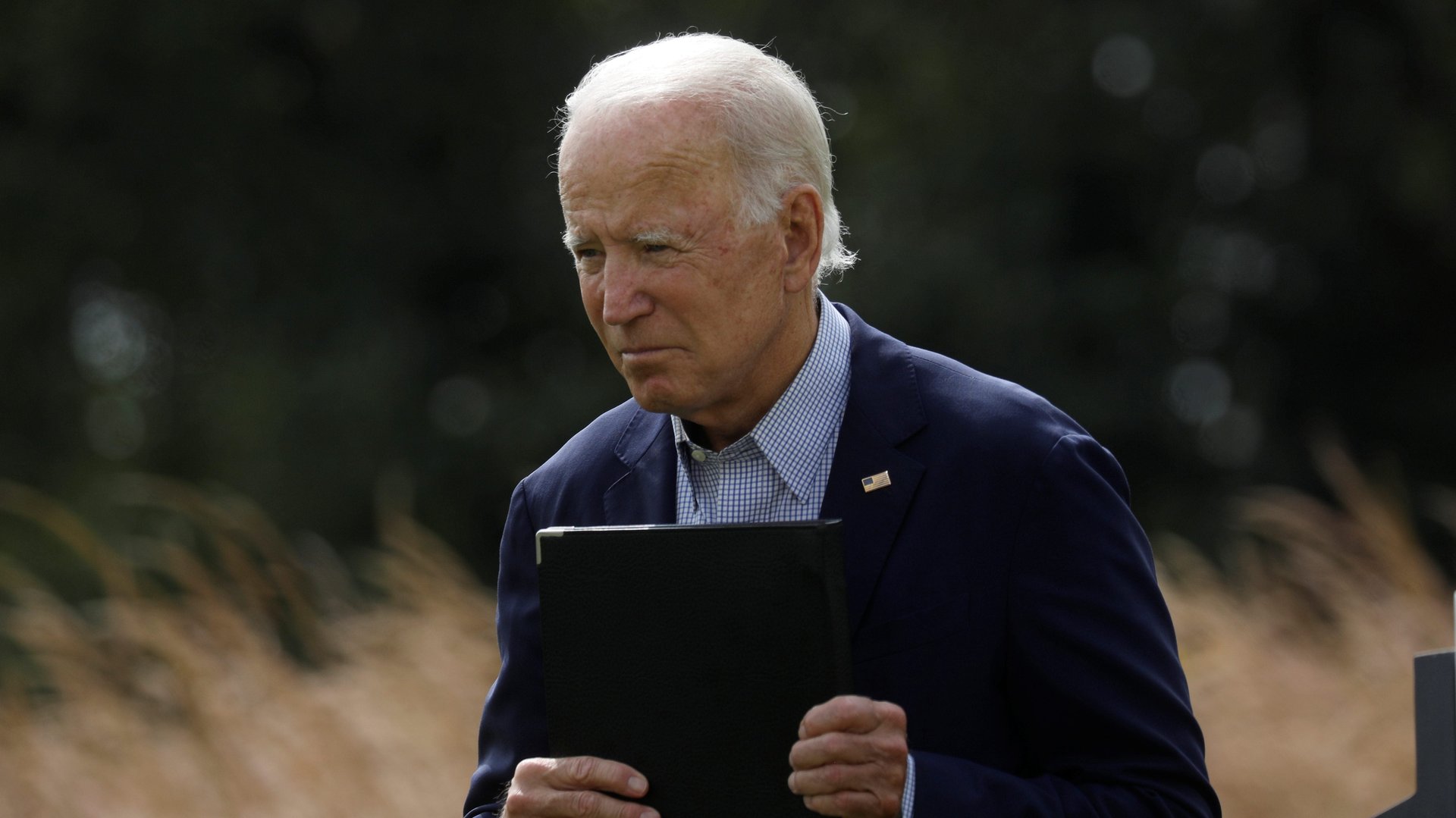

How Biden can fix America’s climate credibility

Joe Biden in the White House will represent a 180-degree pivot on climate change from his predecessor. But with control of the Senate down to a January runoff between both pairs of candidates in Georgia, it’s still too early to know how much world-saving will be on the table.

Joe Biden in the White House will represent a 180-degree pivot on climate change from his predecessor. But with control of the Senate down to a January runoff between both pairs of candidates in Georgia, it’s still too early to know how much world-saving will be on the table.

A full sweep for Democrats would open a world of possibilities for new climate legislation, including a national carbon tax, permanent tax breaks for wind and solar, and eliminating tax cuts for fossil fuels. But even if Republicans maintain the Senate, Biden still has some options.

Losing control of the Senate would “diminish or eliminate entirely the prospects for most decarbonization legislation,” according to a recent Bloomberg New Energy Finance report. It’d limit how much Biden can squeeze from the federal purse for his $2 trillion climate plan, and hamstring his ability to ratify the Kigali Amendment, a 2016 global treaty to reduce emissions of planet-warming hydrofluorocarbons. Executive orders and new regulations would be challenged in the courts, with a Supreme Court freshly primed to disfavor environmental regulation. Cabinet and judicial nominees would be harangued and possibly rejected; passing even basic legislation would be a grind.

And yet, this is familiar territory for Biden.

The Obama administration also faced Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell and his Republican-controlled Congress when it pushed through the Paris agreement and a host of related climate policies. Now again, the former vice president would need to rely on executive branch actions, which may be more vulnerable to legal challenges than bonafide laws but can come together more quickly.

Overall, the way Biden can pursue aggressive climate policy in uncertain political waters is to think beyond its traditional boundaries, cramming climate change mitigation and adaptation measures into every nook and cranny of the government.

First things first

Biden’s first action is likely to be rejoining the Paris agreement, which he could do on day one. That’s easy enough: just a signature and a 30 day waiting period.

But what comes after that—the specific policies the administration shows the world in order to meet its Paris goals—will make or break America’s climate credibility. “He can’t just say, ‘We’re going to pick up where we left off’,” said Andrew Light, a state department climate negotiator under Obama who is now a professor of public policy at George Mason University. “He has to do something really strong on climate out of the gate.”

The first stop will likely be a pandemic stimulus bill, which could offer support for clean energy jobs and R&D. This will be a first opportunity to see how much McConnell plans to let Biden get away with.

Other major legislation is sure to be contentious, but one strategy for Biden may be to tuck funding for clean energy or climate adaptation into bills for infrastructure, farms, housing, or other issues. He may also have a relatively easy time with tax breaks and research money for carbon capture technology, which, because it often facilitates oil production, tends to have bipartisan support.

But unless Democrats prevail in Georgia next year, the legislative branch won’t be the most effective venue for progress. Though Congress might be a pain, this time Biden will have the advantage of growing support for climate measures from the public and the business community—plus two other branches of government.

Beyond legislation

Leaving Congress out of the picture, Biden has said he plans to reverse some or all of Trump’s executive orders on climate, which mainly either relax pollution restrictions or open new land and water for drilling.

The president is also tasked with appointing positions to federal agencies. That means he could stack the executive branch with climate hawks—and not just in obvious positions like the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the departments of energy and the interior. Biden could target departments of commerce (which controls NOAA), agriculture (which, among other things, does much of the nation’s wildfire fighting), treasury (which could help the financial system reckon with and disclose climate risks). Transportation, state, homeland security, and housing and urban development positions can all be directed to identify ways they can either help cut the nation’s carbon footprint, or help Americans adapt to climate impacts.

Although any new regulations will doubtless face legal challenges from Republican-led states and industry groups, Biden could get creative with existing laws like the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act to draft new regulations on methane, carbon, and mercury emissions—plus other forms of fossil-related pollution, from drilling operations and the electricity sector. He could also enact more stringent emissions standards for vehicles and airlines, and support California or other states that want to go even further.

Meanwhile, executive orders, bully-pulpit prodding, and the commander-in-chief’s prerogative can go a long way without facing too many obstacles. Biden has said he plans to create a Justice Department office to investigate environmental injustice, an important issue for vice president-elect Kamala Harris, for one, and could add a White House office to coordinate cross-departmental climate issues.

Biden could re-calibrate the government’s “social cost of carbon” estimate and make sure it, plus the latest science and environmental and health “co-benefits,” are considered in permitting and regulatory decisions by the EPA and other offices. He can appoint a new chairperson of FERC, which oversees the nation’s electric grids, and encourage them to support state-led carbon pricing and beef up utility-scale renewable energy batteries and transmission lines. And he could fix the National Flood Insurance Program, starting by updating the maps it uses with the latest science.

The Department of Defense is another critical lever. Biden could direct the military to boost its spending on renewables, review the exposure of military installations to climate impacts, and prepare for scenarios in which water shortages, natural disasters, or mass migration could create national security risks for the US.

Foreign policy

That’s all within the country’s borders. But America’s climate leadership doesn’t simply hinge on setting an example—collaboration is key. Biden has planned to make climate change a centerpiece of his foreign policy, an arena in which a president has almost complete freedom.

He can start by re-engaging with the Arctic Council, which is working to curb methane from polar drilling operations. With some creative accounting, he could cough up the $2 billion America promised and never delivered to the UN-administered Green Climate Fund. He could make foreign trade deals contingent on emissions targets, a move France has recently played against the US.

The State Department could ink one-off deals with India to share clean energy technology, or with Canada and Mexico to set methane targets, while the US Agency for International Development combats climate-related food insecurity and poverty in developing countries. And Biden could work to restore the tattered reputation of the US as a country that negotiates in good faith and keeps its promises.

Unfortunately, the clock is ticking. Any measures Biden takes against fossil fuels could hurt the Democratic party in fossil fuel-reliant states like Pennsylvania, and risk fueling a backlash that could flip the House of Representatives to Republicans in 2022 and worsen the gridlock.

But the clock is also ticking fast for the global economy to reach net zero emissions by 2050. It’s time to throw everything at the wall.