A new corporate principle is: Never say you’re restating anything. The machines will hold it against you.

Over the past decade, “restatement” is the word companies have most strenuously tried to avoid in the text of their filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission, according to an upcoming paper by academics at Georgia State University’s J. Mack Robinson College of Business and Columbia Business School. The evasion is a response to the army of bots that investors routinely deploy to catch any whiff of implicit market intelligence. The bots flag “restatement” as a negative word, which darkens their outlook on a company’s prospects.

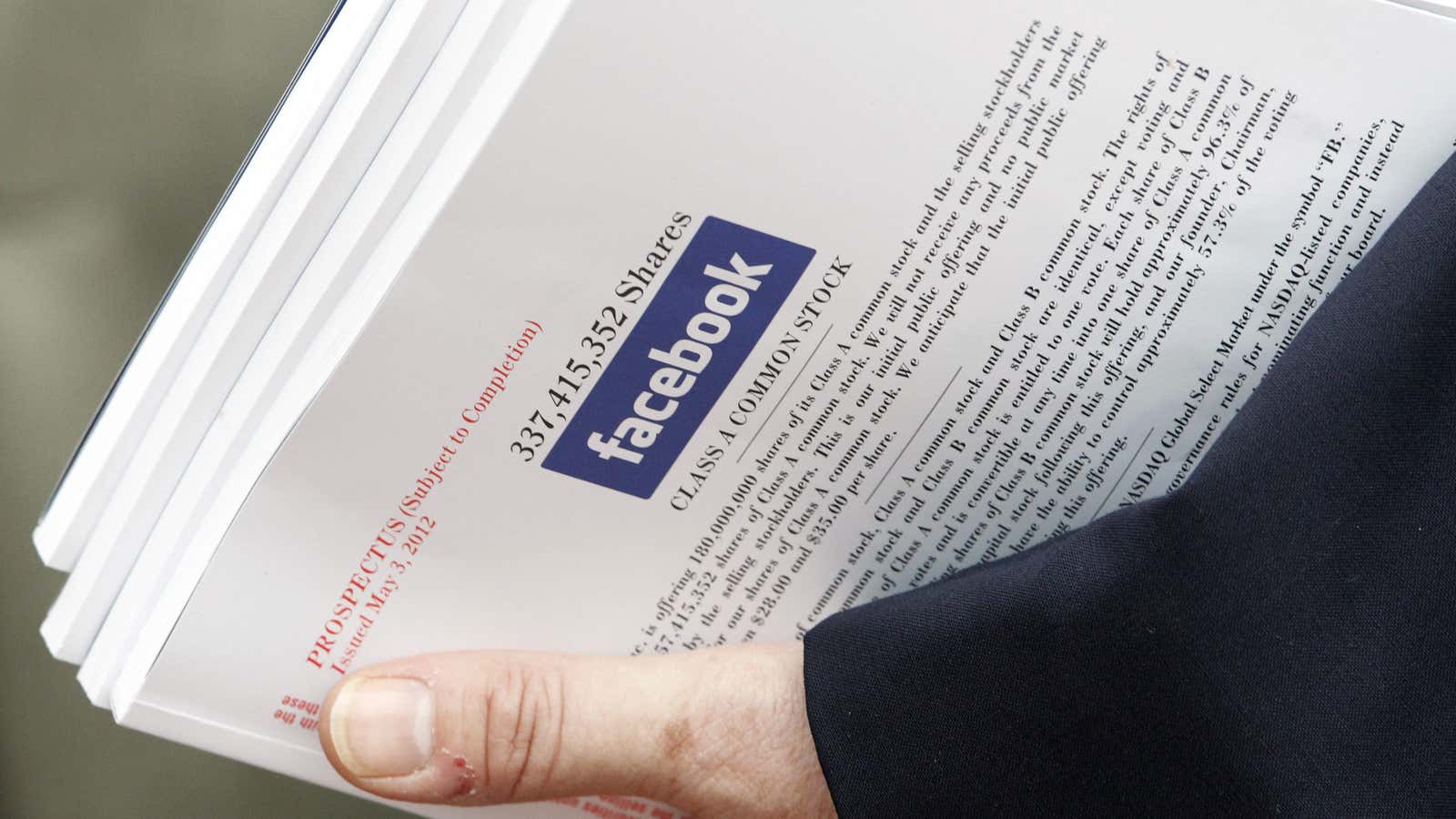

The paper, which builds on an earlier version released last October by the National Bureau of Economic Research, analyzes nearly 360,000 10-K and 10-Q documents filed with the SEC between 2003 and 2016. It shows how companies are trying to phase out words that, like “restatement,” are judged to have negative connotations by financial analysis algorithms. “Corporate disclosures and reporting have been reshaped by machine readership,” Baozhang Yang, one of the paper’s authors, said.

The dog-eat-dog nature of markets has always tended to favor those with an extra sliver of information. When everyone has access to the same, structured sources of data—published reports, earnings figures, profit-and-loss statements—the appetite for alternative data, of even the least merit, can turn very keen. Sometimes analysts and investors try to latch on to such alternative data using their own intuition. Nils Paellmann, a former vice-president for investor relations at T-Mobile, recalled how, on one earnings call, the company’s CEO—known for cursing freely and often—was far less profane than usual. “I got a lot of calls from investors, asking: ‘What’s wrong? Why wasn’t he his usual self? Is he less confident about the company’s outlook?’”

But the real thrust has come with the advance of automation. In the past decade, the channels of obtaining alternative data have grown, as has the raw computing power to crunch and weigh such data. Within the industry, practitioners tell wild stories—of trading equities by using satellites to count cars in parking lots, as a proxy for economic activity; or of planting an infrared camera outside a Tesla plant, to determine how busy it was at night and therefore how full its order book was. Some of this is what one expert calls “innovation theater,” but investors also glean genuine value out several of these strategies.

On a trading desk, “all these kinds of alternative information will be among maybe 30 or 40 different inputs of data, and traders will look at them all to make decisions on what to buy or sell,” said Hari Balaji, the co-founder of Egregore Labs, a Delhi-based firm that builds products to analyze unstructured financial data. At the minimum, said Ben Ashwell, the editor of IR Magazine, which tracks the investor relations sector, “this alternative data may inform a hedge fund manager’s thinking. These managers will meet quite regularly, once a month, with the executives of companies they’ve invested in. So the manager might ask different questions during the next meeting, or dive slightly deeper.”

Machine downloads of firms’ SEC filings quickened in this century: from fewer than half a million downloads daily in 2005, to just under 10 million in 2011, to 165 million in 2016. Not all of these downloaders wanted to wring trading intelligence out of these texts, said Tim Loughran, a professor of finance at the University of Notre Dame; many are programmers searching for meaty data sets and documents on which they can train their algorithms. But banks, hedge funds, and other institutions on the “buy side” also built their own software to grab and parse documents—so much so, Loughran said, that “it’s just robot-land out there now.” The SEC eventually had to restrict the volume of machine downloads during the hours when the markets were open.

Many of these algorithms were trained on a dictionary Loughran helped build in 2011. The Loughran-McDonald Dictionary, updated annually, uses SEC filings and other corporate reporting to determine whether the connotation of a word is positive or negative, or whether it signals uncertainty or potential litigation. At the moment, Loughran said, the dictionary has around 2,300 “negative” words—among them obvious terms like “indict” or “default,” but also less apparent ones such as “petty” and “prone.” Sometimes, Loughran said, former students now working in the quant shops of banks or hedge funds will contact him to say how glad they are for the list. “They spend a lot of time reading reports, and [filings like] 10-Ks are really long. They want to get a quick sense of the sentiment it conveys.” Sentiment analysis software, counting up the positive and negative words in a report, offers just that.

In their upcoming paper, Yang and his co-authors name the 20 institutional investors who were the most active machine downloaders between 2004 and 2016. At the top of the table, perhaps unsurprisingly, is Renaissance Technologies, the hedge fund known for its algorithmic investing, with more than half a million downloads in that 12-year period.

The existence of these sentiment analysis tools is no secret, though. Which means, Balaji said, that companies are now learning how to influence the bots reading their reports. “The stakes are really high here. So the minute they can game the software, they will try to game it.”

These efforts take various shapes. Institutionally, companies are centralizing all corporate communication “to tightly manage the specific words used…since they are being stored to develop a trackable lexicon to feed AI automated trading algorithms,” a report from the National Investor Relations Institute said last year. At T-Mobile, Paellmann said, the public relations team knew that media companies use bots for routine stories to save their reporters time, and that algorithms write many of the reports that summarize earnings releases. “So they’d draft the releases thinking about what information to present first, so that the first headlines coming out on company earnings would sound positive.” For other documents, such as quarterly reports or SEC filings, Paellmann’s team tried to alter as few of the words as possible from quarter to the next. “Some of these bots could look at materials and see where changes have been made, as an indication of where the tone of the company has changed. We were aware of that, so we were very careful in changing the language.”

When changes are made, the most sophisticated companies pay Johnsonian attention to their lexicons. Ashwell, the editor of IR Magazine, recalled being told, by the investor relations executives of a Canadian insurance company, that they used IBM’s Watson to scrutinize their language for sentiment. Words cataloged as “negative” in the Loughran-McDonald dictionary are swapped out for synonyms it doesn’t list. Yang and his co-authors found that, in the pool of corporate filings they studied, the average document used 1.63 negative Loughran-McDonald words per 100 words. But there were four other words per 100 that another taxonomy, the Harvard General Inquirer psychological dictionary, classed as “negative” that Loughran-McDonald doesn’t include. Admittedly, not all of the Harvard words will be necessarily have negative implications in a financial context, Loughran pointed out. “The Harvard dictionary considers ‘liability’ a negative word, but no reader of corporate reports will read one and go: ‘Oh my gosh, they said liabilities!’” Even so, the deliberate bypassing of Loughran-McDonald’s “negative” words is statistically clear: The frequencies of those terms shrank significantly after its publication. The five most-avoided words, ranked by the drop in their usage, were: “restatement,” “declined,” “misstatement,” “closure,” and “late.”

This tug-of-war between companies and their automated analysts is likely to result in a stalemate. Companies still have to make their disclosures, and they still have to do so in language that meets regulatory standards. As Ashwell pointed out: “I don’t think we’ll get to the point where people say: ‘We’re bidding adieu to our dividend payments this quarter.’” And in large, complex companies, the sentiment behind language often gets overshadowed by more pressing and immediate concerns. Since the fund of words that can be permissibly used is limited, the bots will eventually learn them all.

Eventually too, though, these improved bots will be ubiquitous. Everyone will use them—which is, in the quest for an edge, the same as no one using them. Then the game will move on to the next tactic. “What I’m wondering now is whether there’s a tool being developed that reads the body language of executives,” Ashwell said. “Do they have physical tells? Will a company find its CFO is more relaxed if he’s in a home office? Now that we’re all on video all the time, that’s what I’m interested in.”