Coronavirus has highlighted the racism running through US healthcare, as Black and Latino Americans die of Covid-19 at disproportionately higher rates than white people. In an effort to counter those disparities, government officials are now grappling with whether to make race an explicit feature of plans to distribute a potential vaccine.

On Sept. 1, a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) panel published a draft of plans for who within the US should get a vaccine first, one of several potential guidelines being developed. The early plan does not explicitly prioritize people based on race, but incorporates several measures to would help accomplish that result indirectly.

“This virus doesn’t understand skin color, but it understands vulnerabilities,” said Bill Foege, co-chair of the NASEM panel and former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The panel prioritized several risk factors that often predominantly affect communities of color, he said—such as working in high risk jobs including transport and service industries, comorbidities like diabetes and obesity, and overcrowded housing—rather than race itself.

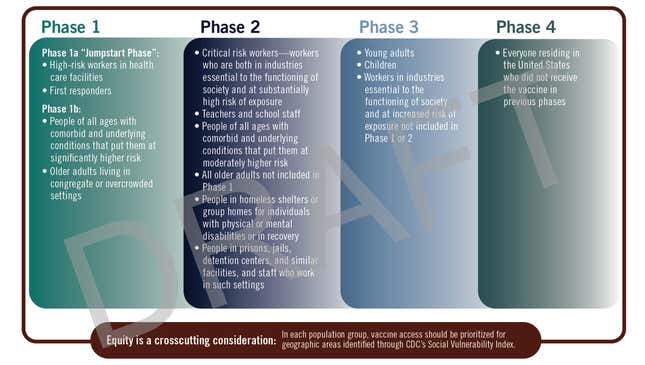

Overall, the committee considered risk of infection, risk of death, potential negative societal impact, and risk of transmitting the infection to others in establishing its guidelines. Under this draft plan, as expected, the first to get a vaccine would be high risk healthcare workers, followed by those with severe comorbidities and older people living in crowded environments.

The second phase would focus on high risk essential workers, such as those in delivery and transport, teachers, those in homeless shelters and prisons, and older people who have yet to receive a vaccine. The third distributes vaccines to young adults, children, and any other workers in essential industries. And finally, phase four would give a vaccine to anyone who hasn’t got one yet.

At a public hearing held Tuesday (Sept. 2), Foege emphasized that the draft is subject to revisions, and several speakers advocated for amending the priorities so they more explicitly account for racial disparities in risk. Racism has contributed to Covid-19 deaths, they argued, so race itself should be a factor in vaccine distribution.

Elizabeth Ofili, president of the Association of Black Cardiologists (ABC), said the organization supports prioritizing ethnic minorities who have been hit hardest by Covid-19. “The ABC and others have documented that African Americans have poorer outcomes of care regardless of socioeconomic status, and so the vulnerability indices may not capture this type of inequity,” she said.

Alaskan Native people, who experience high rates of poverty and comorbidities, have been at similarly elevated risk of dying from Covid-19. And Ellen Provost, director of the Alaska Native Epidemiology Center at Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, made a related point for these indigenous communities. “If we’re to avoid compounding inequities and increasing disparities…this committee will acknowledge Alaskan Native people are at significant risk of hospitalization and death from SARS-CoV-2, and explicitly place this population in the highest priority group for Covid-19 vaccine risk allocation and distribution,” said Provost.

Other speakers in the public meeting emphasized that prioritizing distribution isn’t enough. Once a vaccine is available, the distribution system must work with healthcare leaders in minority groups in order to ensure adequate access.

There’s considerable suspicion of vaccines within the Black community and too few Black participants in coronavirus vaccine trials, said Randall Morgan, director of the Cobb/NMA Health Institute, which works to address racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare. Healthcare officials can only distribute a vaccine fairly if they work to address these fears.

Systemic racism isn’t the only problem that vaccine distribution must confront. NASEM’s draft distribution system must figure out how to prioritize other vulnerable groups, such as homeless people and prisoners. The committee is receiving written comments this week, and plans to publish a final report later in September.

The committee was charged with their task by Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health, and CDC director Robert Redfield, and so any recommendations will likely receive significant support from the US government. The CDC has instructed states and some jurisdictions to prepare to distribute a vaccine to high-risk populations as early as late October; the action items distributed by the agency instruct states to “identify and estimate sizes of critical populations,” including “people from tribal communities, and people from racial and ethnic minority populations.”

But the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) is also working on its own guidelines, and until a particular vaccine is approved for public use, it’s difficult to determine exactly how it should be distributed. “The uncertainties we had are overwhelming,” said Foege.

This story has been updated with information about the CDC’s instructions to begin preparing for vaccine distribution.