Nearly 20 years ago, a friend of mine left a farm in West Africa and came to America alone. He worked his way through college by doing manual labor and acquired a few ivy-league degrees. Today he works at a hedge fund and is a member of the illustrious 1%.

He’s also afflicted with the concerns of the first-world elite: He worries about his ability to afford the “right” private schools for his future children, how competitive it will be for them to get into a good college and land a prestigious job. I often point out he did well with much less—his elementary school didn’t even have walls and the only qualification necessary to teach at his primary school was having gone to primary school.

With his DNA and work ethic, his children will do just fine, even if they don’t attend a top tier Manhattan pre-school. But he always shakes his head and tells me it’s “different when you are an immigrant—it’s much harder if you’re born here to move up the ladder.” In some ways he’s right. Immigrants tend to be exceptional people. They are more likely to start a business, file patents, and have a job than native-born Americans.

This group exhibits selection bias—anyone motivated enough to move to a new country and endure the arcane immigration process is exceptionally ambitious and smart. Many come with very little, manage to advance, and (contrary to my friend’s conjecture) their children often do even better—carrying on their family’s economic advancement. Immigrants complicate the notion that we live in a society where natives can’t change the economic class they were born into. So does that mean the key to economic mobility comes down to pluck and not institutional, economic forces like education, racism, and inequality?

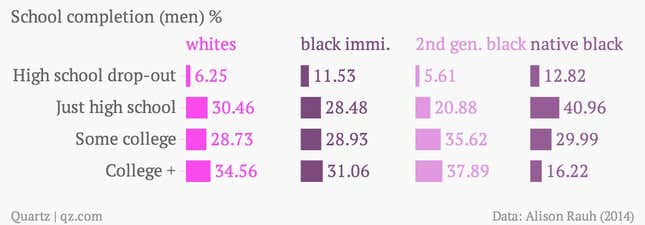

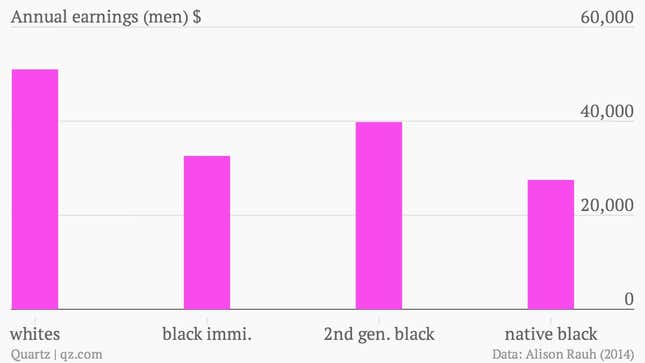

A new paper (pdf) from University of Chicago PhD candidate Alison Rauh finds that black immigrants tend to be more successful than black Americans. They out-earn black natives (after accounting for age) and are more likely to be employed. This is not surprising; white immigrant groups outperform their native cohort too. But what’s most intriguing is how their children fare. The children of black immigrants are more likely to go to and complete college than native blacks (and whites) and are less likely to drop out of high school.

The children of black immigrants also earn more than native blacks or first generation immigrants.

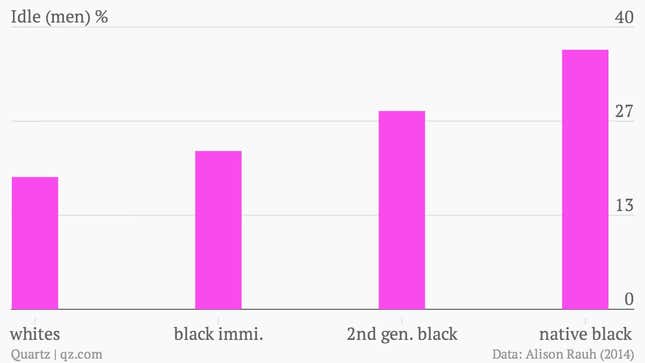

But, the fact that children of black immigrants earn more than their parents comes with an important caveat. Like all ethnic groups, the children of black immigrants only out-earn first generation immigrants if they work, but many children of black immigrants don’t work. Their rate of idleness (not being in labor force or in school) is much higher than the idleness rates of whites or black immigrants. It is near the very high rate of idleness for native-born black Americans, in spite of their having more education. At nearly every education level, black immigrant children have a higher rate of idleness than whites or first generation black immigrants.

Children of black immigrants are an interesting group. It seems their economic outcomes go one of two ways: They either out-perform their parents, continuing a rise through the economic ranks or they flounder and face the same economic challenges of native-born black Americans. The disparate performance of black immigrants’ children is unique. There is a distribution of outcomes, but on average, children of Asian immigrants out-earn everyone—including native-born whites (their idleness rates also converge to Asian natives but this rate is so low to begin with it’s unremarkable). Second generation Hispanic immigrants are nearly identical, in economic outcomes, to native-born Hispanics.

So why the disparity with blacks? Rauh observed that children of educated, black immigrants (ones who went to college) typically have higher rates of employment and earnings (my friend can rest easy). But parent education doesn’t explain everything. Rauh believes both discrimination and assimilation (subscribing to a culture of not working) also play a role in economic attainment. She measured their impact by looking at where the immigrant families lived and found that children of black immigrants who grow up in a more segregated area (which captures assimilation) or areas that have higher rates of discrimination are less likely to work.

In Slate, Jamelle Bouie recently wrote about how black Americans tend to live in poor, segregated neighborhoods, even if they are middle class because people tend to stay in the neighborhoods they grow up in. He claims this is an impediment to climbing the economic ladder because these communities lack good schools, professional networks, and more exposure violence. Rauh’s research suggests living in a poor, segregated community is not the problem, but rather growing up in one. She found that black immigrants are more likely to work and earn more than native blacks no matter where they live. But community has a bigger impact on their children. Growing up in an environment where blacks are discriminated against might quash the ambition and expectations of children of black immigrants. But a segregated or racist community may not have the same impact on immigrants because they come to American with their identity, education, and ambitions more fully formed. Rauh found the older people are when they immigrate the more likely they are to work and immigrant children who are raised in integrated communities are more successful. They may be less affected by racism and prone to assimilation of black natives, or it could be community choice might reflects the values and preferences of their parents.

The lack of economic mobility in America, compared to other rich countries, is difficult to reconcile with the fact that America remains the land of opportunity for many immigrants. The experience of black immigrants provides an interesting case study as to what factors hold Americans back from advancing. There exists no one-size-fits all solutions—different groups in America face their own variety of challenges. But what keeps the children of black immigrants out of the work force is the same thing that ails many native-born Americans. Improving economic mobility will take more than examining our economic institutions and worrying about inequality. Culture, expectations, and how they interact with these institutions matter too.