The year 2020 broke disaster records across the country in destructive and expensive ways. The Atlantic had so many hurricanes, meteorologists ran out of tropical storm names for only the second time. Across the Midwest, extreme storms flattened crops and tore up buildings. Western states repeatedly broke records for their largest wildfires on record. Globally, it was tied for the hottest year on record.

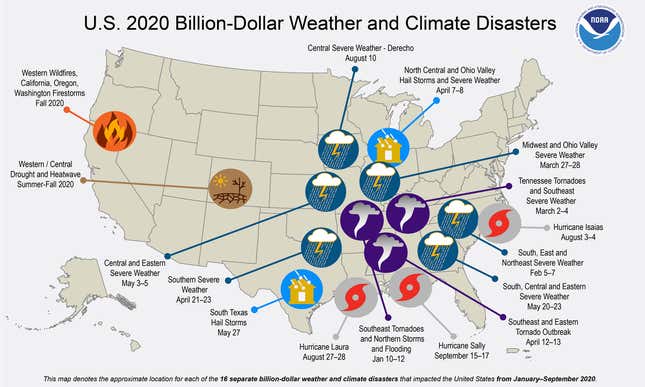

All told, in 2020 the US had 22 billion-dollar weather and climate disasters, six more than any previous year, NOAA announced on Jan. 8. Such disasters affect millions of Americans and are particularly devastating for low-income communities and communities of color. They destroy homes, schools, and businesses. They put lives at risk.

Families, communities, and taxpayers are paying the price, yet many of these losses could be avoided with smart policies.

For example, the National Institute of Building Sciences estimates that updating and improving building codes alone could save $4 for every $1 spent and create 87,000 new jobs. Similarly, reforming land use and zoning rules can help avoid putting families at risk. An estimated 41 million Americans currently live in homes at risk of flooding and millions more are at risk from wildfires.

And yet, these actions are rarely taken. Local governments—which have authority over zoning and building codes—have a strong financial incentive to keep on building, even in risky places. The federal government—which has the greatest financial incentive to prevent damage before it occurs—has little to no authority over building codes or land use.

Federal policy can, however, incentivize local governments to use their authority to reduce risk. A new federal administration that is attuned to the growing risks created by global warming could take advantage of that influence.

We are disaster scientists—engineers and policy researchers who study how to prevent or reduce disasters. We recently published suggestions for how the new administration can reform US disaster policy. If done right, modern disaster policy would endorse development that accounts for risk, promote climate-proof investments in infrastructure, advance social justice, and protect society’s most vulnerable populations.

Here are four key reforms that could get bipartisan support, reduce federal spending, and protect American lives.

Get a better grip on how disaster money is spent

Without careful oversight, disaster funds can end up being spent on ineffective projects or not spent at all.

For example, the Department of Housing and Urban Development is a major source of disaster funding, but the precise amount it spends and how has sometimes been a mystery. Following the hurricanes of 2017 and 2018, HUD received more disaster funding to distribute than any other agency, but by 2019 less than 1% had been spent. It took more than two years for HUD to approve disaster relief spending after the 2018 California fires. The Government Accountability Office concluded that HUD needed better oversight of how funds are spent and more staff, and the Congressional Research Office has suggested that Congress may wish to consider limits on federal disaster relief spending.

Disaster spending is notoriously difficult to track because, although the Federal Emergency Management Agency is the nation’s central disaster authority, almost every federal agency administers some level of disaster funding and disaster funds are often mixed with other programs. This all makes it difficult to hold agencies accountable.

That said, increased oversight, including audits by the GAO, improved record-keeping, making records publicly accessible and consistently measuring whether funded projects build resilience could help turn this around.

Get everyone on the same page

Reducing risk often requires the work of multiple federal agencies, but if agency actions are not coordinated, they can create complications, duplications, and waste.

For example, the US Army Corps of Engineers is building a seawall on New York’s Staten Island based on a calculation that the wall would protect homes—but some of those homes have since been removed by a FEMA and HUD project.

FEMA and HUD both fund property acquisitions to support flood risk reduction, but their funding programs work on different timelines, which can complicate local officials’ efforts.

Numerous other agencies are also involved in risk reduction and recovery. The Small Business Administration gives out loans. The Department of Education funds the reopening of schools. The Department of Transportation funds repairs for roads and bridges. The efforts of these agencies and more need to be coordinated to build resilient communities.

The new administration could order interagency task forces to define clear roles for each agency, establish methods for coordination, and create long-term plans for national resilience.

Change state and local government incentives

State and local governments might be more inclined to take steps to protect communities from disasters if they had to pay for a larger share of the aftermath.

When public buildings and infrastructure are damaged in a disaster, the federal government will pay for 75% of the recovery cost if the damage exceeds a certain threshold. The idea is for federal assistance to kick in when state and local governments are overwhelmed. However, that threshold is just US$1 million plus $1.55 per person in the state—an extremely low threshold.

FEMA is attempting to raise these thresholds, but the increase may not go far enough and is unlikely to be sufficient on its own.

In 2016, FEMA proposed a “disaster deductible” that would make states responsible for a deductible, between $1 million and $53 million, proportional to their hazard risk and resources before federal money would become available. States could earn credits to reduce their deductible by taking risk reduction measures like enforcing building codes or investing in insurance or emergency management programs—just like a safe driver discount for taking a safe driving course. Without leadership, the program lost momentum, but the new administration could improve disaster policy by revisiting this idea.

Local communities could also be encouraged to reduce their risks if Congress amended the National Flood Insurance Program. The program is bankrupt because its rates are too low to cover its costs and not enough people are participating.

Reforming this program will not be easy. If insurance rates rise, low-income residents won’t be able to afford insurance or may choose not to carry it at all, leaving them even more vulnerable to the next flood. Congress knows the program is struggling, which is why instead of reauthorizing it permanently, the program has been temporarily reauthorized 16 times over the last three years.

In essence, this kicks the problem down the road without solving it. Instead, the new administration could prioritize finding a long-term solution.

Put the focus on people

Disaster funding increases the gap between rich and poor because it seeks to make people “whole”—to replace what they had before the disaster. Those who had more get more help; those who had less get less. This, despite the fact that wealthy people are more likely to have assets they can draw on to recover, like a job with paid leave and savings to afford safe temporary housing.

Disaster response needs to take historic injustice into account.

A community that has faced disinvestment, redlining, or other forms of injustice often has infrastructure that is more vulnerable to hazards and needs additional support, not less. Ten percent of government-subsidized housing is in floodplains, which puts the residents at greater risk. Addressing underlying vulnerabilities will require coordination among numerous federal agencies and state and local governments.

Achieving effective disaster policy will not be simple. The work begins with Congress and the president making disaster reform a top priority. An executive order in the first 100 days that mandates coordination, reform, and consideration of climate change and social equity would be a good first step toward a safer, more resilient nation.

A.R. Siders, Assistant Professor, Disaster Research Center, University of Delaware; Allison Reilly, Assistant Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Maryland, and Deb Niemeier, Clark Distinguished Chair and Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Maryland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.