Opioid abuse disorder has typically been characterized as a white and rural issue. But non-white people suffer from it too, even if they aren’t the main focus of public attention: In 2018, of the 21.3 million Americans with substance abuse disorders, 2.3 million were Black, and 3.3 million were Hispanic.

While all groups abuse opioids, their access to treatment is vastly different. Both Black and Hispanic people suffering from substance abuse are far less likely to receive mental health treatment—through medication as well as counseling—for substance abuse than the overall US population. The same is true of other minorities, too, although the overall volumes of people affected are much smaller.

Opioid-related deaths among whites have fallen since 2017, as tackling the epidemic became a public health priority. But deaths among Black and Hispanic people continued to climb over the same timeframe.

“I think the opioid crisis got a lot of attention because it was recognized as a white problem, but communities of color have been impacted by it the whole time,” says Kenneth Morford, an assistant professor of medicine at Yale who specializes in opioid addiction treatment in his clinical practice.

This discrepancy is putting Black and Hispanics at especially high risks of overdose deaths during Covid-19, according to initial reports from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), especially as initial reports suggest a significant spikes in overdoses since the beginning of the pandemic.

One of the reasons is these groups tend to be in worse socio-economic circumstances and feeling the financial effects of the epidemic more closely—and economic distress is a key risk factor in substance abuse disorder. Further, members of these communities are often frontline workers, which exposes them to higher risks of contracting coronavirus—and higher exposure to the distress of serious health effects or even death.

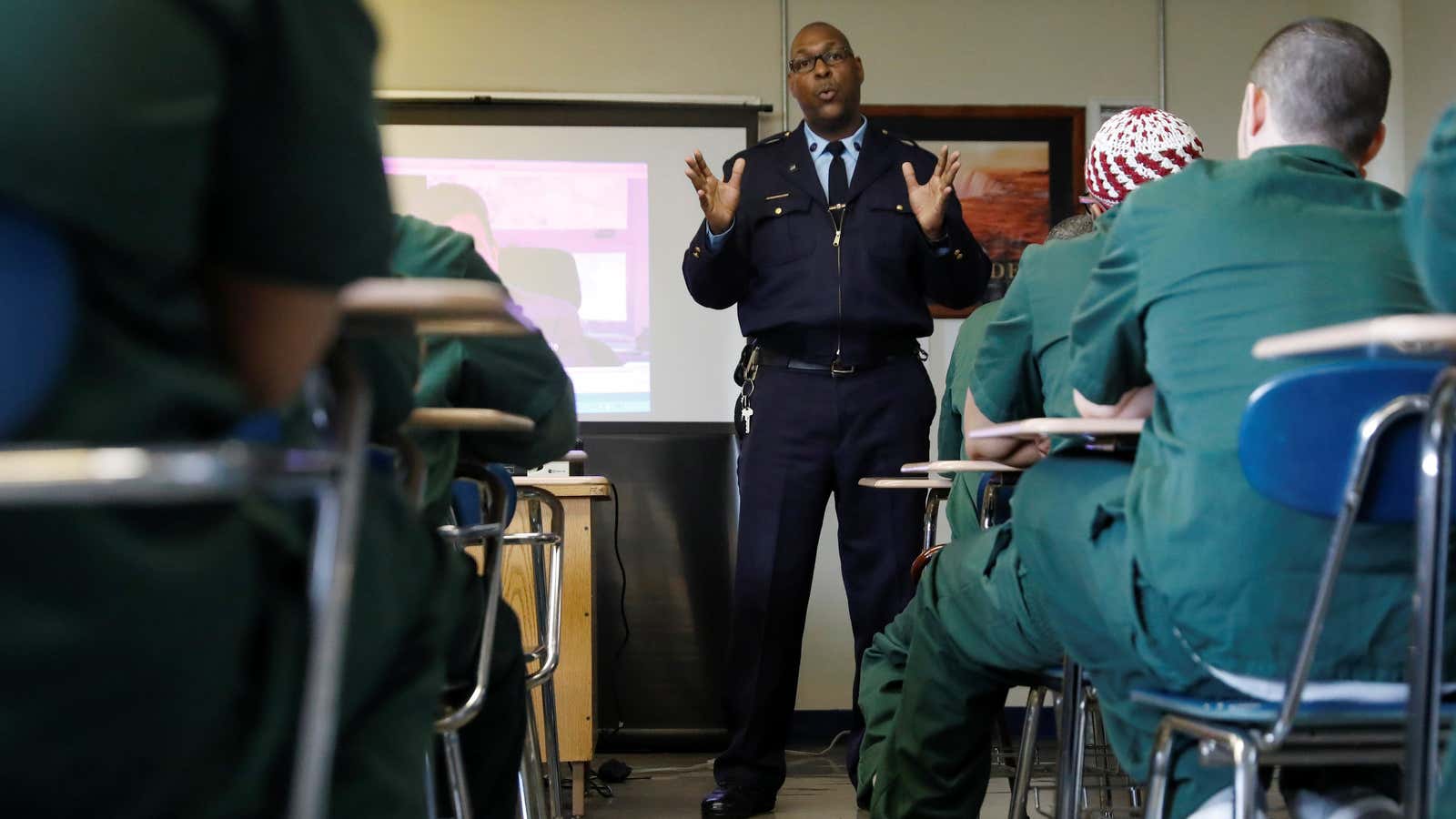

An additional element of risk, especially for the Black population, is the effect of Covid-19 in prisons, where they are overrepresented. This is not just because outbreaks in jails have been devastating, but because the pandemic has significantly disrupted the opioid treatment routine within the jail. For instance, clinicians haven’t been able to continue their routine in-person visits, and support groups have been paused. As Morford noted, a large segment of Black opioid addiction patients who access treatment do so through the jail system.

Further, the prisoners who were released in order to reduce the jail population often weren’t able to get immediate support for opioid addiction treatment at a time when they would be especially in need of it. “There is a known increase in mortality and overdose when people leave jail or prison,” says Morford. Someone with a substance use disorder who hadn’t been using drugs in jail would easily have lower tolerance, and be at higher risk of overdose.