On Sept. 8, Uber launched one of the more ambitious climate commitments in transportation. By 2030, every car in the service’s 10 largest metro markets in the US, Canada, and Europe will be electric. By 2040, it wants to achieve this goal for the rest of the world.

It won’t be easy going green. Of the 5 million drivers the ride-hailing company employs (or “contracts,” using its preferred term), very few drive electric vehicles (EVs) today. Only 12% of Uber’s trip miles are by hybrid vehicles, and just 0.12% are all-electric in North America. Electrifying the fleet will require more accessible overnight charging, more affordable EVs, and batteries that last an entire day without recharging.

Yet increasing EV adoption will only be the beginning of Uber’s challenges. If it ultimately “aligns [its] sustainability goals” with the Paris Climate agreement targets, as it says it will, much of the company’s success will be out of its control.

Uber acknowledges cutting emissions in its distributed global fleet requires ”address[ing] emissions segments that are difficult to decarbonize and hard for us to influence.” That means the grid itself.

Emissions from electricity generation remain the largest single contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions: 36% of energy-related emissions in 2019. It’s declining, slowly. But to stabilize the climate system, it will need to enter a steep dive.

Uber is on the horns of the dilemma facing every company adopting a net-zero goal, from oil companies struggling to account for their customers’ emissions to multinational corporations operating supply chains representing a fifth of global emissions. It’s hard but possible to tackle a company’s own direct emissions. But how do you account for the infrastructure of the global economy itself?

Theoretically, electric mobility can cut GHG emissions by at least 80%, reports the University of California Davis Institute of Transportation Studies. But governments and century-old utilities like California’s PG&E (founded in 1905), New York’s Consolidated Edison (1823), and Duke Energy (1904), are needed to complete the transformation. Uber recognized that in its 2020 climate performance report: “We call upon cities, governments, and environmental experts to join us in examining critical decarbonization and electrification needs across the transportation sector.” (Uber did not respond to several press inquiries.)

Progress has been slow and steady on that front: The average carbon intensity of electricity is expected to fall 50% relative to 2015 by mid-century in a business-as-usual scenario, according to the University of California, Davis. To fully decarbonize, however, it will cost $4.5 trillion in new investments in the US alone—and likely more than 10 times that globally. In places like China and India, where coal generates 50% of the nation’s electricity, this remains a world away.

For now, Uber and others will be able to make some progress on their own. Rival Lyft announced an all-electric push for 2030 (without vehicle subsidies). Globally, aviation and shipping moguls are elevating their rhetoric about phasing out fossil fuels (with modest progress). Major automakers are committing to all-electric lineups as they chase Tesla’s wild success.

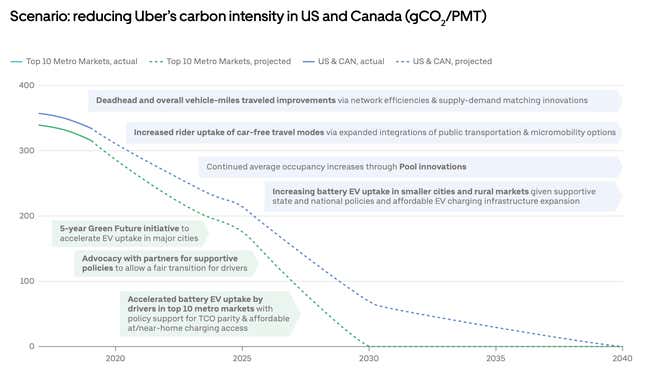

Uber reports that its carbon intensity (emissions per mile) fell 6% between 2017 and 2019 even as average active monthly ridership rose. In its plan released this week, the company said it will devote $800 million to EV discounts with partner automakers (General Motors and the Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi alliance) through 2025. Passengers now have the option to request more fuel-efficient rides, and pay a slight surcharge for EVs.

And despite fossil fuel-heavy grids, battery-powered vehicles will still emit less carbon dioxide than a petroleum-powered car in the vast majority of cases, multiple analyses have confirmed. A 2019 analysis by Carbon Brief found a Nissan Leaf in the UK emits nearly three times less GHG over its lifetime than a conventional car, comparable to the EU average, and that number will be even lower 10 years from now as grids push out fossil fuels and EV manufacturing demands less energy.

Beyond this, it will be cities, nations, and utilities that decide just how green Uber can be in the coming years. If the Ubers of the world want to zero out emissions and keep warming under the 2°C target set by the Paris climate accords, it will take far more than any one company can muster.