Researchers have known for decades that commodity agriculture is driving deforestation. But a new study by the non-profit World Resources Institute (WRI) puts a much finer point on how this is dominated by just one product: beef.

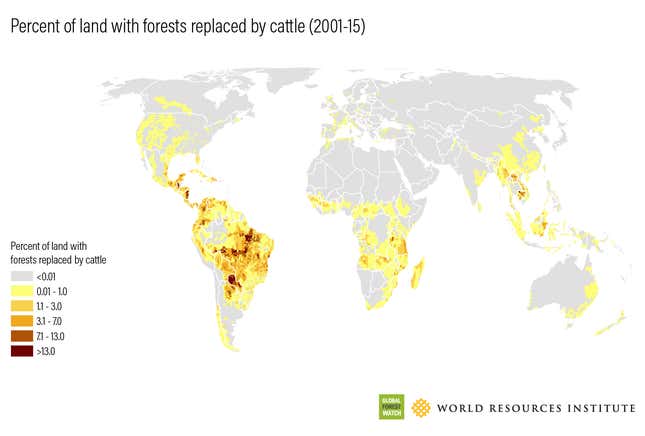

WRI looked at global satellite imagery between 2000 and 2015. It found seven commodities accounted for 72 million hectares of lost forest, an area double the size of Germany. Of that, cattle ranching is responsible for 16% of total tree cover loss, or 45.1 million hectares, an area roughly equal to Sweden. It is followed by palm oil (10.5 million hectares) and soy (7.9 million hectares). Together, these seven commodities accounted for 57% of all deforestation from agriculture.

Much of these losses are concentrated in the tropics. In Asia and Africa, palm oil and chocolate were major drivers of deforestation. In South America, cattle and soy were the primary culprits, particularly in the Brazilian Amazon, one of the greatest remaining natural forests on the planet. Deforestation there is now at a 12-year high after Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro has relaxed environmental enforcement.

But there are some good news for forests: The rate of losses has been declining for palm oil and soy production from highs in the mid- to late-2000s. That is thanks to lower commodity prices, stricter national policies against deforestation, and corporate efforts to clean up supply chains, says WRI.

So far, though, these measures are proving difficult to apply to cattle ranching in Brazil, says Rachael Garrett, an environmental policy professor at ETH Zurich, a research university in Switzerland. Forest cleared for cattle is then held until the land values rise before it is sold to soybean producers. Cattle are easily moved around to obscure their connection to illegal deforestation. Since only a quarter of the country’s beef is exported, the industry has been insulated from international pressure.

“Companies who source beef and leather are well behind other companies in making commitments to eliminate deforestation in their supply chains,” Garrett wrote by email, “and well behind other sectors in actually implementing their commitments effectively.”

But the international mood is shifting. Nearly 500 major food retailers, traders, and processors globally have now adopted supply chain policies to support farmers who grow food without clearing forests. More than half of these initiatives, Garret found in her new research published in Environmental Research Letters, succeeded at slowing deforestation and improving livelihoods.