The first thing to know about page 132 of the Pfizer vaccine report is that it doesn’t exist.

Or rather it does, but it contains just a few rows of abbreviations included in Pfizer’s clinical trial protocol for the Covid-19 vaccine invented by BioNTech. The version of page 132 circulating on corners of the internet—which doubts the Pfizer vaccine’s safety specifically for pregnant people— is not from Pfizer’s report. It’s a screenshot from a pdf of the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) guidance for healthcare professionals. (You can find the HTML here and the pdf version here).

In the actual Pfizer study protocols, p.123-126 cover people of childbearing age. However, they don’t outline risks to fertility: They detail protocols Pfizer took to ensure that no one in the trial became pregnant, or contributed to a pregnancy, because that wasn’t the intent of its study. Pfizer didn’t want to include anyone expecting in that clinical trial; at that stage in the studying the new Covid-19 vaccine, it’d be unethical to do so.

The words of warning around the screenshots of these documents—that the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine causes widespread “infertility” and “birth defects due to genetic manipulation”—are false. There is no evidence to support those claims. Facebook, to its credit, has flagged at least one of these wide-reaching posts as misinformation. What the screenshots do highlight is the fact that there are still unanswered research questions about Covid-19 vaccines, even though governments have given them a cautious green light. It’s a perfect example of what scientists know and don’t know about the newly authorized Covid-19 vaccines.

It’s perfectly normal—and even encouraged—to have questions about a new vaccine, especially when it’ll likely reach you and 7 billion of your closest friends. Quartz is here to break down these concerns.

What does the Pfizer study protocol say about people who could become pregnant or contribute to a pregnancy?

The protocols say that people who make sperm can be included in the clinical trial if they agree to abstain from heterosexual sex for a month after their final dose or use a condom, and not to donate sperm for that time.

It also states that people who could become pregnant can participate if they agree to abstain from heterosexual sex or are using a list of approved birth controls (which includes everything but the pull-out or rhythm method). Healthcare professionals conducting the clinical trial are advised to screen anyone who could become pregnant about their sexual activity and last periods to rule out an undetected early pregnancy. Pfizer states that the reason for these precautions is to “eliminate reproductive safety risk of the study intervention”—which translates to avoiding any possible risk in the absence of concrete data assuring the vaccine’s safety for pregnant people.

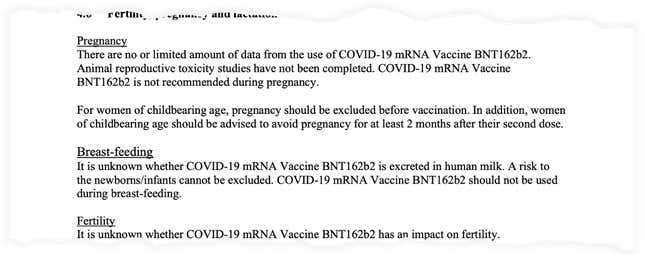

What does the UK’s MHRA say about Covid-19 vaccines and fertility?

In its guidance to healthcare providers administering vaccines, the MHRA states that the Pfizer/BioNTech’s Covid-19 vaccine long-term effects on pregnancy and fertility hasn’t been studied extensively.

These guidelines recommend that healthcare providers ensure that the people they vaccinate aren’t pregnant, and that they should not try to become pregnant up to two months after their second dose. This is not because the vaccine is suspected to be dangerous—it’s because there isn’t data supporting that it’s perfectly safe. Pregnancy already takes a massive toll on the body, and healthcare providers want to make absolutely sure they’re not adding to that in any way.

It also states that, because scientists aren’t sure if the vaccine can be secreted in breastmilk, nor if its safe in infants, people who are breastfeeding should abstain from getting the vaccine.

And it states, in plain language, that scientists don’t know if fertility can be impacted by the vaccine. That doesn’t mean, however, that it is inherently dangerous for fertility.

What data do we have around pregnancy from the Pfizer/BioNTech trials?

In the Phase 3 trial data that Pfizer/BioNTech submitted (pdf, p. 42) to global regulatory authorities, the companies explicitly stated that they did not intend to test the vaccine on pregnant people. This is because it’s generally considered unethical to include pregnant people in clinical trials—at least at first.

In the trial, researchers required people who could be pregnant to take a quick pregnancy test; if it came up positive, they were not allowed to participate in the trial. Still, Pfizer and BioNTech report that 23 people became pregnant over the course of their trial; 12 of them received the vaccine, and 11 of them received the placebo. Two people suffered miscarriages, but both of them had received the placebo and not the vaccine. Twelve data points of pregnant people with the vaccine isn’t enough for scientists to say whether or not it’s safe for all pregnant people.

The review memo from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granting the vaccine emergency use authorization in the US states (pdf p. 45) that Pfizer plans to conduct another clinical trial on pregnant people in the future. It also plans to continue a surveillance studies in general populations to assess its vaccine’s long-term safety.

Although we don’t have long-term data yet on vaccine’s safety for any group, previous studies have shown that mRNA (from ourselves, and from vaccines) breaks down within hours, which suggests that it likely won’t have any long-term effects. As a reminder, mRNA a vaccines cannot alter your own genetic material.

Why didn’t the companies study effects on fertility?

The primary endpoint of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine trials were to see if their vaccine candidates were safe for participants and effective at preventing cases of Covid-19, which is the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2. Importantly, they were not looking at whether the vaccine did other things, like prevent SARS-CoV-2 transmission entirely (which would be great!) or have other kinds of long-term effects on fertility.

These studies were designed to get an effective vaccine out to the public as fast as possible. This doesn’t mean that regulators cut corners. As Quartz’ has reported before, global authorities resisted pressure to speed up the review timeline, knowing that people would be skeptical of a rushed trial. The vaccine’s effects on fertility—and other long-term questions—will be answered in ongoing surveillance studies, although scientists do not have reason to believe that could be going to be dangerous adverse events down the road.

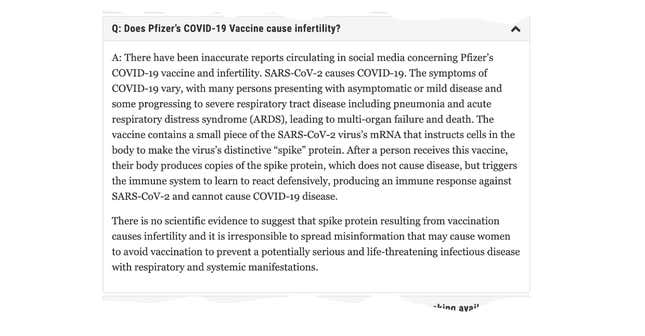

Are the UK’s guidelines different from what the US Food and Drug Administration says?

Yes and no. The FDA is working with the same data as the MHRA, but has framed some of its answers to common questions about the Pfizer/BioNTech slightly differently.

In the same absence of concrete safety data for fertility and pregnancy, the US FDA has stated that although we don’t know if the vaccine could cause infertility, we also have no reason to believe that it could. It explains that mRNA vaccines do not contain the actual SARS-CoV-2 virus, nor any part of it, which is why it cannot impact fertility.

It then goes on to say that anyone spreading misinformation about the vaccine’s negative impacts on fertility is irresponsible, because they would be discouraging others from getting protection for a potentially life-threatening disease.

So is the vaccine safe for people who are pregnant? Or people who want to become pregnant?

As Quartz has reported before, no group recommends that people who are pregnant get the Covid-19 vaccine. However, in the US, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and other groups have advocated that people who are pregnant should be able to access a Covid-19 if they want it. They also recommend that these individuals talk to their healthcare providers about whether the vaccine is right for them, given their other underlying health issues or lifestyles.

In the US, the lack of concrete evidence in favor of the vaccines’ safety in pregnant people, and lack of concrete concerns, are taken to mean that the risk is not great enough to avoid vaccination at all. In the UK, not knowing for sure is deemed too great a risk to take on. Neither is a wrong approach—they’re just different. What’s important is that we all understand how each group came to these stances, and for you to be able to determine which level of risk you and your healthcare providers are most comfortable with.

Update (Dec. 31): This story has been updated to reflect p. 123-126 of the Pfizer report, which focus on trial participants of childbearing age.