Despite China’s exchange-rate reform, its hot money woes are still scary

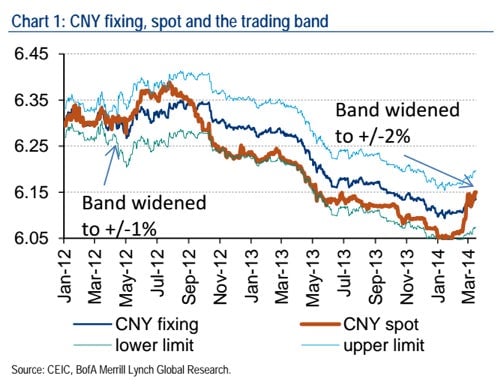

Starting today, the Chinese government allowed the yuan to trade in a 2% band around the daily “fixing” or “reference” rate (meaning, the value the People’s Bank of China sets against the dollar before trading each day.) This move appears to be in line with the Chinese government’s stated objective of letting the market, and not policy, set the yuan’s value—a sign that the country is “pushing ahead with a campaigns of wide-ranging financial overhauls,” as the New York Times put it (paywall).

Starting today, the Chinese government allowed the yuan to trade in a 2% band around the daily “fixing” or “reference” rate (meaning, the value the People’s Bank of China sets against the dollar before trading each day.) This move appears to be in line with the Chinese government’s stated objective of letting the market, and not policy, set the yuan’s value—a sign that the country is “pushing ahead with a campaigns of wide-ranging financial overhauls,” as the New York Times put it (paywall).

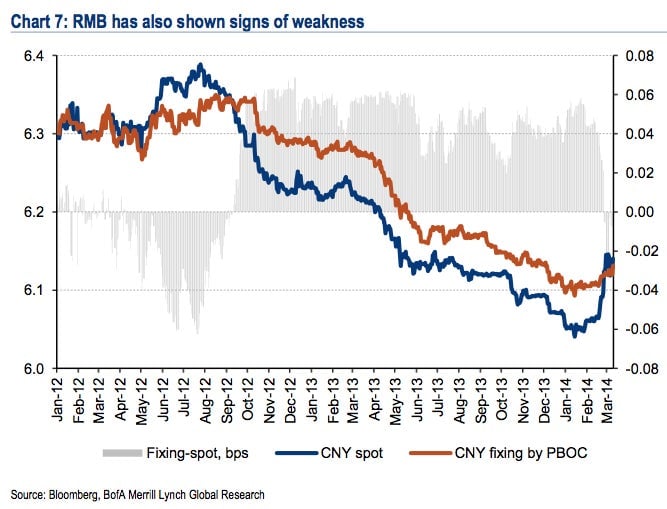

But economists also think that, along with the sharp weakening of the yuan since February 17, the PBoC hopes band widening will deter hot money, speculative capital that investors move into and out of a country very quickly.

Hot money tends to flow into a country whose interest rates are higher than those of other major countries or whose currency is thought to be undervalued, often boosting property prices or stock markets. A change in conditions can cause hot money to abruptly reverse course. For example, hot money that had been flowing into Southeast Asia throughout the 1990s began fleeing those countries as the Asian financial crisis set in in 1997, exacerbating economic slowdown.

Though economists differ on which way hot money might flow as a result of the latest exchange-rate reform in China, many say the latest move doesn’t do much to diminish the risk of destabilizing hot money flows.

China’s central bank has a love-hate affair with hot money inflows. As of February, at least $500 billion in hot money had gushed into China, much of it into dodgy shadow finance and property investments. While these inflows make it hard for the PBoC to manage liquidity, inflation, and systemic risk, they also provide steady cash infusions, preventing cash crunches like those that happened in June and December of 2013 from happening more frequently. Outflows of hot money, on the other hand, threaten the Chinese economy, both by draining liquidity and upping the risk of a snowballing confidence crisis that would hurt stock and property market values.

The wider band won’t discourage hot money inflows, argues Wei Yao, economist at Société Générale, because the “the market will continue to take the reference rate as the PBoC’s policy intention for the direction of the yuan, even when the PBoC does not intend so.” In the past, this has led to a self-reinforcing conviction that the government wants the yuan to strengthen, wrote Yao in a note today, encouraging hot money inflows. As long as the PBoC sets the reference rate, it risks inviting more policy-based speculation, says Yao.

However, Ting Lu, economist at Bank of America/Merrill Lynch, argues that increased volatility created by the widened band will prevent that. And capital outflow isn’t a major risk, he writes in a note today, because China’s $3.8 trillion in foreign exchange reserves provide plenty of ammunition to defend the yuan’s value should capital flight cause the currency to shed value. In addition, BofA/Merrill Lynch’s Lu says, the PBoC has sufficient policy tools to inject liquidity, such as by lowering the reserve requirement ratio, or by buying government debt. Plus, he says, most people believe the yuan is currently close to equilibrium against the dollar, which should discourage speculative bets.

David Cui, equity strategist at BofA/ML, agrees that China’s forex stash should prevent a big yuan weakening. However, February’s out-of-the-blue trade deficit and the abrupt weakness in copper and iron ore prices may indicate that hot money is already fleeing China, Cui argued last week. Rampant overcapacity—and the likelihood that the government will keep the currency cheap relative to the dollar to support exports from those sectors—may continue to push hot money out of China.