European companies are walking a political tightrope to do business in China

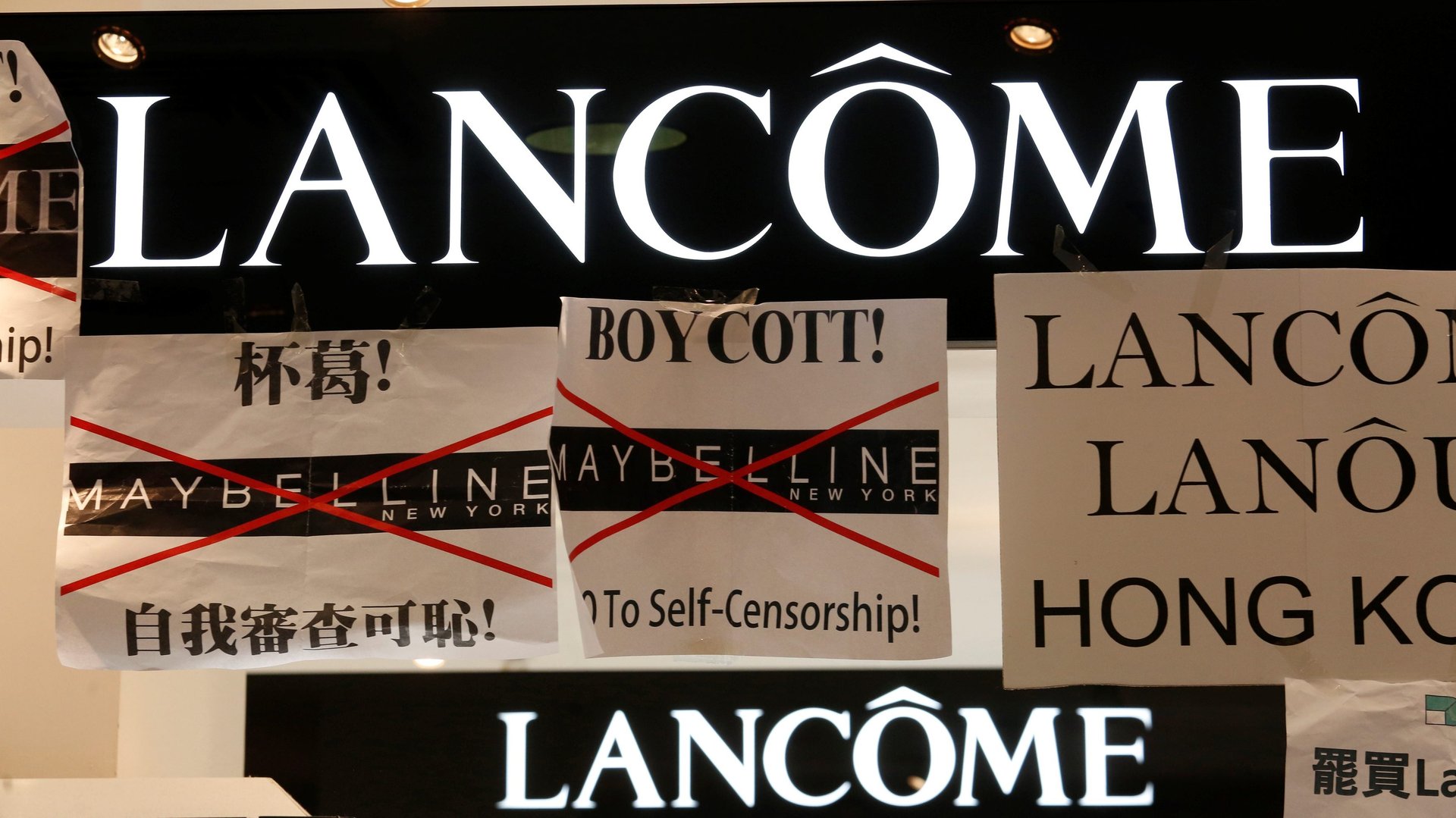

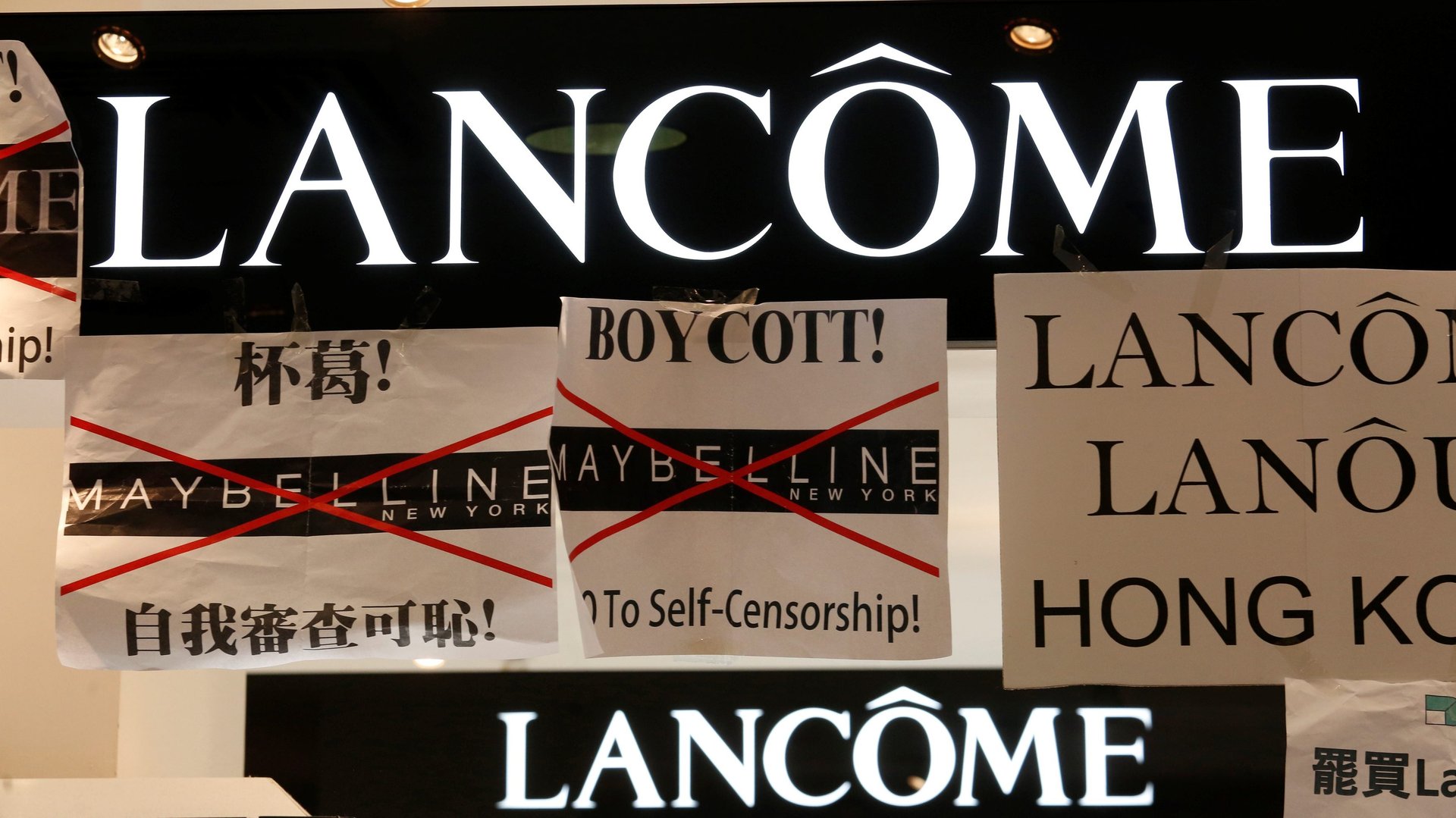

In 2016, French cosmetics brand Lancôme organized a free promotional concert in Hong Kong. A few days later, confronted with mass online criticism, they canceled it: The artist meant to perform, pop singer Denise Ho, had met with the Dalai Lama and campaigned for democracy in Hong Kong, two causes antithetical to Beijing’s One China principle. In the face of calls for a boycott, the luxury brand backed down.

In 2016, French cosmetics brand Lancôme organized a free promotional concert in Hong Kong. A few days later, confronted with mass online criticism, they canceled it: The artist meant to perform, pop singer Denise Ho, had met with the Dalai Lama and campaigned for democracy in Hong Kong, two causes antithetical to Beijing’s One China principle. In the face of calls for a boycott, the luxury brand backed down.

The incident is illustrative of a broader problem that foreign companies face when doing business in China: The need to bend to Beijing’s political will in order to retain market access. Other recent examples include German car manufacturer Daimler, which apologized in 2018 after its Mercedes-Benz brand posted an ad on Instagram that featured a quote from the Dalai Lama, whom Beijing considers a separatist. That same year, Gap pulled a t-shirt from its shelves in Canada because it featured a map of China that didn’t include Taiwan. (China claims Taiwan as its own, though the ruling Communist Party has never had sovereign control over the territory.)

In an increasingly tense geopolitical environment—with a massive economic slowdown tied to the spread of a virus that appears to have originated in China, Beijing and Washington engaged in a trade war, and protests in Hong Kong—the problem is getting worse. According to a recent survey by the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China, 43% of European companies in China believe that the business environment has become more political over the last year.

Two in five companies say that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is present in their operations. That’s not entirely surprising, since most businesses in China have party units in their ranks, and often in their leadership. But foreign companies say they are increasingly pressured to give those affiliated with the party control over day-to-day operations and major investment decisions. European businesses surveyed by the Chamber report that the presence of the CCP in their ranks gives them “access to government contacts,” “guaranteed approval in administrative matters,” and “early access to regulatory/administrative information.”

In the survey, European companies report that the government is a major source of external pressure, as is Chinese media. Concretely, 24% of respondents reported feeling pressure from the Chinese government to carry out certain political actions.

The survey’s findings are in line with a report published this month by the US-based Human Rights Foundation (pdf), which found that “since the 2019 Hong Kong protests, the CCP has clearly signaled that foreign companies operating in China must help advance the its agenda, or face expulsion from the Chinese market.”

The politicization of business is one of many obstacles European companies report facing in China, in addition to unfair competition from state-owned enterprises, forced technology transfers, and opaque licensing processes. Chinese authorities have promised to accelerate reforms. But, according to the European Chamber, these reforms—which it calls a “grab-bag of incremental improvements”—have largely failed to materialize. As China’s economy struggles to rebound from Covid-19, the business environment will likely get worse for foreign companies.

David Baverez, a French investor based in Hong Kong, says that these obstacles, far from being a glitch in the system, are one of its features. He argues that an increasingly nationalistic Chinese government wants foreign companies to shoulder the burden of the economic downturn. “The cake is getting smaller, so we have to make them leave, and we’ll replace them with Chinese companies,” is how Baverez describes Beijing’s thinking.

“If there is a slowdown in the Chinese economy, you don’t want to let foreigners make money,” adds Jean-François di Meglio, president of the Paris-based research group Asia Center, and a former executive for BNP Paribas in China.

However, foreign companies have some leverage. China needs to find stable employment for those who lost their jobs due to the pandemic. Officials want to create 9 million new jobs this year, and they will need the private sector to meet that goal.

Although European companies in China appear to be wary of the increasingly political dynamics of doing business there, half of the respondents of the European Chamber’s survey plan to expand their China operations, and only 11% said they were considering shifting current or planned investments in China to other markets. That, says di Meglio, is why “if I was a Chinese leader, and I read this report, I would keep doing exactly what I was doing.”