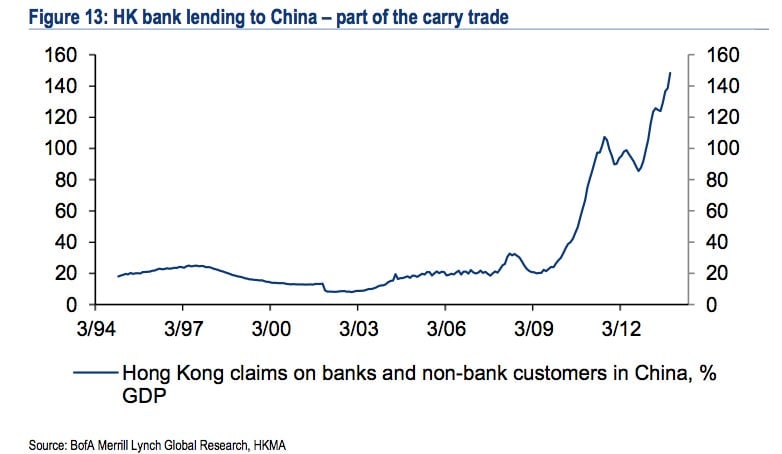

Hong Kong banks have loaned 165% of the territory’s GDP to China

A few years ago, Hong Kong banks had issued almost no loans to mainland China. Now that number is at nearly $450 billion, according to the Hong Kong Monetary Authority.

A few years ago, Hong Kong banks had issued almost no loans to mainland China. Now that number is at nearly $450 billion, according to the Hong Kong Monetary Authority.

The regulator reports that, at the end of 2013, nearly 40% of Hong Kong banks’ total loan books were net claims on China, up from zero in 2010. Here’s a look at that trend as of Q3 2013 (some more recent charts from Reuters are here):

This mainland vulnerability of Hong Kong banks is stoking anxiety among investors. Not only is the country’s economy rapidly slowing, but a recent spate of defaults highlights the dire financial straits of many of the country’s borrowers, particularly those borrowing through shadow channels, which evade the balance sheets—and, therefore, required capital buffers—of Chinese banks. Bank of East Asia is the worst off, with 46% of its loans to China, says Reuters.

There are a good reasons this may sound way worse than it is. Hong Kong banks are required to hold relatively large amounts of capital as a buffer against default. In addition, a good portion of those “loans” are actually trade finance, credit issued to facilitate Chinese imports and exports that’s usually considered low risk because it’s short-term.

A lot of the credit recorded as “trade finance” isn’t, though.

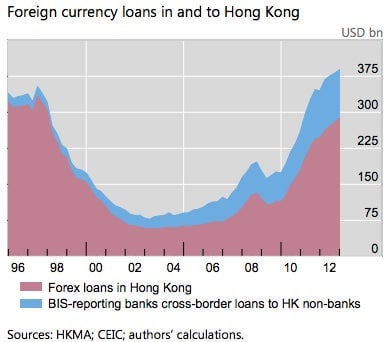

As we’ve discussed in the past, over-invoicing of exports has been a popular way of profiting on the mainland’s relatively high borrowing costs and the appreciation of the yuan against the dollar. Reporting the fake sale of exports allows traders to bring more yuan into the mainland than they actually earned settling their export order. That extra cash comes from borrowing dollars from Hong Kong banks at low rates, which traders swap for yuan. Instead of holding those in low-yielding Chinese bank accounts, many traders invest in shadow finance products, particularly in trust loan products, according to Bank of America/Merrill Lynch in a February note.

This and other methods of betting on yuan appreciation contributed to around $500 billion of yuan bets outstanding as of February, when the government began weakening the yuan. The yuan recovered somewhat against the dollar today. But any trader who didn’t cover their yuan bets with hedges lost money a lot of money as a result of the yuan’s nearly 3% drop since late February. An anonymous source told Reuters loan defaults from these losses could hit Hong Kong banks.

Some of that hot money came from banks in Taiwan, Singapore, the UK, and possibly South Korea. That’s part of why Standard and Poors, a ratings agency, says a Chinese “hard landing”—a drop to 5% annual GDP growth—would hurt many Asian banking sectors. But Hong Kong banks, says S&P, would “suffer significant credit losses” on their loans to the mainland.