In China, family really is everything. Alvin Jiang, the 28-year-old grandson of former president Jiang Zemin and head of one of the country’s hottest private equity firms, stands to make millions from two of China’s largest initial public offerings—those of e-commerce giant Alibaba and state debt trader China Cinda Asset Management, according to a report (pdf) by Reuters.

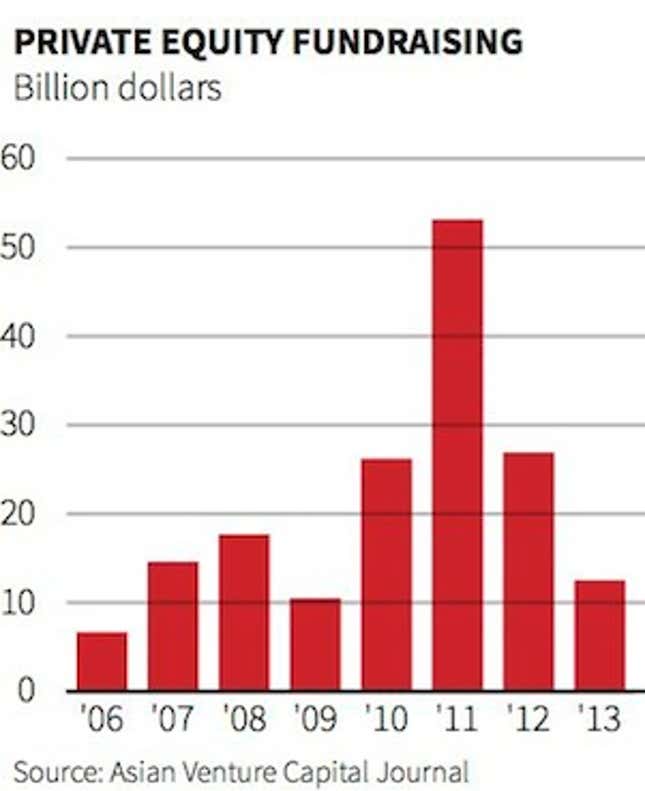

Jiang is one of a growing number of sons and daughters of former and current Chinese officials dominating China’s still nascent private equity industry. Traditionally, the offspring of China’s elite political families, often known as “princelings,” have gravitated toward real estate, state-owned enterprises, or government positions. But over the past several years, many have moved into high finance (paywall), where returns are potentially much higher. According to Reuters, the country is home to at least 15 investment firms founded or led by princelings. These operations have raised at least $17.5 billion since 1999, according the newswire.

Most famous among them right now is the young Jiang. A Harvard graduate whose previous experience consists of working as an analyst for Goldman Sachs’ private equity unit, Jiang started Boyu Capital in Hong Kong at the tender age of 25. He has raised $1.6 billion and is finalizing another $1.5 billion funding round. Boyu also stands to make a hefty profit from its 2011 stake in Sunrise Duty Free, which operates duty free stores in the Shanghai and Beijing airports, a deal that showed Jiang’s ability to gain access to strictly state-controlled sectors.

Other notable princelings of private equity include: Winston Wen, the son of former premier Wen Jiabao: Liu Lefei, the son of Politburo member Liu Yunshan; and Jiang’s own father—Jiang Mianheng, the son of Jiang Zemin—who was a pioneer of private equity and is now CEO of Shanghai Alliance Investment Limited, a state investment company that operates similarly to a private equity firm.

There’s no proof that the former Chinese president helped the younger Jiang’s ventures. But critics of princeling-dominated private equity say nepotism—or even the appearance of nepotism—can damage China’s entire financial system.

The Chinese public has long seen politics and business as closely intertwined. By helping to channel money to growing and promising companies, some believe private equity has the potential to modernize China’s financial system. But a bias toward firms with political links may be pushing out foreign operations, as well domestic ones with less connections. Princeling-run private equity has been criticized for unprofessionalism and poor investments. Moreover, China’s conflict-of-interest laws are weak, and the opaque nature of private equity deals makes the business even harder to scrutinize.

As progeny of China’s Red Nobility proliferate, however, the princeling advantage in private equity and other realms of business may fade. Victor Shih, a China expert at Northwestern University, observed in 2012: ”You’ve got the children of current officials, the children of previous officials, the children of local officials, central officials, military officers, police officials. We’re talking about hundreds of thousands of people out there — all trying to use their connections to make money.”