The difference between shareholder and stakeholder capitalism

The debate over shareholder versus stakeholder capitalism has been going on for decades, and it has been especially fraught in recent years.

The debate over shareholder versus stakeholder capitalism has been going on for decades, and it has been especially fraught in recent years.

Proponents of shareholder capitalism say corporations have one purpose—to make as much money as possible for their shareholders—and that attempting to do anything else would backfire. People who back stakeholder capitalism say companies should consider all their stakeholders—not just the owners, but also employees, customers, and suppliers—and that doing otherwise means companies may well damage the environment while entrenching inequality.

Both sides can point to some eye-popping statistics in America, the country which is perhaps ground-zero for shareholder primacy. The US poverty rate declined to 10.5% last year, the lowest since records were first published in 1959. At the same time, inequality has risen, with the top 20% of highest earners taking home more than half of US income. Gender and racial disparities have have eased only slowly or, in come cases, not at all: the income gap between white and Black households has barely changed since the 1970s.

Most people think there need to be changes if countries like the US are to stop large chunks of society from falling behind the more privileged, and if society is to protect the planet from environmental dangers like climate change. But that’s where the agreements end. Quartz reviewed the pros and cons, and where we might go from here.

Who supports shareholder primacy?

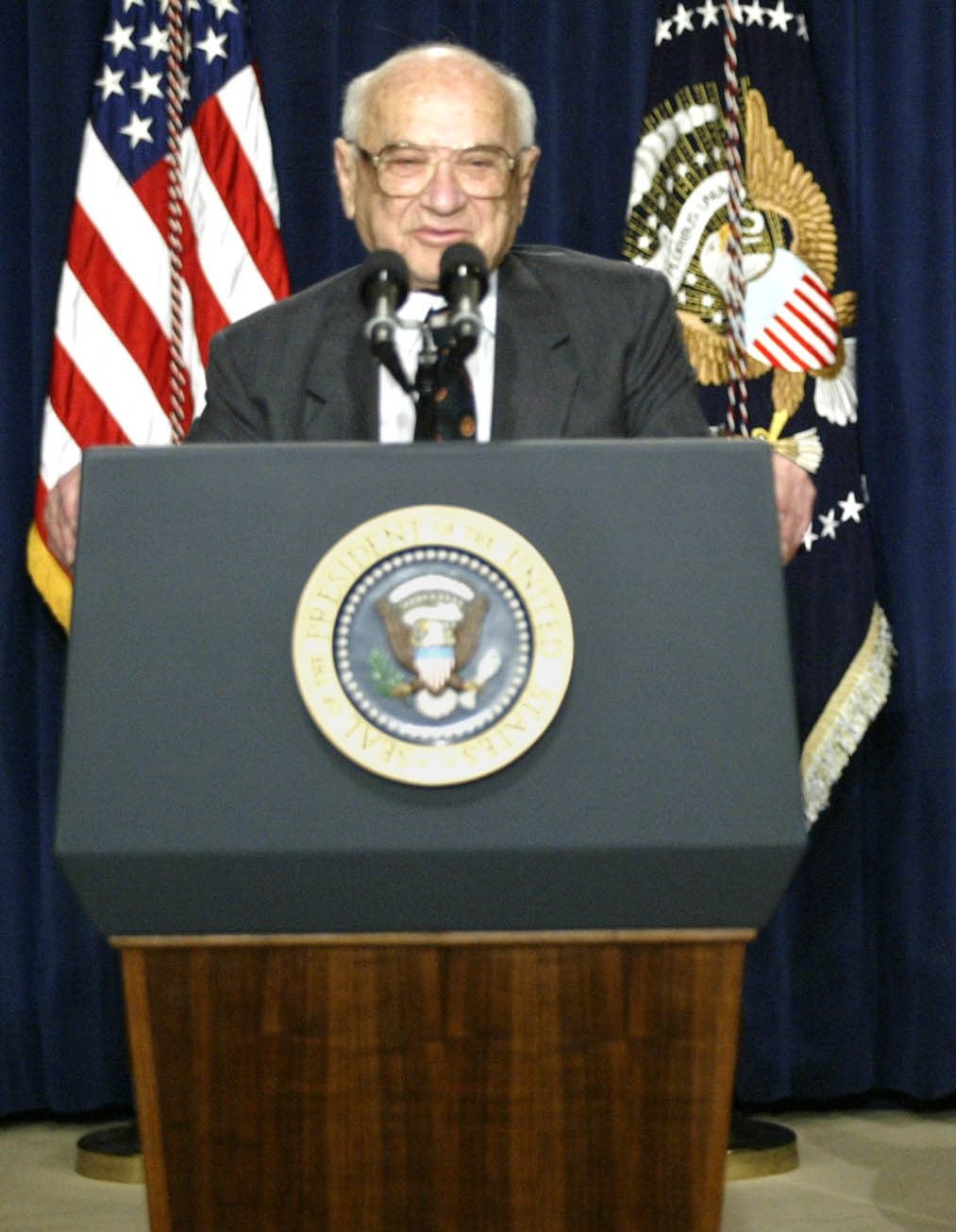

University of Chicago economics professor Milton Friedman is considered the godfather of shareholder primacy—the view that a corporate executives’ only social responsibility is to increase profits for the owners. (Though his predecessors were debating this topic back to the 1930s.) In his seminal New York Times essay in 1970, the future Nobel Prize winner argued that holding these executives responsible for stockholder returns is clearly defined and can be measured. Expecting executives to simultaneously account for other social responsibilities would mean “spending someone else’s money for a general social interest.”

For Friedman, an executive looking out for multiple stakeholders is like an unelected official who is taxing shareholders and spending money as they see fit, with little in the way of accountability. The executive would struggle to resolve competing stakeholder interests (customers want lower prices, but lower prices make it harder for employees to have what they want, which is higher pay). Even worse, the executive could use “social responsibility” as a gambit to avoid taking any responsibility at all. Friedman’s argument resembles Adam Smith’s assertion in The Wealth of Nations that pursuing one’s own self-interest often ends up helping society more than when one is trying to.

Some think it’s the role of the government, rather than businesses, to assess what’s good for society. Elected officials can then create regulations to meet those aims. Indeed, Friedman’s essay contains a caveat that doesn’t get talked about as often: The corporate executive should make as much money as possible for shareholders “while conforming to the basic rules of the society, both those embodied in law and those embodied in ethical custom.” Some probably see this sentence as a slender reed that’s crushed under the weight of greed, while others may think it can constrain the excesses of market forces while allowing them to generate prosperity.

Who supports stakeholder capitalism?

Advocates of stakeholder capitalism include the Business Roundtable, an association of executives running some of the biggest American companies, and Klaus Schwab, founder of the World Economic Forum, who say corporate executives should consider a broader set of interests than just shareholders. In 2018, Larry Fink, the founder and CEO of BlackRock, acknowledged that the economy since the 2008 financial crisis had benefitted the wealthy, while prosperity and stability had slipped away for many regular people. “Companies must benefit all of their stakeholders, including shareholders, employees, customers, and the communities in which they operate,” wrote the chief executive of the world’s largest asset manager. In 2020, BlackRock advocated for an investor focus on sustainability.

Columbia university professor Joseph Stiglitz, another winner of the Nobel Prize for economics, says his research with Sandy Grossman disproved Friedman’s ideas during the same decade Friedman published his essay, and that shareholder wealth maximization doesn’t maximize societal welfare:

This is obviously true when there are important externalities such as climate change, or when corporations poison the air we breathe or the water we drink. And it is obviously true when they push unhealthy products like sugary drinks that contribute to childhood obesity, or painkillers that unleash an opioid crisis, or when they exploit the unwary and vulnerable, like Trump University and so many other American for-profit higher education institutions. And it is true when they profit by exercising market power, as many banks and technology companies do.

In early 2020, Stiglitz suggested policymakers should focus on things like reducing executive and management pay to counteract pay disparities, making sure companies are paying their fair share of taxes, and increasing workers’ bargaining power through stronger unions. He has called for a model that rebalances government, markets, and society, in what he describes as progressive capitalism.

Who are the stakeholders?

The Business Roundtable, which includes the likes of JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon and Ford Foundation president Darren Walker, said in August 2019 that it advocates a commitment to all stakeholders:

- Delivering value to customers.

- Investing in employees by compensating them fairly, providing training and education, fostering diversity and inclusion, and providing dignity and respect.

- Dealing fairly and ethically with suppliers.

- Supporting communities by respecting the people in them, and by protecting the environment through things like sustainable practices.

- Generating long-term value for shareholders, and providing transparency and effective engagement with them.

How to fix it

Long-term: Some say shareholder primacy is almost by definition a short-term perspective, a policy that allows business leaders to make decisions that produce a quick buck but has damaging long-term consequences. Those consequences might include harm to customers (selling addictive or sugary products), treating employees poorly (underpaying them, or forcing them to work in unsafe conditions), or damaging the communities where they’re based (dumping industrial chemicals into the soil or water).

Erika Karp, the chief executive of Cornerstone Capital Group, wrote that Friedman’s essay could be improved by adding the words “long term,” which enshrine a more thoughtful use of corporate resources. (A careful reading of Friedman’s writing suggests that the economist was disparaging of short-term horizons.) Yet Michael Faulkender, a finance professor at the University of Maryland, says the stock market and shareholder primacy already reward long-term thinking, because equity prices reflect future (not current) earnings.

Campaign finance reform: On the 50th anniversary of Friedman’s essay, the New York Times published the views of 22 experts who commented on the legacy of shareholder primacy, and the word “campaign” came up five times. While Friedman wrote that corporate executives should conform to society’s rules and laws, there’s a strong argument that this brake has been disengaged by millions of dollars of lobbying. “The government should be passing laws to discipline profit-maximization behavior, but too many lawmakers have themselves become the employees of the shareholders—their electoral success tied to campaign contributions and other forms of deep-pocketed support,” wrote Marianne Bertrand, professor of economics at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business.

B corporations: These businesses pledge to assess themselves in terms of governance, workers, community, environment, and customers. For a company to become a certified B Corp, it must score a minimum of 80 points out of a possible 200 across those five areas. Auditors from B Lab verify the company’s claims, and accredit it if the 80-point threshold is met. Companies pay an annual certification fee based on their size and have to re-certify every three years.

Davos Manifesto: The declaration states that companies should pay their fair share of taxes, have zero tolerance for corruption, uphold human rights through their supply chains, and promote a competitive and level playing field.

Does stakeholder capitalism work?

It’s an open question. Stiglitz suggests that some of signers of the US Business Roundtable’s statement were disingenuous, as they continued to avoid paying their fair share of taxes; some of those executives supported US tax law changes in 2017 that cut levies on corporations and the wealthy.

Ben & Jerry’s, the ice cream maker that is one of the best known B Corporations, was sued by an environmental activist because much of the milk it uses doesn’t come from “happy cows,” as indicated on its product packaging, but rather from cows on regular industrial farms. (The lawsuit was dismissed, and Ben & Jerry’s removed the “happy cows” labelling from its packaging.)

A company won’t survive in the absence of profits. But in some respects, the two sides may be, at least at times, more aligned than they seem. When it comes to executive pay, research indicates that companies with the highest paid executives tend to perform worse for shareholders. This implies that some stakeholder ideals would be beneficial for shareholders (indeed, high CEO pay suggests some corporations have been run in the interests of executive management and not of investors).

Changing how companies are run isn’t an all-or-nothing proposition. Rebalancing the economy may require something of everything—pressure from society when executives don’t conform to its ideals, a more muscular and less conflicted government that can again act as a check against powerful corporations, and a generation of executives with a long-term vision.