First things first. There are plenty of reasons to think that the global economy could continue to power forward.

The US economy seems to be emerging from its winter’s nap. China’s economic managers look ready to embark on a mini-stimulus push. German industrial production continues to push forward. Japan’s manufacturers are feeling better than they have in years.

But there are also reasons to worry about what economists politely call “downside risks.” Here are some that everyone should have on their radar screen.

European disinflation

European prices are climbing at their slowest pace since the worst of the financial crisis, when prices actually fell. Deflation is a dangerous place for an economy to be, as declining prices act as a persistent headwind to economic growth. What’s more, there’s no clear cure to deflation once it sets in. (Just ask Japan.)

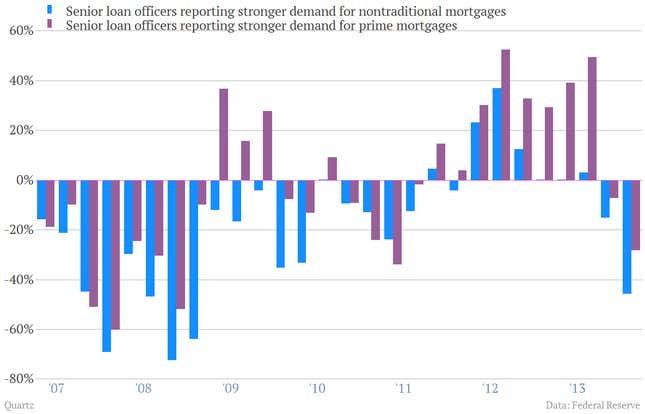

After the “taper”

Lending is the lifeblood of any large, advanced economy. And a recovery in demand for loans—specifically mortgages—has been an important part of the of the US recovery over the last couple years. The Fed’s survey of senior lending officers showed a sharp downturn in demand for mortgages during the first quarter. Let’s hope it was just the weather.

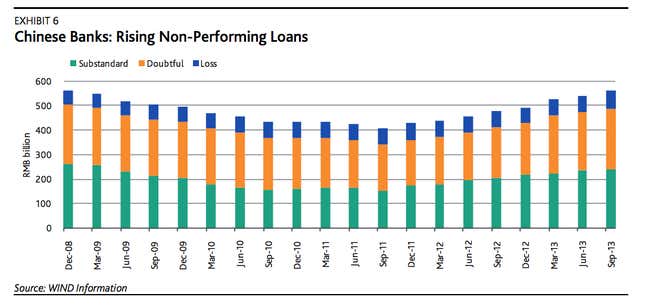

China’s credit conundrum

There’ve been plenty of rumblings that China could be about to experience a Bear Stearns-style “Minsky moment” when investors suddenly perceive risks where they previously only saw profits. Given the fact that the financial system is already largely backed by the government, we can’t see an outright financial crisis as being in the cards. Rather, as the credit cycle turns in China, the risks seem tilted toward a Japanese-style system of unhealthy zombie banks that sap growth. Such a scenario would prompt economic forecasters to rapidly rethink the prospects for global growth.

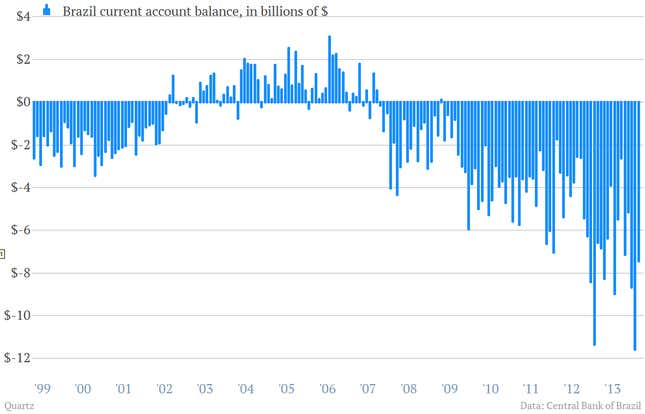

Brazil’s ballooning current-account deficit

China’s slowdown could endanger the growth model of other giant emerging markets. For instance, as commodity prices have fallen, Brazil’s current-account gap has gotten much worse. (Essentially, this is the best measure of how much a country has to borrow from abroad.) So far, investors in Brazil have been more than willing to continue to finance the South American giant. But with ongoing unrest and elections in the offing, it’s not too hard to imagine a destabilizing outflow of capital.

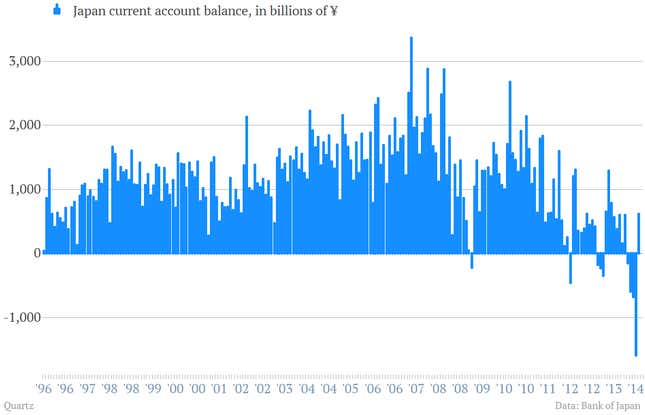

Japan’s shift from creditor to debtor

Speaking of current-account deficits, in recent months Japan notched some of the biggest on record, meaning it was becoming an importer of capital instead of a lender to the world. (Japan’s government has a lot of debt, but the economy as a whole has long run current-account surpluses.) Plainly put, if Japan ran persistent current-account deficits, it would need foreign investors to buy its government bonds. They’d likely demand higher interest rates. Those higher rates would make the debt, already nearing 230% of GDP and predicted to keep growing under Japan’s economic stimulus program, pile up even faster. That could set off the kind of negative debt dynamics that we’ve seen drive once rock-solid creditors—like Italy—to the brink in recent years. And because Japanese government bonds—like US Treasurys—are a bedrock of the global financial system, that would be a terrible thing for global growth.