In the run-up to the 2020 US presidential election, social media platforms unveiled a bevy of strategies for tamping down misinformation before and after the polls closed. While they appear to have done a decent job moderating English-language content, a torrent of misinformation has slipped through in Spanish.

As the New York Times reported yesterday, Spanish-language Facebook and Twitter accounts with large followings have repeatedly made false claims that US president Donald Trump has already won the election and that his challenger, Joe Biden, is attempting to steal the election.

“The platforms have done a pretty good job through yesterday on disinformation, when we think about the English-language content,” said Dipayan Ghosh, a former privacy and public policy advisor at Facebook who now heads Harvard’s digital platforms and democracy project. “But the fact that this is bubbling up in Spanish suggests that [Facebook] hasn’t done a good job thinking about the Spanish language in the election context.”

Ghosh said social media executives, and the US regulators who have the power to threaten their businesses, tend to speak English. And the algorithms and the human moderators tasked with detecting and slowing misinformation are most attuned to English-language content. “The content moderation practices at Facebook and other platforms are not nearly as sophisticated or robust in any language besides English,” he wrote in an email. The incident is another illustration of the language biases built into the AI algorithms that, among other things, help social media platforms spot harmful content.

Facebook, and its encrypted messaging app WhatsApp, have been particularly virulent vectors for Spanish-language misinformation this year. Politico’s Sabrina Rodríguez first reported on the wave of false information invading social media feeds in South Florida, where online conspiracy peddlers like YouTube-based Informativo G24 and Noticias 24 claimed, among other things, that Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro secretly controlled Black Lives Matter protests.

The story prompted members of Congress to call for an FBI investigation into Spanish-language disinformation, which never materialized. As Rodríguez explained on the news podcast El Hilo, the agency ultimately left it to the social media companies to police their own platforms for misinformation.

Facebook and YouTube did not immediately respond when asked how they’ve managed their disinformation policies across languages. A Twitter spokesperson said the company employs a dedicated team of specialists to monitor feeds in multiple languages, including Spanish.

US Latinos are not a monolith, but many Spanish-speaking communities are particularly at risk of falling prey to the kind of election misinformation now spreading across social media platforms, says Eduardo Gamarra, a political science professor and director of the Latino Public Opinion Forum at Florida International University. He points out that Cuban, Venezuelan, and Nicaraguan immigrants and their descendants have fled authoritarian left-wing regimes, and are primed to believe that Democrats are trying to steal the election.

“If you message a bunch of lies to a community that is not susceptible to those lies, the impact is minimal,” he said. “But if you transmit effective messages to a community that is very susceptible, the message is going to be effective.”

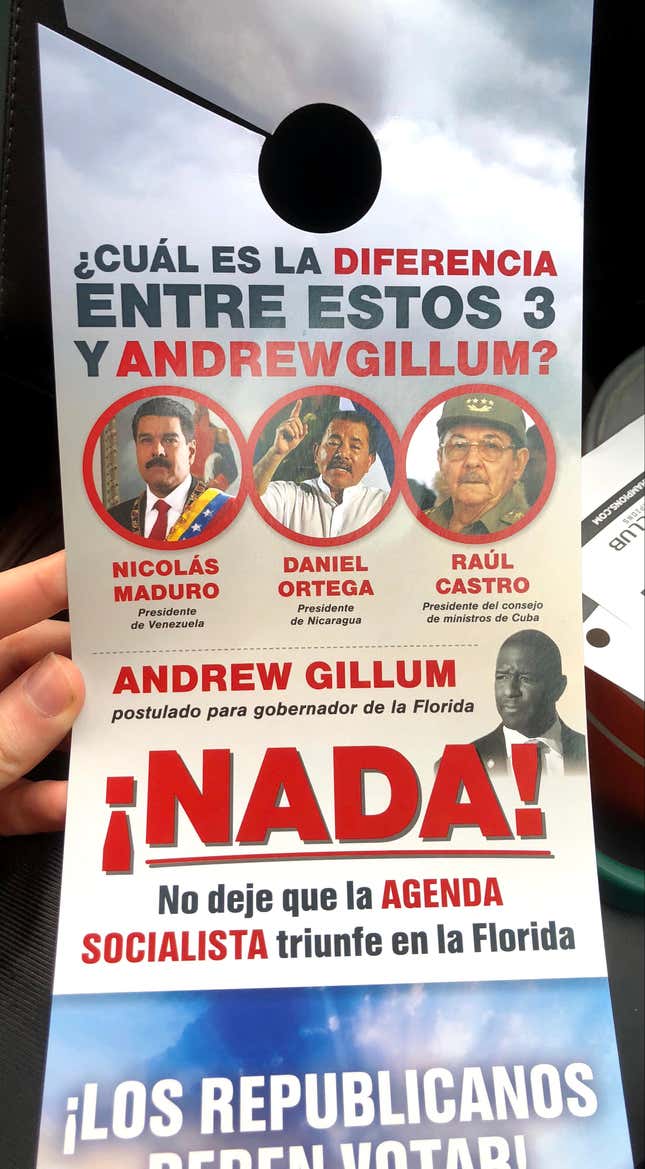

Partisans have spent decades targeting Cuban-Americans, and more recently Venezuelan- and Nicaraguan-Americans, with messaging on local radio stations and direct mail campaigns directly equating Democrat candidates with Latin American dictators. Now, thanks to a breakdown in content moderation, that messaging has spread onto social media.

“We have the additional ability to share craziness that was only limited to Spanish radio before,” said Maribel Balbin, who heads Miami-Dade County’s chapter of the League of Women Voters. She said social media has created new avenues for disinformation as well: Conspiracy theories that get debunked in English, she said, get a new lease on life when they’re translated into Spanish.

“There are a lot more people who are reading English messaging that can tell people, ‘This story just isn’t true,’” Balbin said. But, she says, there are fewer fact-checkers and media literacy guides available in Spanish. “People reading this stuff in Spanish have fewer resources behind them to realize this is misinformation.”