In China, it’s beginning to look a lot like June—at least in terms of the country’s cash flow. The liquidity shortage that started last week worsened again today, harking back to its worrisome cash crunch last summer. The troubles have persisted despite last week’s 300 billion yuan ($49.4 billion) injection of emergency funds by the People’s Bank of China, the central bank.

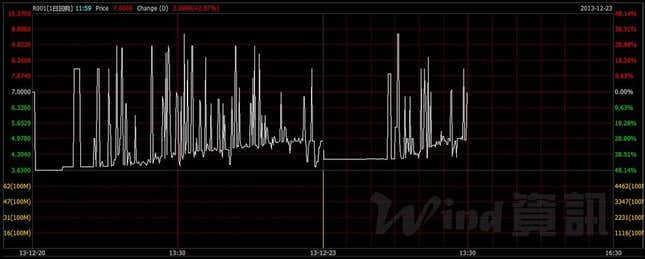

While the overnight bond repurchase rate, which reflects short-term liquidity, climbed to 9.5% today, the seven-day rate hit 10%, reports Reuters, higher than Friday’s average—and the highest it’s gone since late June, when a liquidity crisis flared up. In other words, Chinese banks charged each other three times the interest for an overnight loan as a US bank requires for a 15-year loan, as Anne Stevenson-Yang of J Capital Research pointed out.

Some of this is seasonal. At the end of each quarter, banks must round up deposits in order to meet regulatory requirements. And though a big chunk of loans start maturing about now, banks will need to roll these over, as Reuters reports.

The government is clearly worried. Chinese censors have banned the term “cash crunch” (paywall), reports the Financial Times. In addition, trading today opened suspiciously low, prompting some traders to suspect that the central bank was intervening to drive down rates, reports Reuters.

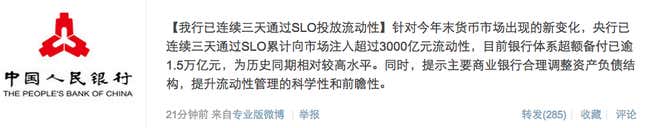

And after markets closed on Friday, the PBOC took to Sina Weibo to announce that it had injected 300 billion yuan into the financial system over three days, breaking with its policy of announcing such injections a month after they happen. The PBOC’s message also emphasized that banks have 1.5 trillion yuan ($247 billion) worth of excess reserves, which it says reflects sufficient liquidity.

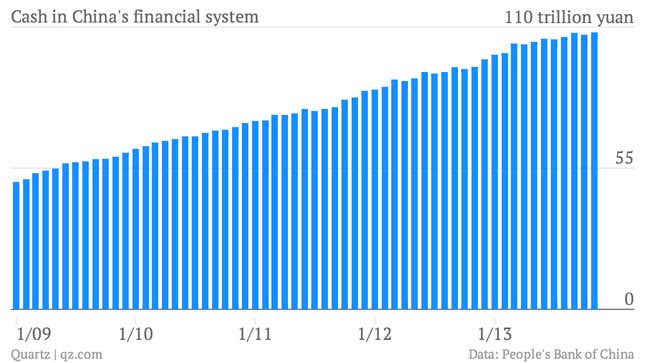

The argument that there’s enough cash in the system is being pushed by China’s financial media. Take, for instance, the state-backed Shanghai Security News’ reports today, which said the cash crunch is “absolutely not a shortage of money“ (link in Chinese), but rather that it “results from the distorted funding structure of banks,” as the FT flagged (interestingly enough, the authors of the SSN piece were allowed to use the term “cash crunch”). Pointing to the fact that, as of the end of November, the system had 107.9 trillion yuan in cash, the article argues that only structural reform will “solve the fundamental conditions of the ‘cash crunch.'”

That’s a lot of money sloshing around. The recent interbank seize-up may suggest that banks are hoarding cash. But as many banks are evergreening loans even though they are increasingly desperate for deposits, it could also mean they simply don’t have enough money. So where might this cash be instead? Tied up in risky shadow lending-funded projects, perhaps. Though reforms are needed to fix this, the economy still needs cash to run. Today’s surge of interbank rates reflects what a tough spot the PBOC is in. It will need to keep pumping money into the system in the next year in order to keep the economy moving. But the looser the money, the harder it will be to push for reform.