Many China-watchers are worried that China is beginning to tip over the edge of a big drop in housing values—and that falling prices could give way to a crash. As we discussed yesterday, it’s hard to tell what the supply and demand for housing actually is. Plus, smaller cities differ dramatically from larger ones, as the chart below shows.

If home values do drop, it will be very hard on middle-class households—something highlighted by a recent study on household financial assets by researchers from Southwest University of Finance and Economics in Chengdu, via Caixin. It will also have ominous implications for the overall economy and for the Chinese government’s reforms.

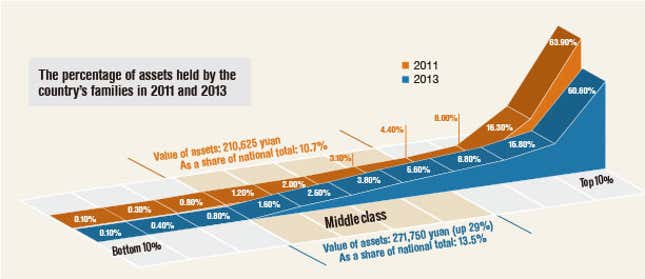

Between 2011 and 2013, the value of the middle-class’s assets jumped nearly 30%, to 271,750 yuan ($43,750) on average. A greater share of overall wealth has shifted to the middle-class—closing the gap between China’s haves and its have-nots.

That should be great news, not just for middle-class households but for the Chinese economy too. A crazily low proportion of China’s GDP comes from consumption—less than 36%, compared with a global average of around 60%. To wean itself off its dangerous debt addiction, China needs its middle class to spend. The government has been trying to encourage that for a while, but it hasn’t worked. Why? Income inequality—with its concentration of income at the higher end—strangles overall consumption, as economists such as Michael Pettis argue, since wealthy households simply spend a smaller share of their income than ordinary households. And of course, there are vastly more ordinary households than wealthy ones.

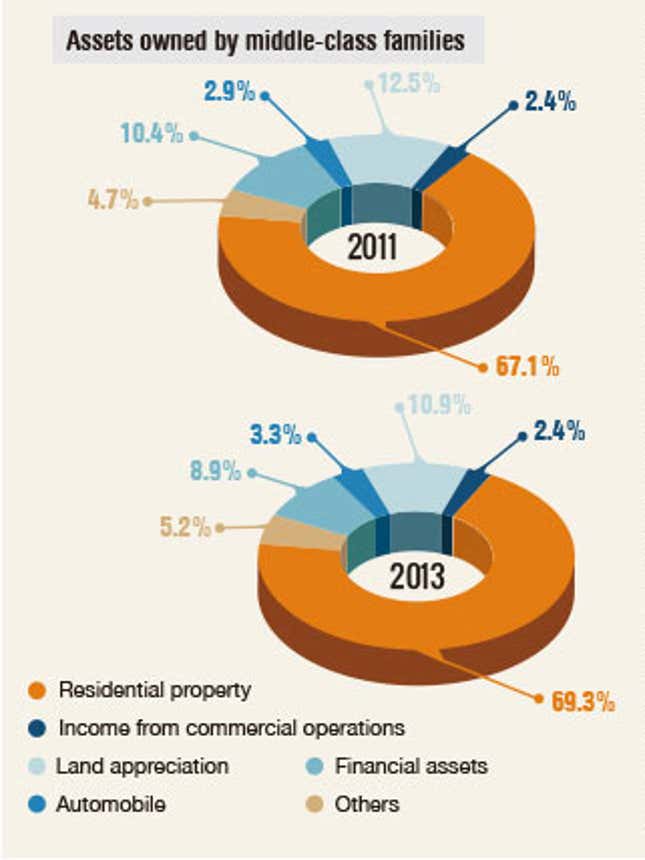

Most of that new middle-class wealth—at least on paper—comes from soaring home values, especially in relatively wealthier cities. For instance, 83.8% of the total assets (link in Chinese) of average Beijing residents came from their homes, compared with the national urban average of 66%.

This doesn’t affect rich families as much. They own enough other stuff—a lot of it probably overseas—that they don’t depend nearly as much on Chinese property appreciation to boost their net worth. That means middle-income families stand to suffer much more if the housing market plunges—and when their consumption declines, it has a bigger impact on the economy.

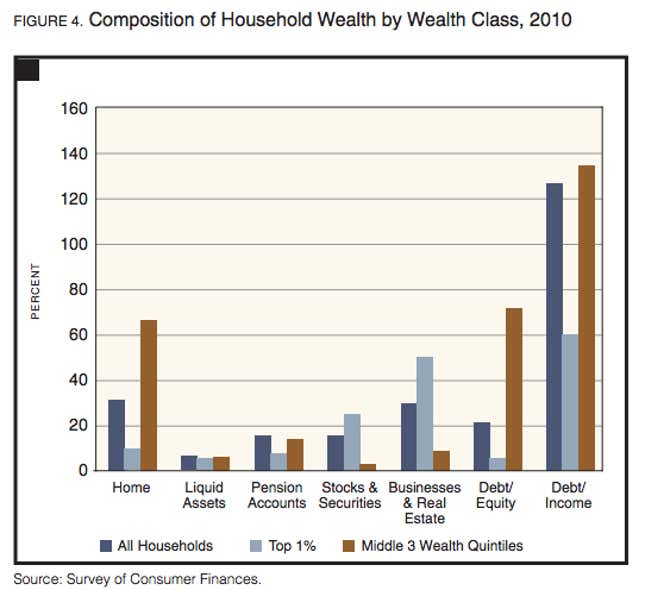

That’s pretty much what happened not so long ago in the US. Among middle-class American families, home values made up two-thirds of their wealth (pdf) in 2010 (three years after the housing market tanked) compared with just 9% for the richest households.

Average US household consumption grew at only 2% annually (pdf, p.3) during the four years after the 2007-8 crash, compared with a 4-5% average in preceding decades.

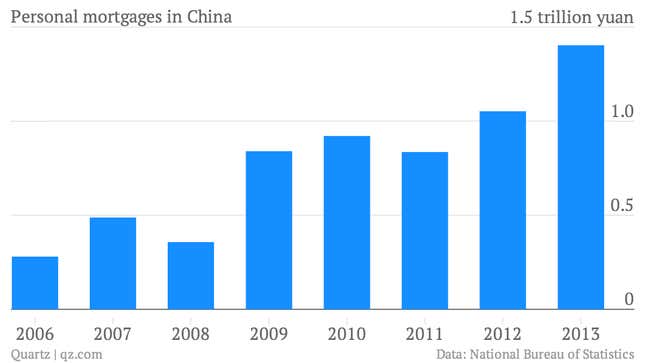

Of course, there are some big differences between the US and China. Middle-class America was saddled with hefty mortgage debt, which meant people had to pay steep mortgages instead of buying things. Chinese families aren’t nearly as leveraged, though that’s been changing:

Due to both China’s highly speculative stock market and its closed capital account, Chinese households have far fewer things to invest in than Americans do—which explains why the latter hold more stocks. Without income-generating investments, Chinese middle-class households will be even more sensitive to a drop in home values. And if the lack of ways to preserve their wealth makes them feel poorer, a collapse could also make them shovel still more money into wealth management products and high-yield shadow finance products—also not a great thing for the economy.