The UK is “a model for other white-majority countries.” That’s according to the UK’s Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities, which published its delayed report on March 31, concluding additionally—to immediate anger and derision—that the UK experiences no institutional racism. The commission found anecdotal evidence of racist acts, its chair Tony Sewell told the BBC. “However, evidence of actual institutional racism? No, that wasn’t there, we didn’t find that.”

That isn’t entirely surprising, Stokely Carmichael, the American civil rights organizer, would have responded.

The term “institutional racism” was Carmichael’s coinage. It appeared first in “Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America,” a book Carmichael wrote with Charles Hamilton in 1967. A reader runs into the phrase right away, in the second paragraph of the very first chapter. The writers distinguish individual acts of racism—which can “be recorded by television cameras” or otherwise “observed in the process of commission”—from institutional racism: “less overt, far more subtle, less identifiable in terms of specific individuals committing the acts.” (The italics were Carmichael’s and Hamilton’s.)

But institutional racism exists, “it permeates the society,” Carmichael and Hamilton wrote. And its effects were certainly palpable—in the higher death rates of Black babies, for instance, or in how Black families couldn’t break free of their tenements. Like gravity, institutional racism couldn’t be seen, but it could be felt by the minorities who became its victims.

The history of the term “institutional racism”

Carmichael’s diagnosis of the problem didn’t go down easily. In the circles of power in majority-white countries, the concept of institutional racism was frequently contested and rejected. Some of this was willful, the rejection itself an act of racism; some of it was an inability to see systemic processes at play; some of it was a blind belief in the ostensibly meritocratic practices of these societies. And some of it was a compulsive need to re-define and re-anatomize what Carmichael and Hamilton had already defined and anatomized so well.

Here is the history of these contestations, as told through the stories of four government inquiries—the last being the one Sewell chaired for 10 Downing Street.

The year after “Black Power” was published, the Kerner Commission published its report about riots in African American neighborhoods through the 1960s. The report blamed racism for creating the conditions that led to the unrest: “White society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.” These conclusions received wide publicity, but in polls, 53% of white Americans rejected them.

The term “institutional racism” was perhaps too new to use, but the commission did urge the government to adopt policies that addressed “institutional sources of racial disparity.” US president Lyndon Johnson’s government ignored this suggestion, the historian Alice George wrote, and “white response to the Kerner Commission helped to lay the foundation for the law-and-order campaign that elected Richard Nixon to the presidency later that year.” In other words, the problems of institutional racism were met with more institutional racism.

Institutional racism in the UK

The British institution that has most frequently been charged with institutional racism is the police. In 1981, Lord Scarman, a judge, led an inquiry into riots in the London locality of Brixton. Scarman’s report is remarkable for how it identified, again and again, the symptoms of institutional racism even while denying that institutional racism existed.

Minority representation in the police force was poor, Scarman admitted. Black people were stopped and searched far more frequently than others. The police failed to build bridges with minority communities and to earn their trust. “Racial prejudice does manifest itself occasionally in the behavior of a few officers on the streets,” Scarman wrote. But he rubbished the idea that the police or indeed British society “knowingly, as a matter of policy, discriminates against Black people”—unable or unwilling to perceive that systemic racism could operate outside of explicitly racist policy.

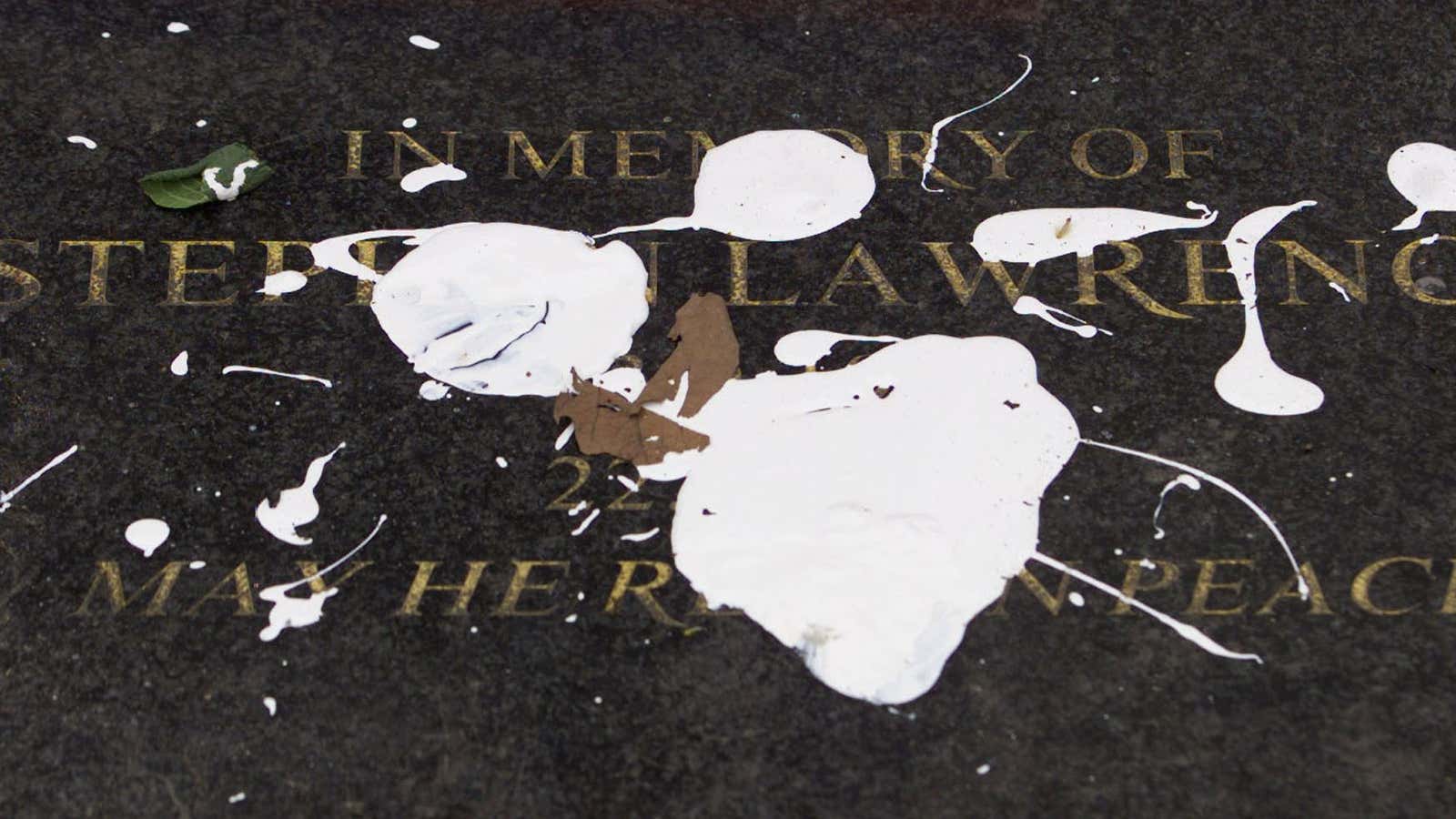

Another year, another inquiry into the British police. In 1999, Sir William Macpherson submitted his report on the police’s investigation of the murder of Stephen Lawrence, a Black teenager. Macpherson insisted he didn’t want to produce “a definition cast in stone” of institutional racism. But, quoting Carmichael and Hamilton, he recognized that the phrase couldn’t just be limited to “explicit manifestations of racism at direction and policy level.” Institutional racism was present in the aggregate—in the sum of the words and actions of individual officers, and through the effects of these words and actions.

Institutional racism in the UK in 2021

Given this history, the report produced by Sewell’s commission takes a big step backwards. Unlike Macpherson’s report, this one obsesses about defining institutional racism. And it does so by looking for explicit “discriminatory processes, policies, attitudes, or behaviors”—an approach that was outdated and futile even when Macpherson rejected it.

Ironically, the consequences of institutional or systemic racism aren’t very hard to find—either in a Covid-hit society or in Sewell’s own report. Multiple studies have found that ethnic minorities are disproportionately at risk during the pandemic, because of the nature of their jobs, their housing situations, or their ability to access healthcare. Sewell’s report points out that several minority groups have less substantial savings to fall back on, and that employment rates among minorities fall far more than the overall employment rate during economic downturns in the UK.

The report cites other examples. Minorities find it harder to get financing to start their own businesses. Only 52 of the 1,099 “most powerful jobs” in the UK are held by people from minority groups. None of the FTSE 100 firms has a Black CEO, CFO, or chair, as of February. If a violent crime is committed, it’s likely that the victim is from a minority group, and “for every White victim of homicide aged 16 to 24 in 2018/19, there were 24 Black victims.” These too are the effects of systemic and institutional racism, even if Sewell’s commission refuses to see them as such.