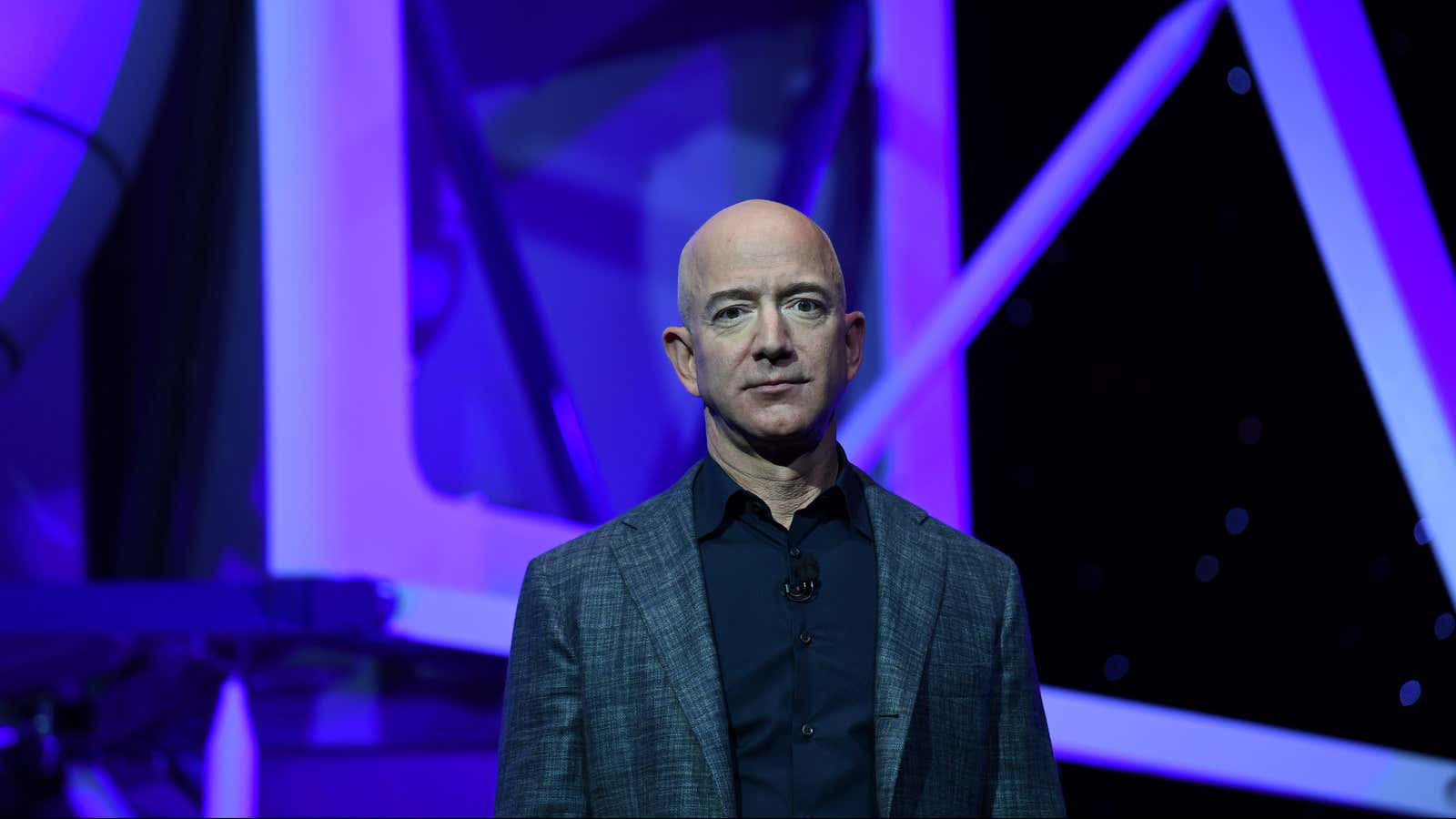

On Wednesday, the US House Judiciary Committee will hear testimony from four titans of tech: Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, Google’s Sundar Pichai, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, and Apple’s Tim Cook. The event will cap off the committee’s year-long investigation into whether Congress should reanimate antitrust laws born in the Gilded Age and apply them to the barons of the 21st century digital economy.

Under the reigning interpretation of American antitrust law, the executives who testify this week have little to fear from lawmakers or regulators. In recent years, courts have adopted consumer prices as the sole standard to judge whether a market is too concentrated: As long as prices stay low, companies stay out of trouble.

Stacy Mitchell is among a new group of scholars who argue this interpretation of monopoly law must change. She studies the impact of Amazon’s growth on competitors and consumers and co-directs the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, which urges lawmakers to curb corporate power. The organization submitted a list of policy recommendations to the congressional subcommittee on antitrust reform in May, arguing that many of the same laws that applied to railroad bosses of the early 20th century can be used to rein in Amazon and its peers.

The following conversation with Mitchell has been edited for clarity and length.

Quartz: How has the standard interpretation of antitrust laws changed since they were passed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries?

The original thinking behind antitrust laws was that companies that amassed monopoly power could use that power in abusive ways, both to harm consumers, but also to harm producers. There was a sense that it was important to protect Americans’ rights to operate as free and independent citizens when they were working or running a business.

That’s how antitrust laws operated up until the 1980s. Starting in the ’70s, there was a school of thought associated with the University of Chicago that said the only purpose of antitrust should be efficiency, and we should just try to maximize output in the economy. Embedded within that way of thinking was the idea that bigger companies are inherently more efficient. Over time, antitrust actually started working in service of increasing concentration.

What effect has that had on the growth of tech companies like Amazon, Google, Facebook, and Apple?

The tech companies have very cleverly structured their business models in ways that their services are generally free or low cost to consumers. That design has allowed them in the current antitrust environment to amass an extraordinary amount of market power. They have exercised that market power against their suppliers, the companies that depend on platforms, and other competitors, so they are effectively squeezing Americans as producers of value rather than consumers. Antitrust laws in their current conceptualization have been completely flat-footed.

You’ve argued that “Amazon Doesn’t Just Want to Dominate the Market—It Wants to Become the Market.” What did you mean and why is that an issue?

More and more of the consumer goods trade is happening not in an open market, but in a private marketplace owned by Amazon. More than half of the time we buy online, we start by searching on Amazon. The alternatives are anemic: Walmart and eBay are tiny compared to Amazon in terms of traffic.

So if you want to reach consumers online, you can give up half the market out of the gate or you can submit to Amazon. If you submit, they get to levy all these fees on sellers—referral fees, fulfillment fees, making sellers buy ads, or buy brand registry to protect against counterfeits, and so on. And of course it’s not just the marketplace but also AWS, which carries much of the world’s internet traffic, or Alexa, which is intermediating how we access web content as we move to smart devices.

This is effectively a way in which Amazon is taxing the trade of a growing share of the economy. Amazon has a position in which it can take something in exchange for being the middleman in a transaction. And at the same time it’s doing this, it’s actively competing against the companies that use its infrastructure [or seek its venture capital funding]. This is a market in which one entity has a godlike view of everything that is happening, and everyone else is in the dark.

Do existing antitrust laws address that?

In many respects tech companies are new and different, but they have antecedents in history. One prominent example is the railroads. When they came along, powerful industrialists including John Rockefeller of Standard Oil gained control of key rail lines, and they used that control to disadvantage their competitors in those industries. So for example, Rockefeller cut deals to allow his oil to pass but restrict other oil companies from accessing those rail lines.

This is similar to what we see with Amazon and other tech platforms.

The approach Congress took with railroads was to pass a law in 1906 that said you can’t operate a rail line and, at the same time, have a financial interest in businesses that ride on the rails. It also said that the rails are a common carrier, meaning that you have to treat all comers equally and you can’t discriminate in favor of some over others. You could apply similar rules to Amazon.

What would that look like?

You would need some sort of public oversight. This could be vested in an existing agency like the Federal Trade Commission or perhaps a new agency that would have oversight over the terms and operation of the marketplace and would have a role in being able to field complaints.

Common carriage rules don’t work unless they go hand in hand with breakups. Given Amazon’s overwhelming interest in self-dealing combined with the huge number of transactions happening on its platform, the enormous number of sellers, and all of the opacity of its algorithms, I think it’s very difficult to imagine a scenario in which Amazon still has its own retail and manufacturing division. It will almost undoubtedly find ways to tip the scales in its own favor that are hard to detect or hard to police, and that’s I think why we have to remove that fundamental conflict of interest.

When comparing this antitrust reckoning to the one around railroads, what sticks out to you?

While looking back at the history of this country’s anti-monopoly tradition, I’ve been really struck by how different the public conversation around monopoly policy used to be. If you go back and look at newspapers from the middle decades of the 20th century, the word “monopoly” shows up all time. It was on the front pages. It was a regular part of the discussion in the way that health care policy and minimum wage are part of our ongoing public discussion today. Antitrust used to be that way, and it has just totally disappeared from the public sphere.

Most Americans now really only have a vague idea of what antitrust is about, and they don’t really feel comfortable talking about it. And that’s part of how these companies have been able to amass all this power and how we’ve been left at a loss to know what to do about it. Part of the reason that Americans used to be more engaged with antitrust is that the agencies themselves used to operate in a more open way—and if we did that today, that could be a really important step toward building political support for strengthening antitrust.