America’s largest banks are steeled for a wave of loan defaults and missed payments that still haven’t arrived. Thanks to an initially immense amount of support from Washington, that pain appears to have been pushed out to next year.

Bank of America, the country’s second-biggest lender by assets, gives us a window into how households are holding up. Its customers have spent $2.3 trillion this year, which is more than they dished out during that span in 2019, Bank of America CEO Brian Moynihan said in a call with analysts this week. Credit card and mortgage delinquencies were lower in the third quarter than they were a year earlier—which is not what you would expect to see in a country in which around 800,000 or more people make new filings for unemployment support each week.

Executives at Bank of America, like their peers at JPMorgan and Citigroup, credit government stimulus, like the $2 trillion CARES Act, for preventing a meltdown. It remains to be seen whether government support has merely delayed heavy losses, or created a bridge for consumers and business until they to get to the other side of the economic malaise.

“The purpose of it was to change the outcome, not just delay the losses,” JPMorgan CFO Jennifer Piepszak told analysts this week. “The question is whether the bridge will be long enough and strong enough to bridge people back to employment, and bridge small businesses back to normalcy.”

The US banking giants accounted for heavy losses to come during the first and second quarters, but added much less to those provisions in the most recent period. Bank of America’s CEO said the lender’s build up of reserves is already behind it and factored into its financials.

As Bank of America’s Moynihan pointed out, the expectation for losses keeps getting pushed out, quarter after quarter. “It’s now in the second half of next year,” he said. JPMorgan’s CFO echoed that idea, as did Citigroup’s: “We do expect losses to begin to rise next year and likely peak towards the end of 2021 as government stimulus and other programs roll off and unemployment remains elevated,” Citigroup CFO Mark Mason said.

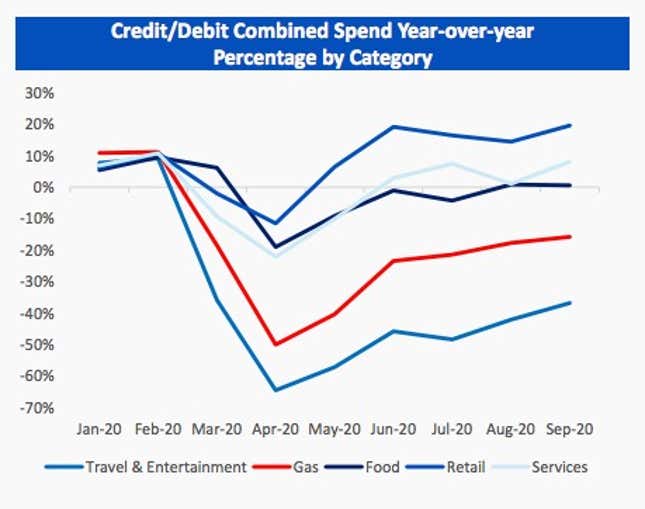

This week’s bank results also highlighted how unevenly the coronavirus pandemic has rippled through the US economy. At Bank of America, customer spending on retail and services has bounced back and increased, as of the third quarter. But other sectors remain deeply distressed, with travel and entertainment spending still 37% lower than a year ago. Expenditures at restaurants have come off their April lows, but they’re still down 18% from 2019.

For now, the big US banks appear heavily buttressed against the potential turmoil. Many lenders have cut dividend payments and stock buybacks, fortifying their balance sheets, and deposits have shot up. “Capital is building up and deposits flows have been very good, for the obvious reasons,” said David Ellison, a portfolio manager at Hennessy Funds. “When the world is coming to an end everybody puts their money in the bank.”

Will Congress pass a new stimulus bill?

Investors of all stripes have been fixated on whether Washington will provide more support. The fiscal injection from the CARES Act is still probably giving the US economy some propulsion, but that support is tailing off, notably for the unemployed, whose additional benefits have expired. House speaker Nancy Pelosi and Treasury secretary Steven Mnuchin have been negotiating a new stimulus deal amounting to somewhere between $1.8 trillion and $2.2 trillion, but an agreement still appears out of reach.

When it comes to planning, JPMorgan said the bank isn’t counting on more government support after this year, and Bank of America CFO Paul Donofrio said it’s too soon for the company to alter its commercial reserves. “Despite the macro improvement, there is still too much uncertainty around unemployment, expiration of stimulus, the duration of the pandemic to reduce total reserves,” he said.

While America’s mega banks can get by without more government support, it’s a different matter for Main Street and for people looking for jobs. “A stimulus plan would help the unemployed,” Moynihan said. It would support “the businesses that are still struggling to get their business capacity—get their business utilization up, those obvious businesses we all know, and then states and towns so they don’t have further reduction in budgets in schools and other things, the hospitals. All of these people have been heavily affected.”

The impact of low interest rates

Once they get through an expected increase in loan losses next year, banks will have another major headwind from low interest rates. A key money maker for lenders is their net interest margin—the gap between the interest they pay out to customers in deposits, and the interest they collect from customers on loans. Rates on bank loans and mortgages typically follow Treasury yields, which are hovering around the lowest on record. As interest rates plunge, that net interest margin, which accounts for half or more of revenue for most banks, tends to get squeezed.

Banks have been here before. The Federal Reserve slashed interest rates after the 2008 financial crisis and embarked on a series of programs to tamp down borrowing costs. But Ellison fears that this time could be different, as the US becomes more like Europe and Japan, which have long been beset by ultra-low or even negative interest rates. He thinks investors in banks stocks have yet to reckon with that risk.

“If you go back to 2009, 2010, 2011, when rates were low, it was OK because everybody viewed that as being temporary,” Ellison said. “People are starting believe we’re going to be like Japan, we are going to be like Europe, and we’re heading in that direction, and these margins are more permanent than they are transitory.”