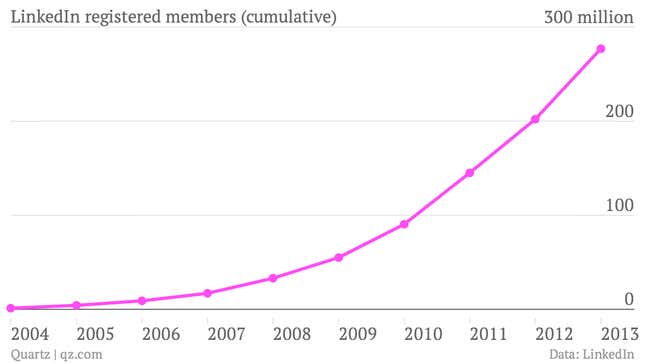

On May 5th, LinkedIn will celebrate its 11th birthday. It announced last month that 300 million people had signed up for the professional social network. This evening, LinkedIn will report earnings for first quarter of this year, which analysts expect to surpass the company’s own guidance.

Despite all these positive signs, there is one question that has dogged the network for the majority of its history: What is LinkedIn actually for?

Establishing a clearer identity is crucial to LinkedIn’s future. While more than 300 million people have joined, LinkedIn’s most recent filings suggest that the number of people who log in at least once a month is probably closer to 200 million. Growth in US monthly desktop users and desktop pageviews both slipped into negative territory last year (though visitors from mobile are climbing). To many, LinkedIn is only a place to go when looking for a job. And despite LinkedIn’s exhortations to users to fill in their profiles to “100% completeness” and “endorse” each other, connections and endorsements on the network are essentially meaningless. LinkedIn needs a way to get users to come back more regularly. That’s why, over the past three years, it has morphed into a content platform.

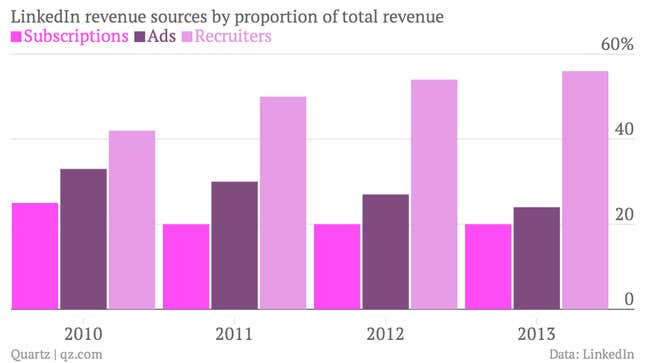

“They would like guys like you and me to look at our LinkedIn newsfeed as part of our morning ritual, the same way some people look at Twitter” says Tom White, an analyst at Macquarie, an investment bank. Getting people to sign up is fine for one part of the business—selling database access to recruiters. But LinkedIn can’t capture ad dollars without a more captive, active audience. ”Ads are probably the largest addressable market, a very high-margin revenue stream,” adds White.

“Content consumption is a daily use-case so we find more of our members visiting LinkedIn on a regular basis,” says Deep Nishar, who heads up LinkedIn’s product and user experience divisions. “When they are more engaged they are engaging not just with content on the site—they are engaging with all sorts of other things that we provide, including, but not limited to, recruiters trying to reach them and marketeers trying to pitch the right messages of their products.”

Sharing from the top down

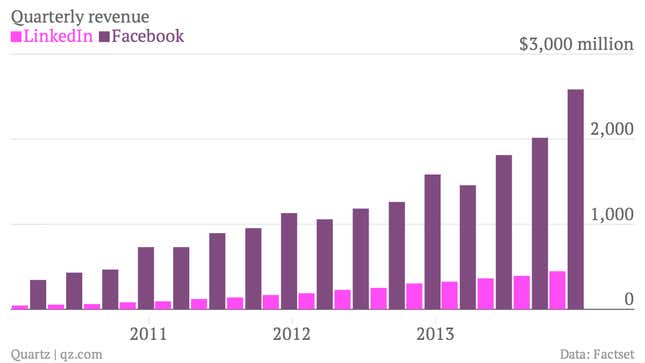

Although LinkedIn is often mentioned in the same breath as Facebook, the comparison isn’t perfect. LinkedIn’s revenue for 2013 stood at $1.5 billion to Facebook’s $7.8 billion. Facebook has well over one billion monthly active users, to LinkedIn’s 200 million. And while Facebook derives the vast majority of its revenue from advertising, LinkedIn’s business still depends largely on payment from recruiters.

Indeed, LinkedIn doesn’t even use the same language as Facebook to describe itself. “We’re not a social network,” a LinkedIn spokesperson said. “LinkedIn is a professional network.” Yet like Facebook or Twitter, LinkedIn would like it if its users posted articles and links—professional in nature, of course—on their timelines.

To get things started, the company launched LinkedIn Today in 2011 as a way of enticing professionals to log in every morning to catch up on industry news. The following year it signed up “influential thought leaders” to provide occasional commentary. Last year, the company bought Pulse, an app that focuses purely on content, and which the company would like professionals to check for a quick update on news relevant to them. And now, it runs a content behemoth that drives the internet’s manicured hordes to business publications around the web.

All these moves are coming now coming together. In February, LinkedIn opened up its publishing platform from a small group of well-known businesspeople, such as Richard Branson, to all its members. It’s a classic online publishing strategy: build-up a readership by linking out to good content and once people are used to finding interesting things on your website, use that traffic to drive your own stuff.

LinkedIn is counting on people to use the network as a platform to express their own thoughts, hoping they will spread the word themselves. Like any writer, those publishing on LinkedIn will want their work to be read, essentially giving LinkedIn free promotion and giving its millions of members an incentive to bring others to the platform. If the approach works, it will boost pageviews and users and, eventually, ad revenue.

Filling the space between the ads

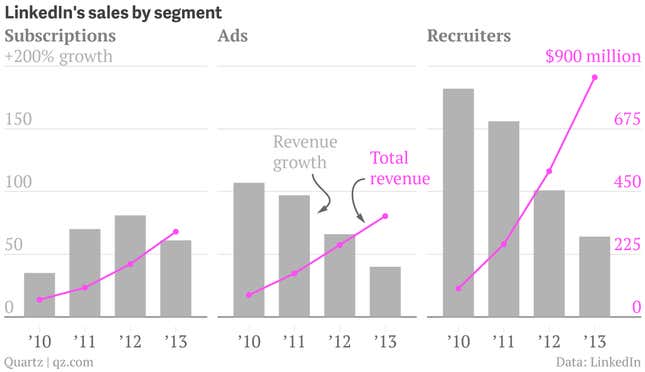

It will soon become clear whether LinkedIn’s content strategy is working. Unlike the giants of the web, LinkedIn does not rely on advertising as its single, or even largest, source of revenue. It does sell ads, but also sells database access to recruiters, who each pay thousands of dollars every month per subscription. It also sells premium memberships to individual users. All three revenue sources are growing at a rapid clip, though the ad business has been growing slowest of all.

If its content strategy works, it would represent tremendous potential for LinkedIn’s advertising revenue. LinkedIn launched a sponsored updates service a little under a year ago. Nishar says the results have been encouraging. He cites the example of Blackrock, a financial firm best known for institutional investment management services. “Turns out they also have a thriving business in investment management for individuals,” he says, a topic around which BlackRock sponsored some content on LinkedIn. Citi is another satisfied customer, according to the company. Sahil Jain, CEO of AdStage, a LinkedIn partner in sponsored updates, says LinkedIn’s segmentation allows for some impressive ad targeting by professional status, which could be more valuable to bigger advertisers.

The market isn’t yet convinced—though analysts are optimistic. Morgan Stanley sees “possible signs of inflection” in LinkedIn’s ad business. “Sponsored Updates is progressing solidly,” writes another analyst, “but not necessarily ahead of expectations.”

The next three billion

LinkedIn is taking a three-pronged approach to convincing the markets. According to Nishar, the company is putting its energies into mobile, international expansion, and “delivering massively personalized experiences.” None of these is particularly surprising: mobile devices are increasingly where users come from, international expansion is the natural place to find new ones, and ”personalized experiences” are the foundation of the modern, data-rich internet. Like any other online business, LinkedIn needs two things in order to grow its revenue: more users and more data from existing users.

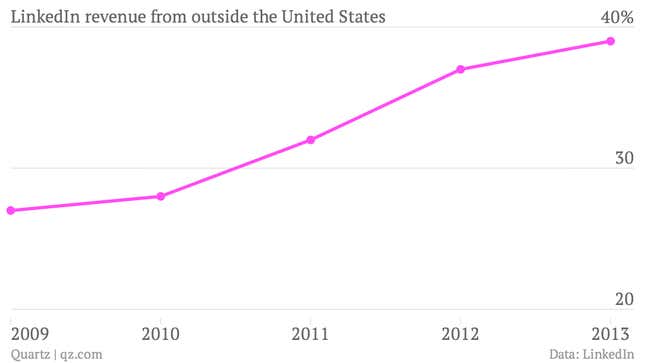

Nishar says LinkedIn is targeting its “the next three billion” users (a counterpart to Mozilla’s ”next two billion” and Facebook’s “next five billion.”) On this point, international expansion is, of course, critical. Non-US users now make up two-thirds of LinkedIn’s membership, versus only one-third five years ago. The company recently entered China. Nearly one-tenth of its members come from India, making it the second-largest country on LinkedIn. Revenue growth in the Asia-Pacific region has outpaced other markets over the past four years. One-third of LinkedIn’s revenue comes from outside the US, and is growing faster than its home market.

Another way to grow membership is by appealing to groups that would not traditionally have sought a presence on the network. Nishar says there are some 700 million white-collar workers in the world. But the global workforce includes ”all sorts of people who work for a living—personal trainers, landscape contractors, plumbers or electricians.” There are 3.3 billion workers in these industries, and LinkedIn wants them all on its network. “What they find is that their work is also dependent on professional reputation [and] word-of-mouth business,” says Nishar. “What better way to get there than LinkedIn?”

In this way, LinkedIn is no different from Facebook, which is constantly exhorting users to engage more with the platform. “I think of it as basically a data play,” says Macquarie’s White:

What LinkedIn is really doing is they’re monetizing all the data that is in yours, mine and the other 300 million people’s profiles. They’re monetizing with recruiters through talent solutions, with advertisers in the marketing solutions business. And they’re soon going to be monetizing with sales professionals.