The US government has spent lavishly to boost the economy during the pandemic, and Americans like it—like it so much, in fact, that history suggests that high levels of public expenditure will continue to be a norm for a long time to come.

“People come to benefit from it and then to expect it,” said Price V. Fishback, a professor of economics at the University of Arizona. “That makes it harder to go back to a time of low spending.”

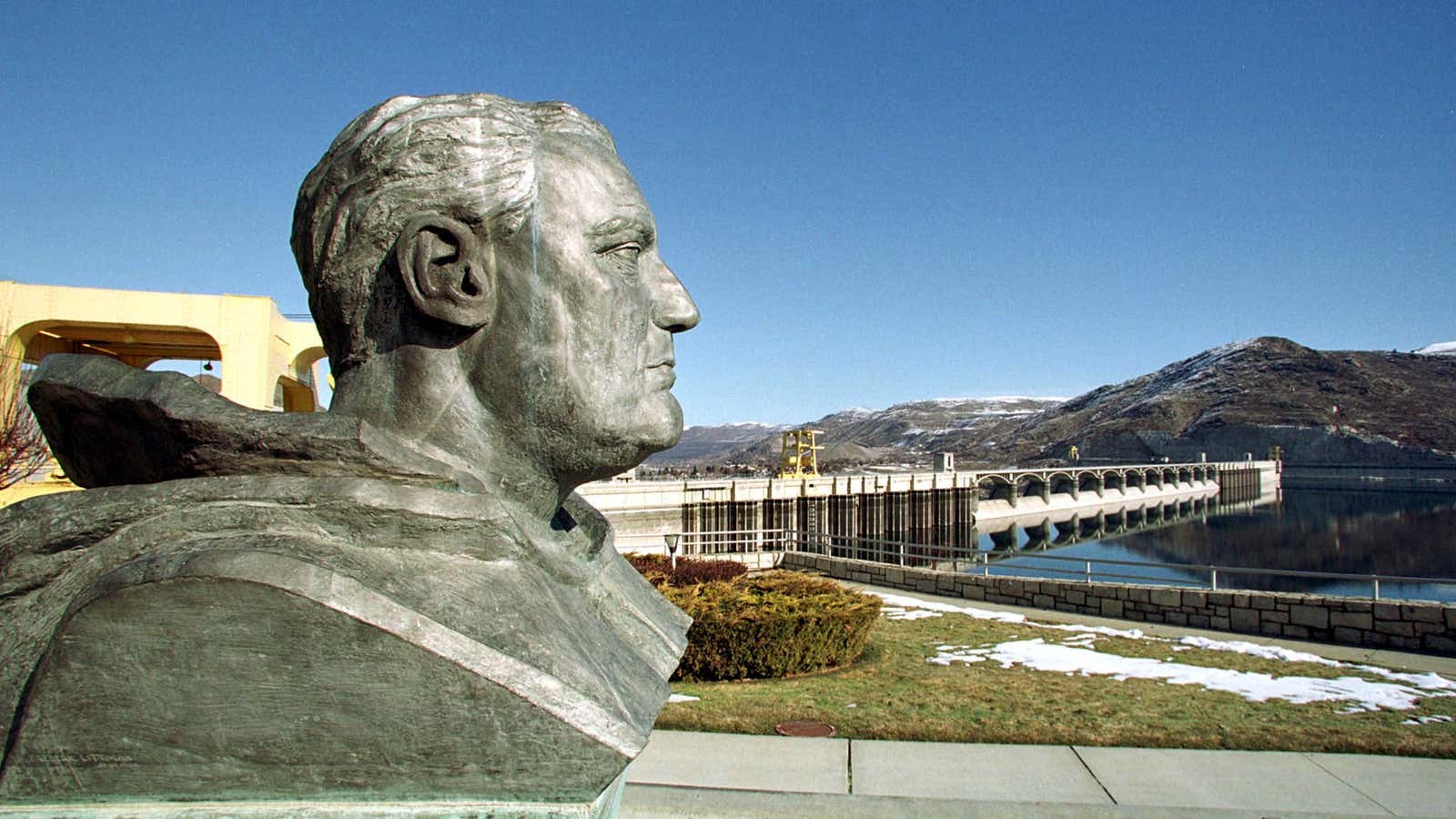

Fishback knows it has happened before. His principal area of research is the political economy of the New Deal, a period of intense public expenditure during the Great Depression that gave way to the even greater spending of World War II. “Federal net outlay, as a share of GDP, went from 3% to 9% by the end of 1933, and then to nearly 10% by the end of the 1930s,” Fishback said. “The war comes in, everything explodes, and it’s 41% by 1944.” It wasn’t just that the government spent on infrastructure or welfare or the military, he said. It was that the government imposed more regulation and taxes as well. The state grew bigger in nearly every way.

And it never permanently came back down. Just after 1945, the government stopped spending on fighting the war, so a sharp dip ensued, but then spending began to climb again. By the time Ronald Reagan became president, net outlay was still at around 20% of GDP. “Reagan just slowed the growth of big government. And in the terms of Reagan and the first Bush administration, they were running deficits of around 4-5% a year.” The largest peacetime spike—until the pandemic—came just after the 2008 recession, when federal net outlay touched 24%.

As of now, after Covid-19, the figure has hit 36%, assuming all allocated money has been spent, Fishback said. And president Joe Biden’s proposed $1.9 trillion stimulus has not yet been factored in. “That’s a pretty substantial number, 1.9 trillion,” he said. “The GDP in 2019 was $21 trillion, so it’s close to 10% of GDP on its own.”

What did governments spend on?

There were plenty of things that needed government money after the war, Fishback said: defense and nuclear energy, during the Cold War; Medicare and Medicaid; social security; the GI bill. But also, he said, “people were just willing to expect more government.”

Indeed, the American government grew on the back of emergencies such as the Great Depression and the world wars, the economist Robert Higgs found in his book Crisis In Leviathan (Higgs has described himself as a “libertarian anarchist,” and his book has an elegiac nostalgia for “a time, long ago, when the average American could go about his daily business hardly aware of the government—especially the federal government.”) Analyzing the effect of the wars and the Great Depression, Higgs wrote: “Chief among the enduring legacies of emergency governmental programs has been ideological change, in particular a profound transformation of the typical American’s beliefs about the appropriate role of the federal government in economic affairs.”

It isn’t just the public that comes to prize such expenditure, Fishback said. The political opposition to it reduces too. Republican governments through the second half of the 20th century didn’t always aim to be leaner. In no presidency, Republican or Democrat, since that of Dwight D. Eisenhower has the US seen a decline in federal spending as a proportion of GDP—and Eisenhower himself, in the midst of expanding Social Security, building highways, and constructing low-income housing, only brought spending down from 20.4% to 18.4%.

The pandemic represents another crisis of the kind Higgs discussed in his book, so if his observation is any guide, the size of the state and its expenditure will not shrink in a hurry. “It’s easy to for people to think: ‘Yeah, I survived the pandemic only because of this money,'” Fishback said. “It will open the door for more spending.”