Over a few days in late February and early March, the biggest five banks in the US collectively published more than 1,600 pages worth of financial reports. Simply reading—much less understanding—these monsters is a Herculean task.

Heavily regulated and intensely litigated, banks are a special case, but even the average US-listed firm filed a hefty 152-page annual report with the Securities and Exchange Commission in its latest financial year, according to the Wall Street Journal (paywall). This isn’t exactly a breezy read for harried analysts, either.

Two Notre Dame professors think that long reports should be a red flag for investors. In a forthcoming paper in the Journal of Finance, Tim Loughran and Bill McDonald crunched the numbers on every annual report filed with the SEC since 1994—more than 66,000 filings—to see what effect report length had on investors’ understanding of a company’s prospects.

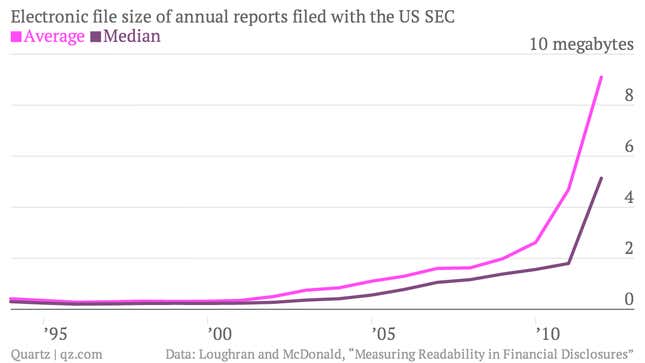

The existing literature on the readability of reports focuses on textual analysis, using the length of sentences and complexity of words to gauge the difficulty of understanding a report. But Loughran and McDonald reckon that the sheer length of a report matters more than what’s inside. To test their theory, they compared the file size of plain-text reports published electronically with the SEC to various measures of market volatility, from stock price movements to the dispersion of analysts’ earnings forecasts.

The researchers found that the size of a report was a better predictor of subsequent market volatility than traditional measures of readability. “The less material investors and analysts must digest to get valuation-relevant information from company managers, the better they are at predicting subsequent value-relevant events,” they conclude. It’s a worrying sign, then, that financial reports have been ballooning in size recently:

The thicket of rules that US-listed firms must navigate is often blamed for page inflation, and the professors think that regulators can do something about it. The SEC “should emphasize to filers that the benefit of exhaustive disclosure in the interest of litigation avoidance must be balanced with the costs of information overload,” they write.

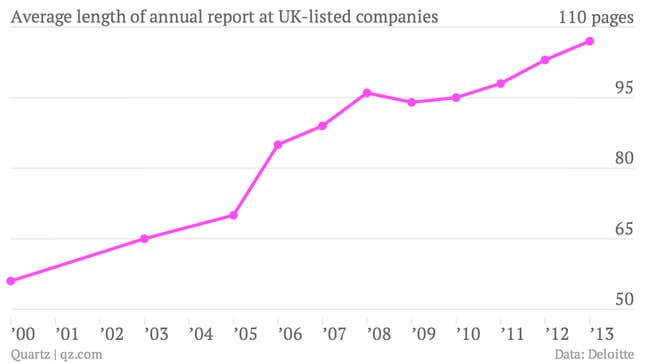

Convincing risk-averse regulators and corporate lawyers to keep it short is probably a fool’s errand. And this is not only a problem in the US. Here is the trend for annual reports issued by UK-listed companies:

If the latest research is true, the size of an annual report could serve as a simple gauge of a stock’s future volatility. This is hardly how financial reports are intended to be used, but even the keenest analysts are unlikely to wade through novel-length disclosures (warning: 494-page pdf) every quarter for every company they cover. What is comprehensive is not necessarily comprehensible.