The great paradox of the vaccines for Covid-19 is that they simultaneously demonstrate that vaccines are lifesaving and necessary, while opening a possible gateway for vaccine skepticism.

Even people who trusted vaccinations before might be taken aback by a rapid development timeline that has led them to doubt its safety.

Globally, only about 46% of people said that they would take the Covid-19 vaccine without reservations, according to an October survey published by Ipsos. In France and Japan, only 18% of respondents say they would have no hesitations being vaccinated; in Spain, 25% say the same, in Italy it’s 26%, and in Germany, 32%.

In order to deal with this skepticism, beyond large government awareness campaigns—and before resorting to making vaccines mandatory—health professionals are trying to educate their patients, reassuring them of the safety of the vaccines.

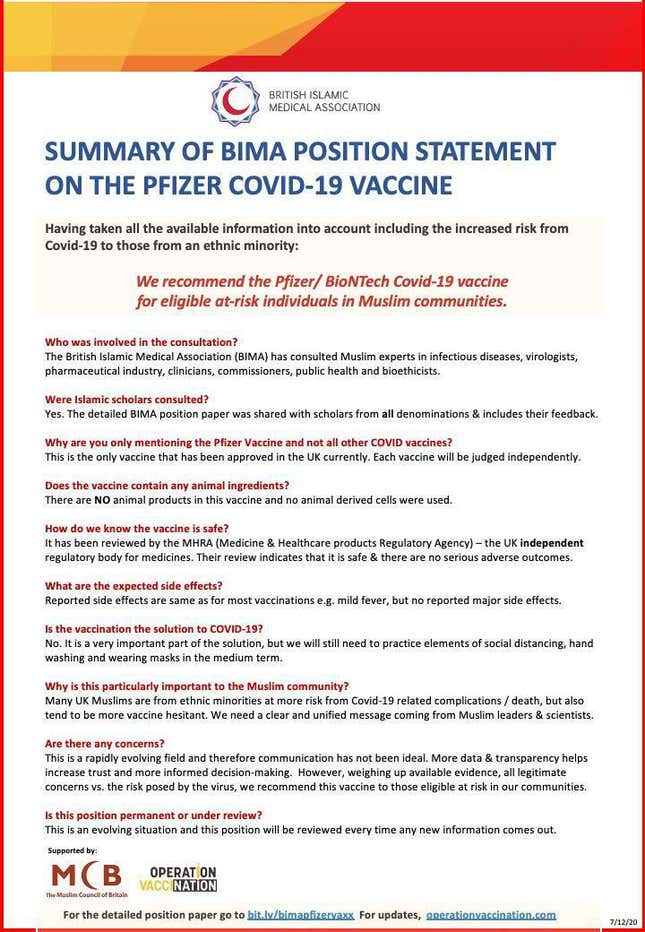

But any one-size-fits-all strategy can struggle to engage patients of different communities and backgrounds. Aware of this, the British Muslim Medical Association (BIMA) published a statement that doesn’t simply answer general questions about the vaccines but gets into any issues that are specific to the Muslim faith.

The statement begins by clarifying that Muslim doctors were involved in the decision of recommending the Pfizer-BioNTech Covid-19 vaccine, and that Islamic scholars were consulted, too. The document highlights, too the vulnerability of the UK Muslim community, which like other minorities has been hit especially hard by Covid-19.

Salman Waqar, a physician and researcher at Oxford who has long been a community organizer and serves as general secretary at BIMA, says the community-specific messaging is necessary for all marginalized groups, which as a result of being discriminated against in the past are often less likely to listen to assurances coming from the mainstream.

Other religious communities in Britain—including Jews, Sikh, Hindus, and Black Christians—also delivered targeted messages through the pandemic, says Waqar. The UK’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies has recognized the relevance of ethnic subgroups in Covid-19 communications, and research has shown a specific advantage to adopting a faith-based perspective for coronavirus outreach.

But this isn’t true just of ethnic or faith minorities, says Waqar. The LGBTQ community, the disabled community, and members of the white working class, all of whom also experience a sense of being left out by the system, would also benefit from a similar approach.

This kind of initiative also shows how important it is to have an inclusive healthcare workforce, because members of a community will be more ready to respond to the reassurances of those who belong to it, too.

“The problem is not the message, it’s the messenger,” says Waqar. When it comes to BIMA, for instance, its members are health professionals but are also active members of the community. This connection helps BIMA promote scientific messages, and avoid the risk of anti-vaccine sentiment, which has stronger among vulnerable groups.

But while in the short term this approach is effective, Waqar adds that “the long-term solution is to reduce the inequality, so that [these groups] consume and trust mainstream messages.”