China’s ban on the BBC is worse than it sounds

China’s National Radio and Television Administration announced on Friday (Feb. 12) that it would pull the BBC World News off air, following critical reports from the British broadcaster and the ban of a Chinese channel in the UK. Observers could be forgiven for shrugging their shoulders; after all, the BBC is not available in most Chinese households.

China’s National Radio and Television Administration announced on Friday (Feb. 12) that it would pull the BBC World News off air, following critical reports from the British broadcaster and the ban of a Chinese channel in the UK. Observers could be forgiven for shrugging their shoulders; after all, the BBC is not available in most Chinese households.

But that announcement was followed by another one, this time from Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK), the city’s main publicly funded broadcaster. RTHK used to carry BBC World Service radio every night from 11pm to 7am local time; from Friday, it no longer does. It also stopped relaying a once-weekly BBC radio program in Cantonese. (Hong Kongers can still listen to the BBC online and watch it through private cable TV providers.)

That decision has experts concerned that media freedom is eroding further in the global financial hub. It’s “a further indication if we needed one,” says Kevin Latham, a researcher on Chinese media at SOAS University of London, “of the growing influence of the Beijing government in the affairs of Hong Kong.”

Why did China ban the BBC?

The BBC recently published a major investigation into alleged human rights violations against Uyghur Muslims in the Chinese region of Xinjiang. In their statement, Chinese authorities said the BBC’s reporting was not “truthful and fair,” “harmed China’s national interests,” and “undermined China’s national unity.”

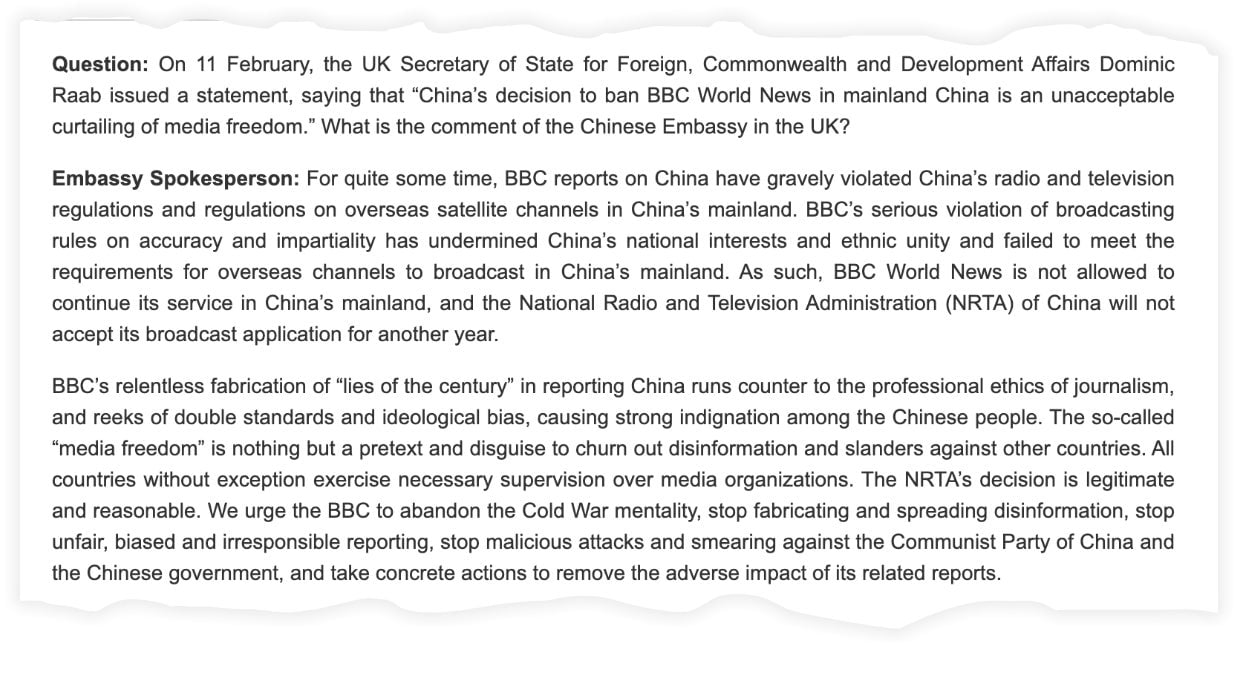

The Chinese embassy in the UK had this to say:

But there may be another, more immediate reason for the ban; a week earlier, British broadcasting regulator Ofcom revoked a license allowing China Global Television Network (CGTN) to operate in the UK because its owner violated rules on editorial oversight. This was a big blow for CGTN, which planned to make London the base for its European operations. Because the license was non-transferrable, CGTN also lost its ability to broadcast across Europe.

Many saw the BBC ban as retaliation. In response, the BBC said it was “the world’s most trusted international news broadcaster and reports on stories from around the world fairly, impartially, and without fear or favor.” The UK said “China’s decision to ban BBC World News in mainland China is an unacceptable curtailing of media freedom.”

“One country, two systems” and media freedom in Hong Kong

Hong Kong is a former British colony and has greater access to the BBC because it benefits from “one country, two systems,” the architecture that Britain helped put in place to preserve Hong Kong’s economic and personal freedoms after its return to China in 1997.

Under this system, Hong Kongers were promised democratic rights, including a free press, for 50 years; and while the same right is technically enshrined in China’s Constitution, in practice, media in the mainland is not free and the Great Firewall prevents access to many foreign outlets. This means that even before the ban, the BBC was only available in about a million hotel rooms.

RTHK’s BBC ban shows that the independence afforded to Hong Kong media under “one country, two systems” is disintegrating, and that the “gap in terms of access to information and media freedom between Hong Kong and the mainland is shrinking,” says Sarah Cook, research director for China and Hong Kong at the US nonprofit Freedom House. It has experts worried that access to other news outlets could be blocked in Hong Kong in the future if they publish reports critical of China.

RTHK has been under particular pressure from authorities in Beijing, who view the broadcaster’s coverage of popular protests—from the 2014 Umbrella Movement to this past year’s protests over the imposition of a security law—as harmful to their interests. As early as 2007, Freedom House noted in its yearly report (pdf, p. 157) that “a government review of…RTHK prompted fears that [it] could be turned into a government propaganda channel.”

The BBC is the latest low point in worsening relations between London and Beijing, with companies on both sides—from HSBC to Huawei and CGTN—caught in the middle. According to Latham, the BBC ban “could be the thin end of the wedge,” or it “may just be the next step in the tit-for-tat battle between the UK and China.”