Brits are unwittingly pouring their savings into oil and tobacco companies

Last year, hundreds of thousands of people—from students to retirees—joined immense demonstrations in the UK, calling for the country to cut its carbon emissions to battle the threat of climate change. Their sheer numbers showed a swelling commitment to the cause.

Last year, hundreds of thousands of people—from students to retirees—joined immense demonstrations in the UK, calling for the country to cut its carbon emissions to battle the threat of climate change. Their sheer numbers showed a swelling commitment to the cause.

Yet, if financial research is any indication, many of them are missing a critical opportunity to shape the future they want. Most employed people in Britain are automatically placed in a pension plan, and they can usually control where that money goes. Research shows that the vast majority of that investment goes into a default fund, which is likely piping capital into mining and energy companies that people concerned about climate change would probably rather avoid.

“People might be making all these choices in the daily lives and might be recycling and having shorter showers and flying less, but, actually, if they were to make the right choices in their pension plan they can make a much bigger impact on all these areas that they care about,” said Maria Nazarova-Doyle, head of pension investments at Scottish Widows.

Or put another way: The boring, banal retirement portfolio could be as important as mass protests when it comes to climate change.

Investing inertia

UK employees are automatically enrolled in a workplace pension, which, these days, is typically a defined contribution plan. That means you decide how the money should be invested. How much you have available at retirement will depend on how much you save and how well those investments perform over the years. In the US, 401(k) plans are also defined contribution.

The vast majority of Brits—around 90% or more—let the money flow into whatever default fund their employer has chosen for them, according to research by pension provider Scottish Widows. Some people likely trust their employer to have done the work for them and to have picked a decent all-weather portfolio. Others may think they don’t know enough about investing to alter their plan.

But that’s a mistake for anyone who cares about things like carbon emissions, diversity, workplace safety, or making money on controversial things like nicotine addiction. Research indicates that this default-fund inertia is also alive and well in US 401(k) plans.

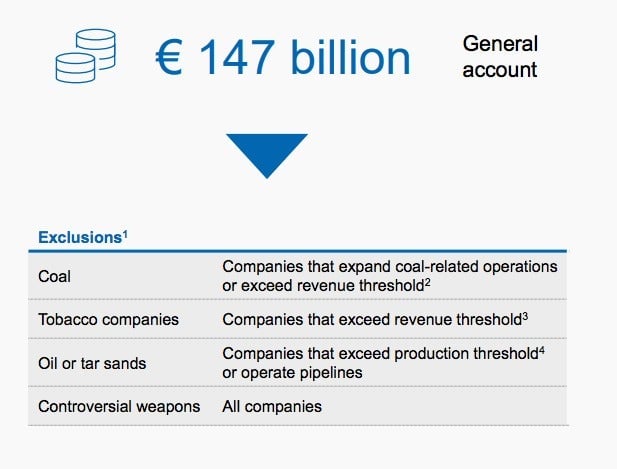

A default fund offered by Aegon, the asset manager with its headquarters in The Hague, is illustrative. The company says it runs the market leading investment platform in Britain, with 3.9 million customers in the UK. A presentation dated September 2020 says Aegon excludes investments in things like coal, tobacco, and oil and tar sands, depending on certain revenue thresholds (disclosure: Quartz is an Aegon customer):

However, the firm’s £1.2 billion ($1.6 billion) Aegon Workplace Default fund invests in oil and tobacco companies. Its documentation shows that the money goes into five index-tracker funds. These funds, which follow a benchmark that tracks a large collection of securities, typically charge lower fees than ones that have an active portfolio manager. That’s often seen as a good thing, as research indicates that few money managers are skilled enough to outperform the overall market. Passive tracker funds are cheaper and perform better than many active funds.

But if you care about things like environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues, which seek to take into account factors like climate impact, or just generally would like to avoid putting your money into mining, energy, and tobacco companies, you might be disappointed by some of its holdings. Aegon has certain exclusions for its proprietary funds, but those exclusions don’t apply to funds from other providers. Some 32% of the Aegon Workplace Default fund goes into Aegon’s UK Index Tracker, which counts British American Tobacco, energy companies BP and Royal Dutch Shell, and mining company Rio Tinto among its top holdings:

Another fund that employers can offer as default, the Aegon 50/50 Global Equity Index Lifestyle fund, counts those stocks among its top 10 holdings. Richard Whitehall, head of portfolio management at Aegon, said the company is going to announce plans later this year to embed ESG principles throughout its workplace default funds. Most default ESG strategies are only available for stocks, but he said the company is in discussions with fund providers to offer ESG criteria in other types of assets, like bonds, at a competitive price.

“We support the need to integrate ESG within workplace default funds and as part of our commitment to improving and expanding our range of sustainable and ethical solutions,” he wrote in an email. “Over time we expect the ESG proportion to steadily rise. Aegon UK’s main default fund, LifePath, already integrates ESG factors into its investment mix in the growth phase with allocation to global ESG equities. We also offer an ethical fund which firms can choose as the default for their employees.”

Nazarova-Doyle says Scottish Widows is transitioning its $35 billion default fund toward assets that are more in line with ESG principles. The company’s default Pension Investment Approach (PIA) also has holdings in a UK tracker fund that invest in a broad swath of companies, including British American Tobacco, energy companies BP and Royal Dutch Shell, and mining company Rio Tinto.

“If you’re trying to make changes to a $35 billion portfolio, it’s a big project and it takes time,” Nazarova-Doyle said. “We’re trying to integrate ESG into what we do, on behalf of 2.6 million people that we have in the default.”

Are dirty companies more profitable?

Some investors may be wary of an ESG-focused portfolio because they think it won’t make as much money. Consulting firm EY says there’s a growing body of evidence signaling there’s not a tradeoff between financial returns and what is considered responsible investing. In research published this month, EY and life insurer Royal London said they reviewed 30 published papers and found that ESG principles can boost corporate performance and investment portfolio returns.

“It is a bit of bugbear of ours that people think you have got to make a choice between better returns and being ESG aligned,” said Gareth Mee, partner in sustainable finance consulting at EY. “There is loads and loads of evidence now that you don’t have to make a choice.”

That said, some strategies that exclude a wide range of companies have underperformed versus the broader markets. While ESG may consider a fairly broad set of factors like the quality of a firm’s governance, the diversity of its board, and climate-change resilience, a fund focused on ethical investing could narrow its investment options even more. Such a strategy might exclude, say, all companies that have anything to do with animal testing. Even so, some surveys indicate that 40% of more of investors would accept lower returns if the portfolio better matched their principles.

“Ethical is very exclusionary,” Nazarova-Doyle said. “You might end up with a narrow universe that is more volatile, and over time it tended to not perform that well.”

Even an ESG label doesn’t guarantee that aspiring retirees will consider those stocks to be responsible investments. For example, one data provider might give a company a higher ESG score because of its future commitments, while another data provider might score the same company based on what it’s doing right now, EY’s Mee said. ESG criteria isn’t standardized, meaning companies can end up reporting these metrics differently, or not at all.

For example, Sustainalytics, part of financial research company Morningstar, gives British energy company BP a “high risk” ESG rating of 37.4, while French energy company Total gets a “medium risk” ESG rating of 27. By contrast, social media company Facebook is assigned a “high risk” score of 31.4. MSCI, another financial data provider, gives Facebook a BBB, or “average,” ESG rating in its industry.

Tech giants

Some ESG funds have performed well recently because they can be heavily loaded with tech giants like Google and Facebook. While those stocks have rallied this year, not everyone is comfortable with the business models used by search and social media giants, which rely on controversial surveillance of their users to sell ads.

Hester Peirce, a commissioner at the US Securities and Exchange Commission, criticized ESG in a speech last year, saying the ratings are “broad enough to mean just about anything to anyone.” The scores are so ambiguous, she said, that ESG experts can impose their own judgments, “which may be rooted in nothing at all other than their own preferences.”

EY’s Mee thinks ESG data are getting better every day, and that “ESG aware” funds may increasingly become the default setting for pension investing. But even that wouldn’t be a panacea for the $100 trillion industry. Some providers may nudge new pension enrollees toward ESG investments, while leaving the bulk of the historical holdings in traditional funds.

That means default funds, and just relying on ESG ratings, may not cut it for some people. For the foreseeable, retirement savers are going to have to do their homework if they want to make sure their pension money isn’t actively working against their own beliefs. Admittedly, that’s not always a simple task, as it can be tricky to figure out what a fund is holding. When retirement funds invest in a series of index funds, it can take some digging to uncover what exactly is in those index funds.

Sandy Trust, a senior manager at EY, says investors should look at it as an opportunity. If the whole point of a pension is to have a better future, then it makes sense that that pension should be using its capital to make the world better now. “Clearly that future is not going to be better if we have catastrophic climate change, great inequality, and the only animals alive are chickens and cows,” he said.