Tracking every possible personal data point is a rising trend, and we have an increasing number of tools to help us “quantify” ourselves. But for now, their uses are mostly pretty frivolous: Fitness trackers feel like glorified pedometers, calorie and caffeine trackers like sophisticated food diaries. But the makers of quantification gadgets and apps could be missing a major opportunity: Contraception.

For women who want to avoid hormonal birth control, the current options are limited. They can choose a non-hormonal IUD or use barrier methods, but many rely on the old-fashioned “rhythm method” to keep tabs on when in the month they are ovulating, and can get pregnant. Al Jazeera America reports that the rhythm method, referenced as early as the year 388, is seeing a resurgence—and is now known as the “fertility-awareness based method” (FAM). FAM users chart their basal body temperatures, the appearance of their cervical mucus, and other bodily indicators in order to pinpoint their precise window of fertility.

The thing is, traditional rhythm methods can be tricky to use properly. A study headed by Lina Guzman, co-director for reproductive health and family formation at the research center Child Trends, suggested that many who rely on FAM may not be using it effectively (paywall). Of the 58 black and Latina women surveyed who used FAM as their primary birth control method, only a little over half were accurately tracking their fertile periods.

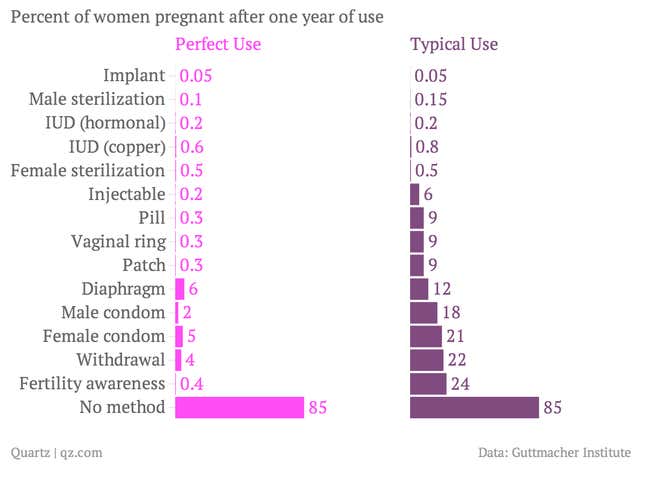

FAM has the biggest gap between “perfect” and “actual” use effectiveness of any modern method, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a non-profit that advocates for reproductive health and abortion rights:

Much of that gap closes when women track their fertility correctly. But that’s a challenge for anyone that doesn’t have a lot of time, support and resources at hand. For FAM to be effective, one must accurately assess cervical fluid throughout the day and take a very precise temperature reading at a consistent daily interval. Women also need partners who are supportive of their contraceptive practices, as abstinence (or a condom) is crucial during fertile periods. Women using FAM were self-quantifying long before it became a buzzword, but most of their tracking has been manual.

Technological aids can help, according to another recent study headed by Richard J. Fehring, professor emeritus at Marqutte University College of Nursing. In his study, women found that an online FAM helper—one with instructions and downloadable charting systems—improved the method’s effectiveness (paywall).

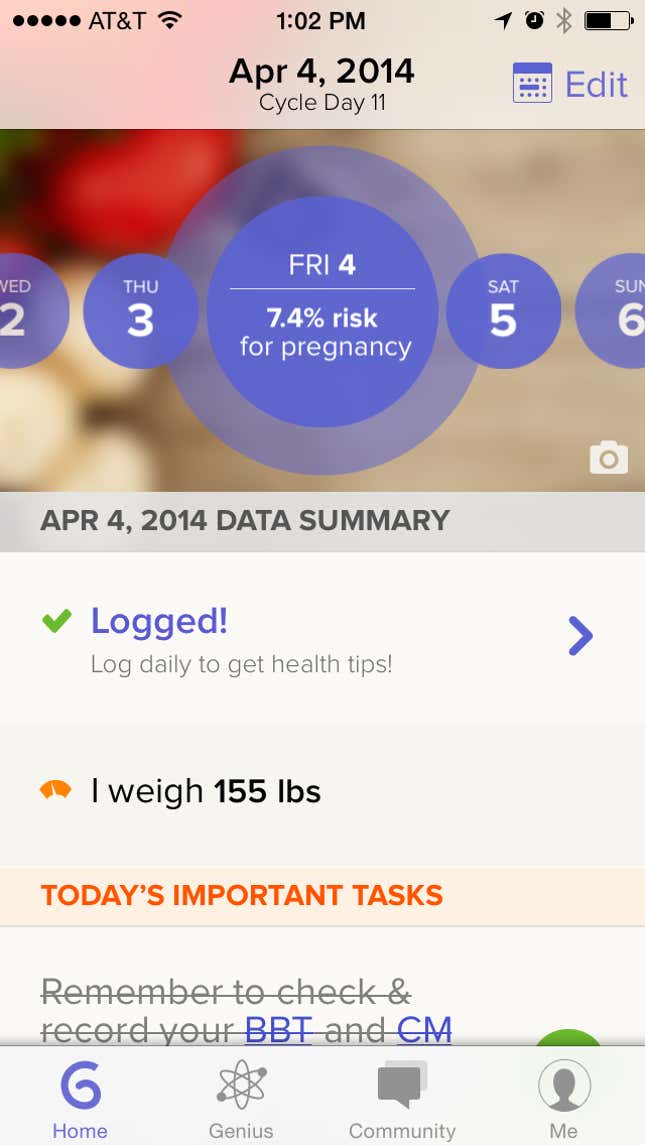

FAM users would be an obvious niche for app developers to target. To some degree, they already do: Lots of menstrual cycle trackers estimate fertility, though without much accuracy. And Glow, an app originally intended to aid conception, now has a setting for those endeavoring to avoid it: Women can record their fertility-related data points and see an estimate for their “risk” of pregnancy each day (instead of their “chance” of getting pregnant, for those seeking that outcome).

Glow has taken a step towards the passive tracking of fertility by allowing women to pair their fitness trackers to the app, letting them track their caloric intake and physical activity. This just contributes to the app’s growing body of data on conception: In time, the company may develop insight into what kinds of diet and activities help women conceive (or not).

But other devices on the market—the Scanadu, for example, which packs a suite of medical tests into a small scanner—could make the method even easier to use, and more effective. If Scanadu or a device like it offered quick-and-easy temperature readings (the Basis fitness tracker already does) and urine analysis (which can very accurately predict ovulation), FAM could come closer to competing with the convenience of a daily pill. And as the room for human error disappears, the accuracy—and popularity—of FAM can only improve.