Curaleaf, the US’s biggest cannabis company, with a market capitalization of about $3.2 billion, just keeps getting bigger. The Wakefield, Massachusetts-based operator of grow houses, dispensaries, and brands turning out tinctures, vapes, edibles, topicals, and flower (as the industry refers to dried cannabis) has been steadily acquiring other cannabis companies in an effort to become, as CEO Joe Lusardi puts it, “the first true national cannabis brand with the widest distribution in the country.”

Curaleaf began in 2010 as PalliaTech, a medical cannabis company. It raised tens of millions from a Russian investment firm between 2013 and 2015 led by Boris Jordan, who made a fortune in data centers and energy in Russia after the fall of the Soviet Union, and is now chair of Curaleaf’s board. Curaleaf went public in late 2018 on the Canadian Securities Exchange, and the company’s merger last month with Grassroots Cannabis expands its footprint to include 23 of the 33 US states where cannabis is legal. It also gives the company licenses for 135 dispensaries and more than 1.5 million square feet of growing capacity.

Just before that deal closed, Lusardi talked to Quartz about the company’s growth strategy, what makes him optimistic about the next 36 months, and why he looks to the alcohol industry after prohibition for guidance amidst the pandemic. This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Quartz: Does 2020 feel like an inflection point for the cannabis industry?

Joe Lusardi: I’ve been in the industry for 10 years now. I would say it’s more of a gradual acceptance that cannabis is mainstream. A lot of people are using it for both medicinal benefits and for health reasons. It’s gradual, but I’m very optimistic. We now have 33 states and counting in the medical programs, and 11 states with adult use [also known as recreational] programs—and a lot more coming up here in the November election.

I think this fall could potentially be a very big catalyst for cannabis reforms at the federal level. I’m absolutely certain that you’ll see more states vote for both medical programs and adult-use programs. I think the next 36 months is going to be a very interesting, exciting time for this nascent industry.

How about being deemed essential businesses in the early days of the coronavirus pandemic—did that feel significant?

Without a doubt. I’ve been in this industry for a decade and fighting for acceptance all along the way. For the administration to recognize that these products were essential—that, effectively, people can’t live their lives without them—was a massive validation. No question of how important cannabis is in people’s lives.

As you look to the future of the cannabis industry—and being that you’re one of the companies that is designing it in a sense—are there other industries you think have done it right when it comes to marrying good policy and business tactics to grow into a healthy sector?

This is a whole different and new paradigm. It’s hard to make any perfect analogies. Certainly, you could look at alcohol at the end of the prohibition. You can look at retail companies like Starbucks and Apple. Or you can look at a lot of consumer product goods companies, and how they build brands.

But cannabis is its own thing. It’s a product that spans wellness and adult use applications. It’s sold retail and wholesale. We look to [other] industries for sure, but there’s no perfect sort of example that we can draw on. We’re developing a lot of it as we go. It’s a lot of white space, which is frankly very exciting.

Can you elaborate on the post-prohibition era of alcohol, if there are interesting lessons or cautionary tales there that you look to?

It’s becoming even more analogous because at the end of the depression, people were looking for revenue sources, much like you’ll see coming out of this pandemic. It’s very clear that many states are now going to have tremendous budget shortfalls. I think Americans are also becoming less willing to continue to lock up people for nonviolent marijuana crimes. I think it’s pretty interesting that you’re going to see people look at the cannabis industry as a job creator, and also as a potential source of tax revenue.

The other thing we look at the alcohol industry for is how they build brands and how they handle distribution. As you know, right now cannabis can’t cross state lines, and so we’re building distribution market-by-market, much like alcohol did. So what Curaleaf is doing is trying to create a national brand on the back of what will be a 24-state platform after we close Grassroots next week, much like the alcohol companies built brand across their platforms. That’s what we’re focused on, and I think it’s probably as good as an example you can look at, at how to create brand in a new industry.

My understanding of that post-prohibition era was that in order to keep alcohol companies from getting too powerful, regulators wouldn’t let the same businesses that produce alcohol sell it to consumers. If you owned a bar, you couldn’t also make the booze. Do you foresee something like that happening with cannabis? Is that something that you think about?

For sure. What’s interesting is that already each state has its own regulatory regime with its own set of laws. And most of the states in the country have prohibitions against one company getting too big. For example, you can only own so many distribution points, or you can only own one license. I think states already have rules and regulations to keep any company from being too big. But what we’re trying to do is a little bit different, in that we’re trying to create a national brand—the first of its kind—by having distribution across all the legal states that we can, as fast as we can. I think that’s what will make us a leader in the space: I believe we will create the first true national cannabis brand with the widest distribution in the country.

And Curaleaf is really the retail brand for the dispensaries?

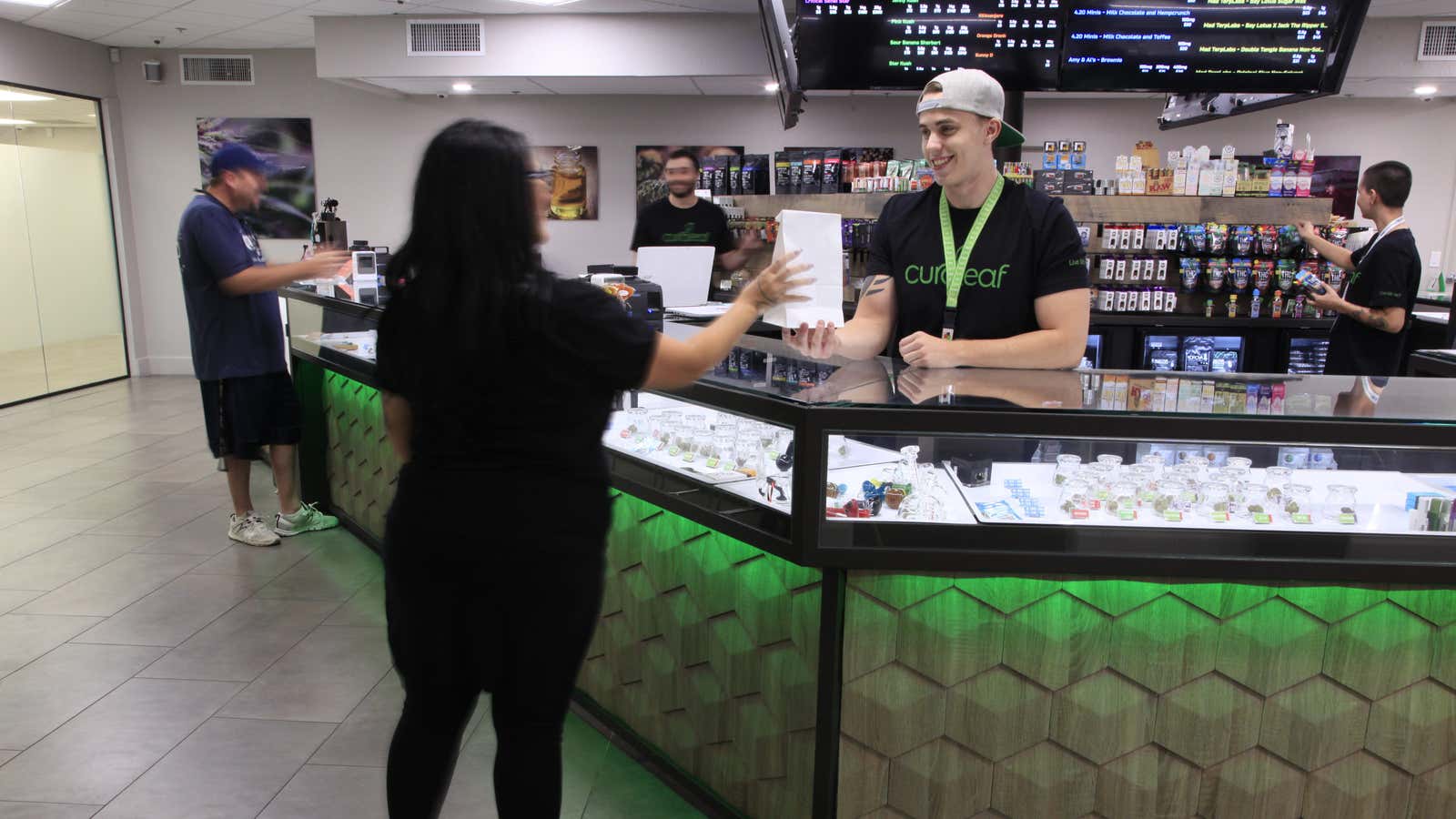

If you think about Curaleaf, it’s really a two-brand architecture. Curaleaf is our medical wellness brand. It is also the name on our stores; it’s also the retail brand. Much like Apple is the retail brand that sells Apple products. That’s kind of how we think about Curaleaf: the retail stores are an extension of our brand, where people come and learn about Curaleaf products, and how they can use those products to live their lives better.

We acquired Select earlier this year, which is an adult-use west coast brand. And we are now going to carry Select across the country, and we believe that will be the first—or it will be the first national adult-use cannabis brand. It’s moving so fast. I think it’s already in 11 States. When we bought it, it was in four. Our goal is to have Select be in 23 states by early next year. And no other brand in the industry will look like that. So Select is our wholesale adult-use brand, and we’re really excited about building to create national recognition.

Can you describe Curaleaf’s acquisition strategy? Is it more about geography? Product range? Brands for different demographics? Licenses?

It’s mostly about geography, which, frankly, means licenses. We acquired our way into many markets like Nevada, Arizona, Maryland, to name a few, Connecticut, Florida. And then we won [licenses] and we built businesses in Massachusetts, Maine, New Jersey, New York. And so we’ve definitely built the business both through greenfield and through acquisitions, largely to build footprint.

But importantly, we’re building footprint in the most highly populous—and what we consider to be the best—supply-demand dynamic markets in the country. For example, we haven’t put a heavy emphasis yet on markets like California, Oregon, Washington, or Michigan, because frankly, they’re very poorly regulated. There’s too much black market, there are too many operators. And so the supply-demand dynamics do not look attractive. We’re focusing on markets where there’s a more rational regulatory regime in place. That really for the most part means we are focused on markets like Arizona and Nevada, and east—including Illinois, the midwest and the east coast—that have done a more thoughtful, more controlled rollout of the regulation.

What state do you think has been the best organized when it comes to this? I’m in California where there’s a lot of talk about what a catastrophe it’s been. Where has it worked really well from a business perspective?

I think there’s a lot of good examples of that. Nevada did a terrific job of moving from medical [use] right into adult-use. Illinois, although it’s supply constrained, moved very quickly and has done by all accounts, a very good job with their regulations. So there are a number of examples of states that have gone from well-regulated medical programs, and were able to adopt adult-use programs. In this next election season, you’re likely going to see New Jersey and Arizona pass adult-use laws. Both of those markets are well-regulated and performing well from an industry perspective. And I think they’ll do a good job getting adult-use programs enacted.

As we’re talking about policy and election season, I’m curious about lobbying. Where you have seen the most effective inroads from lobbying? What kind of progress do you feel like you’re making?

We are very active in that regard, both at the federal and the state level. We’ve got a really strong government relations team that has developed very intimate relationships with regulators and legislators at the state level. And I think they’ve done a very good job of making sure that we have rational, good public policy and the programs operate smoothly. To be candid, at the federal level we’ve been very disappointed with how slow things have gone. We don’t view cannabis as a partisan issue. We think we have support on both sides of the aisle, but we’ve been disappointed with the lack of movement in the Senate on any legislation that’s come out of the House. And so that’s probably our biggest disappointment.

What about the biggest victory?

I think the Illinois law is a terrific law. Not only did it pass through the legislature—which is rare—but it also has a very strong social justice component to it. I think that law is very reflective of where the country wants to go on cannabis, which is that Americans, by a large margin, now support cannabis for both adult use and medical. They also do not support the idea of incarcerating people—primarily of color—for nonviolent marijuana crimes. And there’s also a recognition that the war on drugs has disproportionately affected those communities. And so there should be a seat at the table for social justice applicants. I think Illinois is a very good example, maybe the best in the country, of a law that makes sense for where the country is on this topic.

What about where you are as a company on this topic? Curaleaf’s board is 100% male, without female, Black, or Latino representation. Can you talk about how you think about that responsibility and whether you think about a board that’s more reflective of the market that you serve?

We recognize that, and given the moment in time, we can always do better and we will do better. We’ve got a strong corporate social responsibility arm led by Khadijah Tribble. We’re going to be working on that as a company. We’re four years old. We’re a new company, but we recognize that we can and will do better in that regard.

What you’ve described for Curaleaf is a massive national expansion. Do you think cannabis will eventually be a global business, where we’re importing and exporting cannabis from overseas?

That’s a 100% certainty. There’s absolutely no question. Over the next five to 10 years, this will be an international business. Cannabis already is being imported and exported in Europe, Israel, and South America. The United States is so out of step with the way human beings around the globe think about cannabis. I am optimistic that it will change because frankly, I don’t see any other way this can end. It’s just become so accepted, and the government needs to get in line with where the people are on this topic.

What might that global industry look like? Coffee, where it’s grown one place and shipped another? Beer, where there are local facilities brewing for international brands, or something else entirely?

I think it will be both. I think you’ll see some cannabis that’s used simply as feedstock for manufactured products, that could be grown in South America or the place with the lowest possible input costs. But I also think flower will be very much like wine, and there will be sort of boutique grows and brands that are known by regions. I think it’s going to be a very diverse industry with a lot of people operating in it, and a lot of different value propositions. It’s going to be its own unique paradigm. I don’t think it will look like any other industry we have today. I think it will have some parallels to beer and alcohol, some parallels to pharmaceuticals, and some parallels to consumer packaged goods. But it will be its own thing. There’s no question.

How does federal cannabis prohibition affect your business from a financial perspective, like going public on the Canadian stock exchange and taking a good deal of foreign investment?

It adds a huge amount of frictional costs to our business. We can’t have national banking relationships, we can’t use credit cards. We spend a lot of money in security moving cash around. Our cost of capital is significantly higher than it should be because traditional lenders can’t lend to cannabis. Most investors can’t invest in our stock right now because of the federal prohibition. It puts a lot of limitations on how far we can go.

Do you have any concern about competition from the Canadian companies if and when legalization does open up?

The way we think about it right now is our biggest competitor is the black market. You know, 90% of cannabis is still consumed in the black market. Our job is to create legal, regulated, taxed cannabis. I think we’ll be very successful with that. And if we do that, the industry is big enough for many companies to thrive and be successful, not just Curaleaf.