For the last 100 years, water in the American west has rarely been priced on the open market. Water rights were bought and sold through private contracts and government deeds, and public agencies doled out most of the coveted commodity. As Marc Reisner wrote in Cadillac Desert, the seminal 1993 book on the region’s water woes: “In the West, it is said, water flows uphill toward money.”

But on Dec. 7, trading began in the first futures market for water. Farmers, businesses, and investors can now pay to lock in the future price of water in California. According to Veles Water, a financial services firm focused on water, the first day of trading saw two buyers secure prices for about 650,000 gallons of water—enough to cover about 15 football fields about one foot deep.

Nasdaq already lists spot water prices on its NQH20 index. But the new exchange was looking for a way to “determine the fair value of water as a commodity,” giving buyers a way to hedge against the risk of droughts. It teamed up with Veles Water and West Water Research, a consulting firm in water trading, to allow trading through CME Group, a derivatives marketplace.

In spite of its modest size, the futures market—which buys investors the right to purchase water at a specific price on a future date like oil, corn, and other commodities—is likely to become a benchmark indicator of water stress in the region. As climate change alters how much water is available and who receives it, markets like these will govern more and more of one of the most sought-after commodities for arid regions.

In theory, this will ease the financial crunch for farmers and other businesses that need insurance against wild price swings. (Unlike some commodities, water futures don’t require the buyer to take physical delivery since water distribution is highly regional, as are the regulations.) “Basically, it’s a tool to reduce price risk,” says Lance Coogan, CEO of Veles Water. “It brings price transparency and it’s an excellent financial hedge when the underlying price can go up 10 times.”

For now, the market just covers California. But the need to hedge the price of water is likely to expand.

In a study of how water stress will affect the creditworthiness of companies, a major US bank found its default losses would likely rise by a factor of 10. Regional and community banks were even more vulnerable, especially in the midwest, where lenders reported 70% of their customers suffered from extreme weather events in 2019. Rostin Behnam, of the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission responsible for US derivatives markets, said water price futures will be crucial to managing climate risk for businesses and investors, according to the Financial Times.

That’s driving wild fluctuations in the price of water. From 2011 to 2015, California endured its worst drought since record-keeping began in 1895, and “we saw prices I thought we’d never see,” says Clay Landry of WestWater Research. Prices rose above $2,000 per acre-foot, roughly four times the historical price on the index.

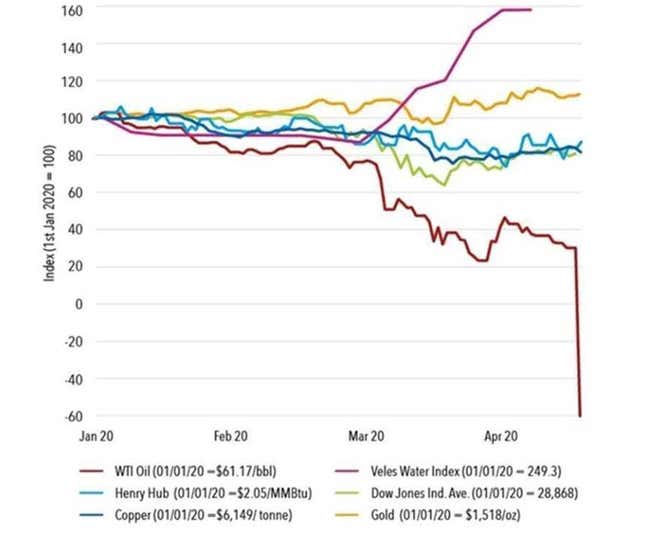

Volatility returned in 2020, as worries grew about another dry year. In mid-April, the spot price on the Veles Water Index (an aggregate of prices across numerous private transactions) spiked 160% above January prices. A futures contract would have allowed market participants to lock in that January price, avoiding volatility.

The futures markets for water, argues Landry, will better reveal how water should be priced in an increasingly uncertain world. People are already responding to this price signal: Housing projects are using desert-adapted landscaping and farmers have adopted new irrigation and agricultural practices.

“We are starting to see more extreme events from very very dry years to very wet years,” says Landry. “I think, increasingly, people are recognizing that volatility.”