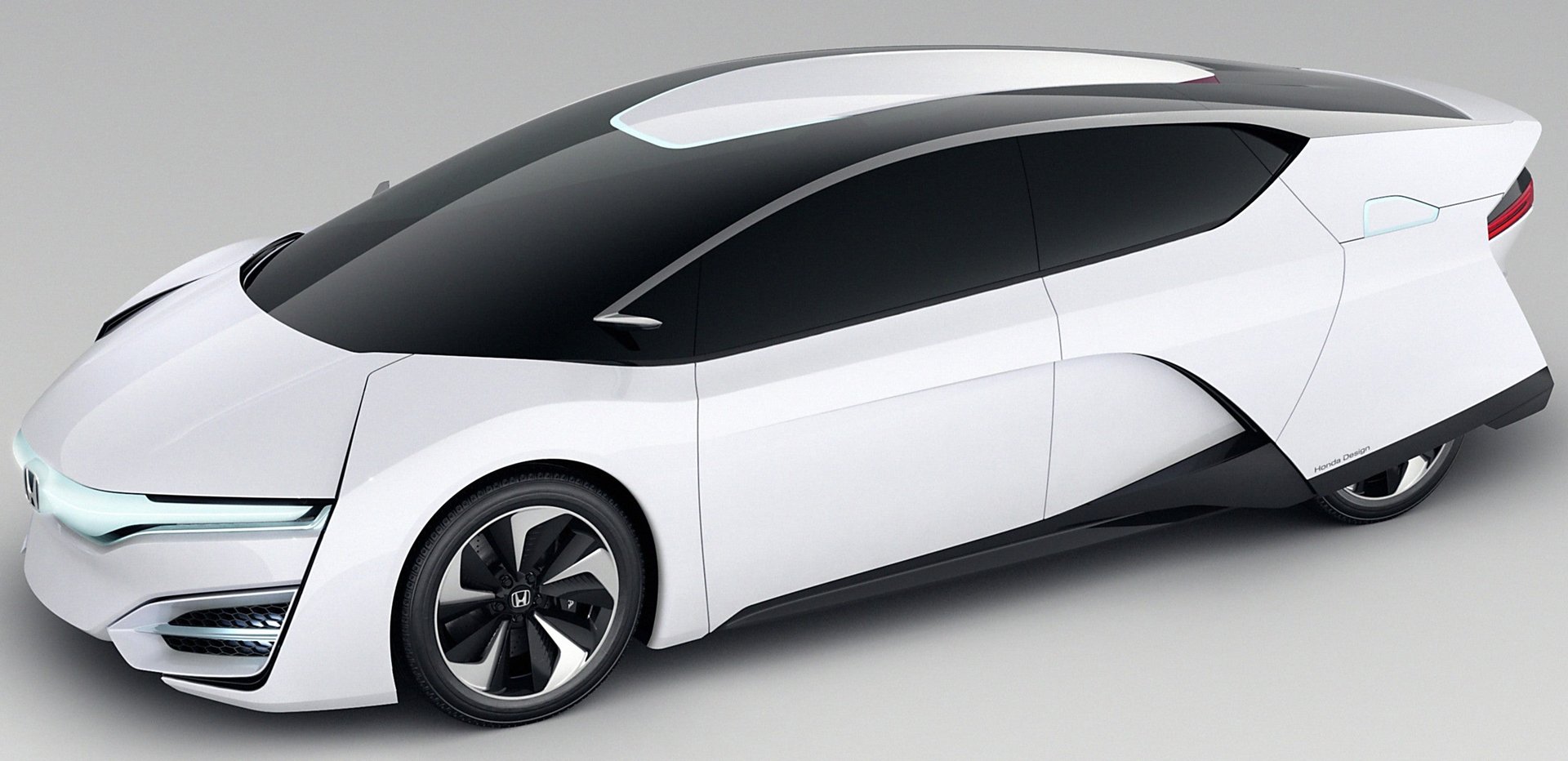

After decades of development—and no small amount of skepticism—major automakers are set to start selling hydrogen fuel-cell cars in small numbers in the US. In the coming months, a hydrogen-powered version of Hyundai’s Tucson sport utility vehicle will appear in southern California showrooms. And Honda and Toyota next year will offer Californians futuristic sedans that can travel 300 miles (480 km) or more on a tank of hydrogen gas while emitting nothing more toxic than water vapor.

The state of California, meanwhile, is putting up $20 million a year to finance the construction of 100 fueling stations, at last building former Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger’s much hyped but vaporous “hydrogen highway.” It’s been 15 years since the California Fuel Cell Partnership, a coalition of automakers, technology companies and government policymakers, was founded, but now, says Catherine Dunwoody, its director, “We’re definitely at that tipping point where we’re confident that we can launch the market for hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles.”

Up to now, the ambition of weaning drivers off fossil fuels has largely focused on hot-selling electric cars like Tesla’s Model S. (In the US, transportation alone accounts for nearly a third of the nation’s greenhouse gas spew.) But hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles may be the real game-changer.

Powered by a fuel whose supply is practically inexhaustible—every nation can be the Saudi Arabia of hydrogen—fuel-cell cars convert pressurized hydrogen gas into electricity that powers the vehicle. The hydrogen cars now coming onto the market have triple the range of most battery electric cars and can be refueled in minutes rather than recharged in hours. And hydrogen technology can be scaled up to fuel buses, long-haul trucks and other big vehicles that most current battery packs are too puny to power. “We don’t see any reason customers wouldn’t adopt this technology in exchange for a gasoline vehicle as there’s no trade-offs,” Craig Scott, Toyota’s US national manager of advanced technology vehicles, told Quartz.

Actually, there are trade-offs. One is price. When I drove a Mercedes fuel-cell prototype in 2007, a Daimler representative said it cost nearly $1 million to build the bespoke vehicle. The other is infrastructure. Today, there are fewer than two dozen public hydrogen fuel stations operating in the US—and seven of those are in the Los Angeles area. Hence Tesla CEO Elon Musk’s recent declaration that hydrogen cars were “bullshit.”

But the H-bomb is about to drop. The cost of making fuel-cell vehicles has dropped fast. And with state funding secured, a hydrogen fuel-station building boom is under way in California. The Obama administration, meanwhile, has launched an effort to take the state’s hydrogen strategy nationwide.

The rollout of hydrogen cars is about more than which road to take to the carbon-free future, though. It’s a test of two very different strategies. And it’s a showdown between Tesla, an upstart Silicon Valley automaker that grew to a $30 billion market cap—half of Honda’s—on the basis of a single electric car, and the world’s biggest car companies, who are dependent on the government to finance the first leg of the hydrogen highway.

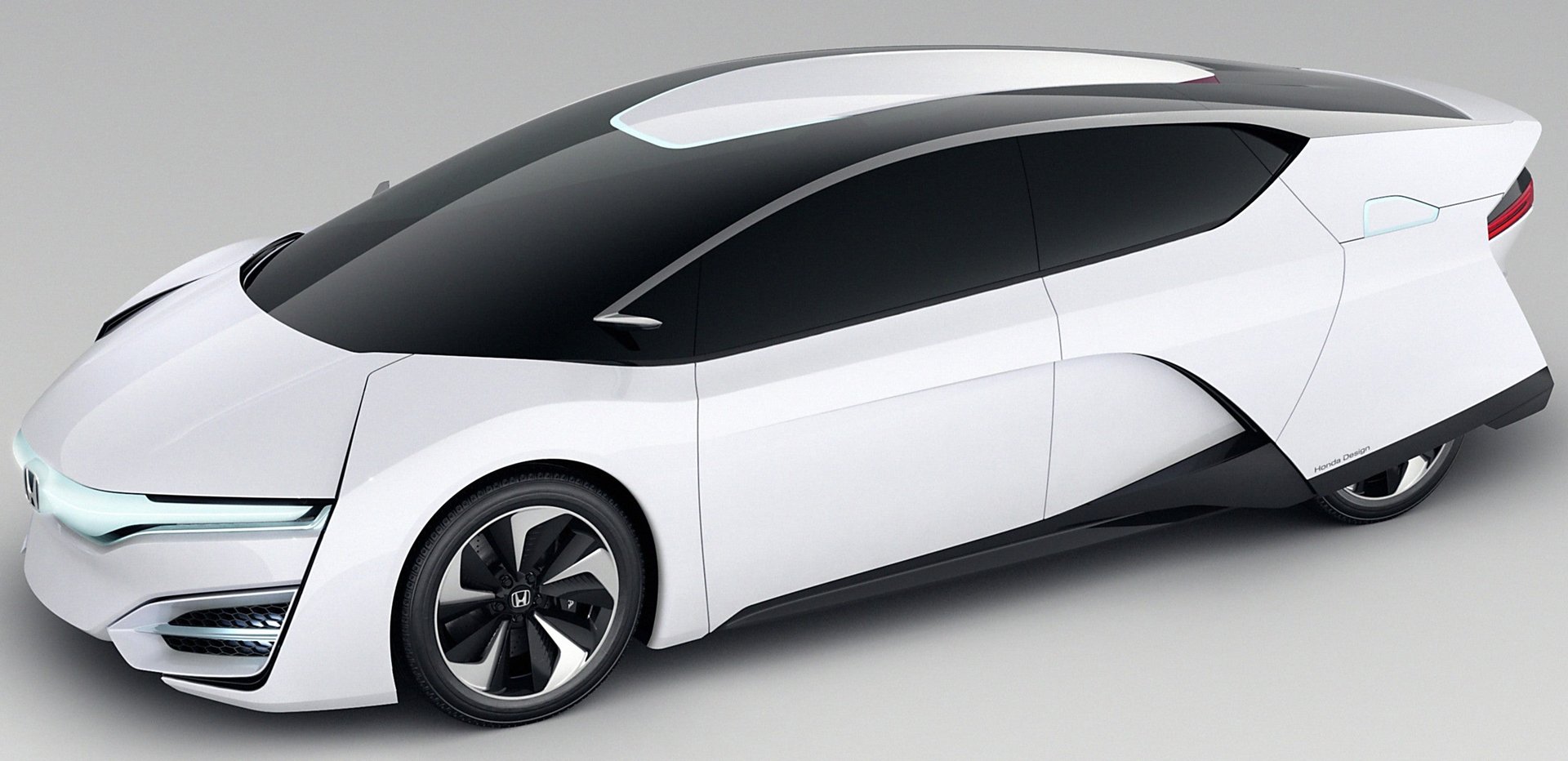

The commonest fuel in the universe

An automotive fuel cell is essentially a big battery. A pressurized tank supplies hydrogen gas that travels to an anode on one side of the cell, where a platinum catalyst splits the gas into protons and electrons. On the other side, oxygen from the ambient air flows to the cathode. In between them sits a membrane that lets the hydrogen’s protons pass through but blocks the electrons. The electrons are forced to take the long way round to the cathode, via an external circuit. That stream of electrons is the electrical current that powers the vehicle’s motor. When the electrons and protons meet again in the cathode, they combine with the oxygen and create water.

Hydrogen may be the most abundant element in the universe, but outside the centers of stars and gas-giant planets, very little of it exists in the pure and compressed form that fuel cells need. It needs to be extracted from other compounds, like water or methane. That takes energy, which means that fuel-cell cars, like electric cars, are never truly “emissions-free” unless the hydrogen is produced from renewable sources like solar, wind or biogas.

They are, however, relatively clean. Cars that run on hydrogen derived from natural gas emit 55% to 65% less carbon than gasoline-powered ones, because they’re more efficient; they also don’t spew carcinogens or smog-forming compounds. Battery-electric and fuel-cell cars emit about the same amount of greenhouse gases per mile when natural gas is used to produce electricity or hydrogen, according to a February report from the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Currently, an electric car is probably cheaper to operate than a fuel-cell vehicle with comparable range. Based on one estimate—though it may be dated—a fuel-cell car will cost three or four times as much per mile. But that could come down. While the big car companies’ interest in electric cars has been fickle, following equally fickle mandates from state and federal regulators, a handful of car companies have stayed the course on fuel cells, steadily improving the technology over the years.

The road to the future begins in Los Angeles

The epicenter of fuel-cell technology in the US lies a few miles from the Los Angeles International Airport. That’s where Honda and Toyota maintain their US headquarters (Hyundai’s HQ is in neighboring Orange County.) More than a decade before California enacted its groundbreaking 2006 climate-change law, which mandated big reductions in carbon emissions, the state had decreed that the major automakers meet targets for selling emission-free vehicles to combat air pollution. That has made smoggy southern California the test bed for both electric and hydrogen-fueled cars.

Toyota, for instance, began its fuel cell program in 1992. Despite building perhaps the most successful hybrid electric car, the Prius, which paved the way for consumers to accept pure electric vehicles, Toyota has long been skeptical of electrics. “We see a way forward for commercializing fuel cells,” says Scott. “That’s why were bullish on this. We’re still having a hard time seeing costs come down for batteries.”

Daniel Sperling, the director of the Institute of Transportation Studies at the University of California, Davis, recently visited Toyota’s fuel-cell research and development labs in Japan. “They have a massive investment in fuel cell technology and clearly see a path to the mass market,” he told Quartz. “I think they’ve gotten to the point where the costs are low enough that they won’t lose too much money.”

How a $1 million car became a $50,000 car

These advances have been a long time in coming. Toyota introduced its first prototype fuel cell car in 1996. Eleven years later it modified a Highlander SUV to run on hydrogen. These early fuel cells were hand-built, hence the million-dollar Mercedes I drove. Toyota’s Highlander reportedly cost a similar amount. But in January of this year, when executives unveiled the FCV, a sleek prototype of a car due to be released in 2015, they said they had reduced costs by 95%.

How? For one thing, the cost of electric power trains and motors has plummeted, thanks to the mass production of the Prius and other hybrids. Fuel cell systems have also gotten more advanced. Scott says Toyota’s latest fuel cells are more efficient, more powerful, and use less platinum, the priciest of precious metals.

Honda, similarly, built its first hydrogen prototype, called the FCX, in 1999 and delivered five of the cars to the city of Los Angeles in 2002. Six years later, Honda began leasing the FCX Clarity for $600 a month, hydrogen included. There are about two dozen of the claret-hued cars currently on the road in the LA area. Like Toyota, Honda is launching a new model next year; the name is as yet undecided.

Now, at Honda’s sprawling US headquarters in Torrance, California, Steve Ellis, the company’s manager for fuel cell marketing, notes that the fuel-cell stack for next year’s car will be 33% smaller than the previous version. The energy density has jumped 60%, meaning the fuel cell generates more power at a lower price. “We’re not nibbling at the edges here,” says Ellis. “There’s leaps in technology advancement and cost reduction.”

A worthy competitor to electric cars

I took a spin in Honda’s FCX Clarity to get a taste of what next year will bring. It’s a sleek, technology-packed four-seat sedan, and you can have any color you want as long as it’s Star Garnet Metallic. The 2013 model is a copy of the original introduced five years earlier, but under the hood the fuel cell has been tweaked over time to improve performance. While the Clarity does not rival the Tesla Model S in sheer style and whiz-bang technology—there’s no 17-inch iPad-like touch screen to control the car—it’s decked out with luxury touches and gizmos like a collision avoidance system.

Like most electric cars, the Clarity runs silent. It accelerates swiftly through the boulevards surrounding Honda’s corporate campus and holds its own on LA freeways. There’s one big difference: After I pull into a hydrogen fuel station near the Honda campus and top off the tank, The range indicator reads 240 miles. The next-generation car will travel more than 300 miles.

A Nissan Leaf or Ford Focus Electric, by contrast, goes only about 75 miles on a charge. An entry-level, $63,570 Tesla Model S has a range of 208 miles, while the $75,070 version goes 265 miles. It takes four hours to fully charge the high-range Model S using a fast home charger. On a road trip, drivers can add 170 miles of range in 30 minutes at Tesla’s Supercharger stations. Clarity’s refuel time? Just a few minutes. I pop open the fuel door, plug in the fire-hose-like apparatus, and lock it into place. (A new pump design will reduce refueling time to fewer than three minutes.) It’s not too different from fueling a gasoline vehicle. I drive off without a twinge of range anxiety.

No automaker will reveal the production cost of its hydrogen cars, but analysts peg it at between $50,000 and $100,000. Gil Castillo, senior group manager of advanced vehicles for Hyundai in California, says costs have dropped 70% since the Korean company began working on fuel cells in the late 1990s. “I wouldn’t say that they’re at a price where they would equal a regular mid-sized sedan but they’re possibly up there with higher-end electric vehicles,” he told Quartz. Hyundai has announced it is leasing its hydrogen SUV for $499 a month, with fuel thrown in for free. Honda and Toyota haven’t yet announced pricing.

The cars are pricey but the fuel is cheap… probably

That the Hyundai lease includes free fuel indicates just how unsettled the economics of hydrogen remain. With so few hydrogen cars currently on the road, companies are reluctant to build lots of fueling stations, which can cost more than $1.5 million apiece. But automakers don’t want to put cars in showrooms until they know drivers can find a neighborhood hydrogen gas station. “The oil industry does not see a reward for being an early mover and has been unwilling to make big investments in hydrogen stations,” says Sperling.

The problem isn’t necessarily supply. Hydrogen is used in oil refining, food production and other industrial processes, and supplies are plentiful in California. The question is how to transport it and what to charge for a kilogram of compressed gas to make a profit. One model is the prototype Shell hydrogen station in Torrance, which resembles a typical suburban gasoline station, minus the mini-mart selling junk food. A pipeline delivers the hydrogen from a nearby production facility and drivers punch in a code to access the pumps. As I filled up the Honda Clarity, another driver was pumping hydrogen into a fuel-cell version of a Chevrolet Equinox SUV.

But not everyone lives near an oil refinery, and building new pipelines isn’t cheap. At a station in Burbank, hydrogen is produced onsite by extracting it from natural gas. Greener yet, a station in Santa Monica creates its own hydrogen with an electrolyzer that uses an electrical current to split water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen. (The station buys renewable energy from a local utility.) And a station in Orange County produces renewable hydrogen out of methane gas from a wastewater treatment plant.

California’s solution to the hydrogen chicken-and-egg conundrum? Cash. State funding will pay up to 70% of the capital costs of building the first 100 fuel stations, and subsidize operating and maintenance costs. “That has given station developers more confidence that they can make this investment and not lose their shirts,” says Dunwoody of the California Fuel Cell Partnership. “After we get to 100 stations, there will be enough investment in the market.” Or least that’s the hope.

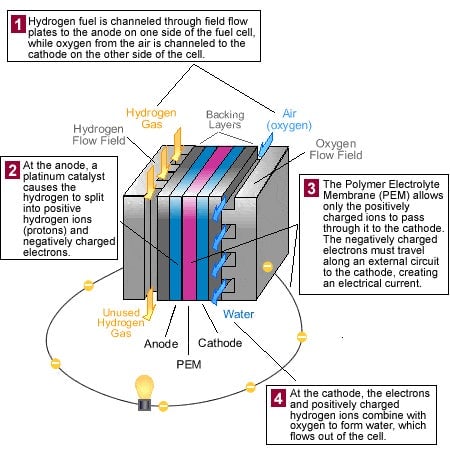

California’s on-ramp to the hydrogen highway

A 2012 report from the organization estimates that 100 fueling stations will support more than 53,000 hydrogen vehicles. A network of 68 stations by the end of 2015, in the right places, would be enough to get the market to the tipping point of being commercially viable, the report says. Most will probably be installed at conventional gas stations.

Daniel Poppe, vice president of Hydrogen Frontier, a southern California company that builds and operates fueling stations, says the state funding will keep the market going until a critical mass of vehicles are on the road. “If we see a large number of cars, in the thousands not hundreds, then there will be a huge opportunity for all types of businesses to support the commercialization of hydrogen as a mainstream transportation fuel,” he told Quartz in an email.

California is taking a much more planned approach to hydrogen fueling than it did to electric-car charging. For electrics, cities and businesses have set up charging stations willy-nilly in the hope that if they build them drivers will come. The state, on the other hand, is creating strategic clusters of hydrogen fueling stations in regions home to affluent, environmentally-conscious early adopters. In other words, the same places where a Tesla Model S is a common sight—Berkeley, San Francisco, Silicon Valley, Santa Monica, west Los Angeles and coastal Orange County.

Given the hydrogen cars’ range, the state also estimates that a few “connector” stations located along major highways will allow drivers to travel from Los Angeles to San Francisco and popular destinations like Lake Tahoe, Palm Springs and the Napa wine country. That, as it happens, is a strategy pioneered by Tesla, which is building a national network of Superchargers to allow Model S owners to drive cross-country for free.

Can the big automakers out-Tesla Tesla?

The party line from green car proponents is that battery electric and fuel-cell technologies are complementary, filling different niches. The hard truth, though, is that Tesla may well end up being the biggest rival to hydrogen cars.

In February, Tesla revealed plans to build the world’s largest lithium-ion battery plant—a “gigafactory”—to drive down costs, so its next car, set to debut in 2017, can be cheap enough for the mass market. According to Tesla’s estimates, the gigafactory would allow the company to make 500,000 cars a year. (This year Tesla expects to build only 35,000.)

While Honda, Hyundai and Toyota are not disclosing sales targets, they say they expect only a few thousand cars to be sold or leased at first. “It’s completely unrealistic that everyone will be driving a fuel cell in a couple of years,” says Hyundai’s Castillo, noting the company will only make 300 hydrogen cars a year between in 2014 and 2015.

But the major automakers have the capacity to make far more cars than Tesla, which should further reduce fuel-cell costs. (They’re also cooperating with each other; Honda and General Motors are hooking up on R&D, and Toyota has a similar deal with BMW.) And even if hydrogen remains more expensive, mile for mile, than electricity, there’s still a trade-off in fueling time—three to five minutes for a hydrogen car versus hours for a battery-electric vehicle.

The solar-powered hydrogen car

While both electric and fuel-cell cars still rely on fossil fuels to generate their sources of power, both types of technology could also spur renewable energy production. Tesla’s battery packs already are being used to store electricity from rooftop solar panel arrays and its gigafactory would produce gigawatts of energy storage that could upend the utility industry.

In California, state law requires that a third of hydrogen used for transportation come from renewable sources if the producer received government funding. Once there are 10,000 fuel cell cars on the road, that rule kicks in for all hydrogen producers. “As we get to larger and larger volumes of hydrogen, California must look at more large-scale renewable energy production,” says Dunwoody.

Or small-scale. At Honda’s R&D campus, I drive the Clarity up to a gate that opens to reveal a prototype of a solar-powered hydrogen fueling station for the home (see picture above). The electrolyzer is powered by a 5-kilowatt photovoltaic panel array and can produce 30 miles’ worth of hydrogen overnight in your garage, from water. (Honda is still working to bring down the cost of home-brew hydrogen.) The gas can also be used to power residential fuel cells like those being developed by power giant NRG Energy.

No utility or oil company needed. Just drivers.