For years, Southwest Airlines has celebrated its differences with other airlines, starting with the way it treats its people. Founder Herb Kelleher emphasized it as the secret of the company’s success.

Famously, the company has never cut jobs or wages. On the customer side, it resisted bag fees, seated on a first-come first-serve basis, and offered affordable flights, all while remaining consistently profitable.

But the company is now facing major labor conflict for the first time in its history, asking its workers for what The Wall Street Journal calls (paywall) “some of the biggest contract changes” ever seen at Southwest in an attempt to cut costs. Management wants to tighten rules on sick time, freeze (though not cut) compensation for some, and significantly increase the part-time component of the workforce.

Union leaders are not happy. Both The Wall Street Journal (paywall) and The Guardian found employees who miss Herb Kelleher’s extremely personal management style, and the feeling that the company’s success was tied to their own. ”Ever since Herb…left, this has been more of a corporation and less of a family,” Union representative Randy Barnes told The Journal. (paywall) Kelleher stepped down as CEO in 2001 and chairman in 2008. He remained a full time employee through 2013 in a diminished role.

And other changes are coming. CEO Gary Kelly has said bag fees are on the table, and that international service will begin soon. Fares are up by 21% since 2008; larger competitors saw single digit increases during that period.

The pressure to cut costs comes from several sources: The company’s growth away from its budget-airline model; increased competition from other lower end carriers, newer entrants like JetBlue; and the fact that larger airlines have consolidated so massively.

But labor cost is a big part of it, despite good relative financial performance. The company has been dedicated to giving people long careers at the company, and shares profits with employees—average compensation including benefits was nearly $100,000 in 2012. Senior people tend to stick around and make a lot of money, and while other airlines have used bankruptcies and restructuring to invalidate expensive labor contracts, Southwest hasn’t done that.

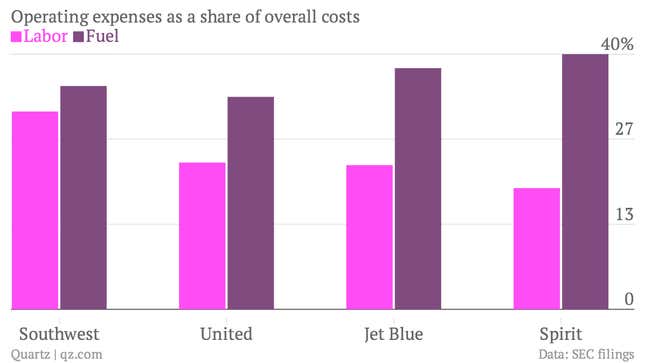

The result of those policies is that the company pays more for labor as a percentage of costs than its competitors. It pays a higher rate than industry giant, United; low-cost competitor Spirit Airlines; and JetBLue, which is fighting for its base of middle class customers. When it comes to fuel, Southwest’s costs are close to or exceeds its peers.

In the past, the company managed its higher labor costs by having an especially effective workforce, flying short routes, and by only using one type of aircraft. But now the company’s growth means it is competing for longer routes that require more people to work longer shifts. So much of Southwest’s labor force—over 80%—is unionized, and the company has a harder time ramping up to respond to demand because it has comparatively few part time workers to fill gaps or accept flexible schedules.

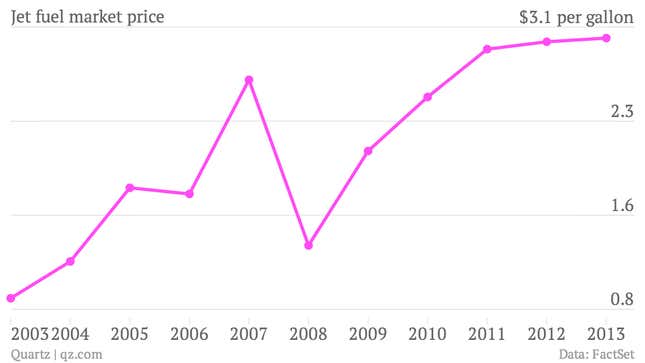

Fuel costs have also significantly increased, contributing to the changes that have stressed the company’s labor policies: Using fuel more efficiently means purchasing larger planes, competing in bigger markets, and flying longer routes.

Southwest still has a strong brand identity and plenty of consumer goodwill. But it might be losing some of that goodwill from its own workers.