The US isn’t keeping up with the proliferation of new spacecraft in low-earth orbit, and the potential consequences are serious.

Megaconstellations, like those developed by SpaceX and OneWeb, will add tens of thousands of new satellites to the environment around the planet. University of Southampton professor Hugh Lewis used data from the Center for Space Standards & Innovation to visualize how often satellites are expected to pass by each other, based on their present positions.

Satellite operators become concerned when their satellites are expected to pass within a kilometer of another spacecraft, given the uncertainty involved in predicting their movement. The data show a significant escalation in close conjunctions involving satellites in the new megaconstellations.

In 2019, for example, SpaceX’s Starlink satellites were involved in about 1% of all satellite conjunctions within 1 kilometer; today, the constellation is involved in about 10% of those close passes—after you exclude close passes among Starlink spacecraft.

The findings make sense, since Starlink is the world’s largest satellite constellation, but with more spacecraft coming from countries and companies around the world, expect more conjunctions. Jim Cooper, an engineer at COMSPOC, the space situational awareness company that helped produce this data, says 1 km conjunctions have doubled since 2017, from 2,000 in a month to 4,000.

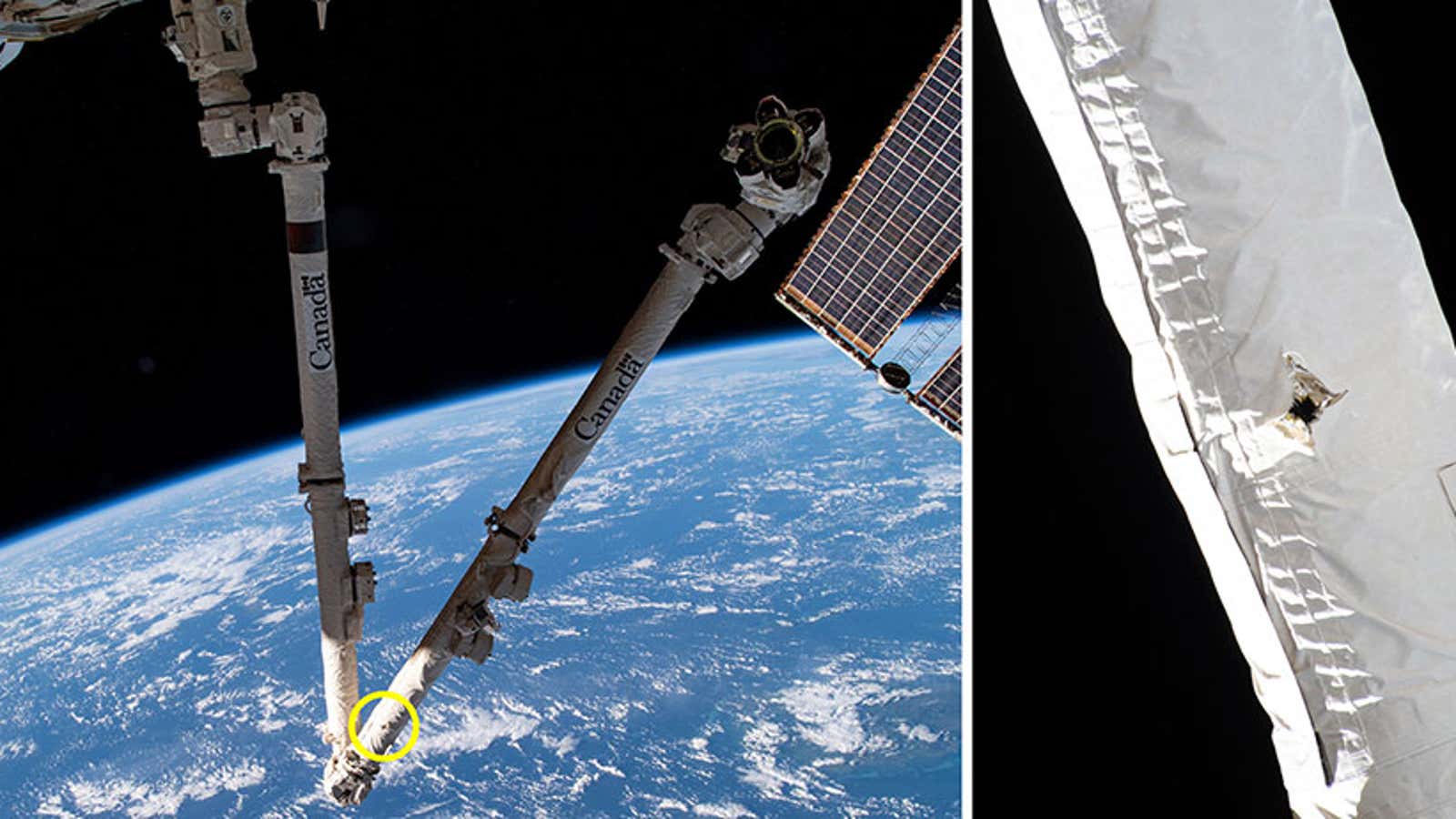

More conjunctions mean more space debris, which can damage anything in orbit. There are business costs, too: Any time a satellite is maneuvering to avoid a conjunction, it is burning precious propellant and time better spent earning revenue.

We don’t need to overstate the dangers here: The likeliest conjunction when this story was published, between two small satellites operated by Swarm, was forecast at a probability of one-tenth of one percent. At the same time, growth of spacecraft in orbit means increased low probability events. As Bill Ailor, who studies spacecraft re-entry at the Aerospace Corporation, puts it, once you start adding up lots of low probability events, “you start getting some numbers you might want to think about.”

And people have thought about space traffic management, and new standards to keep up with the revolution in satellite use. The Trump administration ordered the US government to develop a proper approach to the problem in 2018. In 2020, a special National Academy panel concluded that the Department of Commerce’s Office of Space Commerce was the right agency to handle the job and encouraged Congress to pay for the project.

And since then? Not much. President Joe Biden has yet to nominate anyone to run the Office of Space Commerce, and experts fear a lack of White House support could lead to brain drain and missed opportunities. Congress has yet to appropriate funds for the agency to set up a clearinghouse for orbital tracking data or write rules for American spacecraft there. The Endless Frontier Act, a bill filled with a slew of investments in research and technology, may wind up funding this project. Meanwhile, the European Space Agency has already set up its own operations center to pilot a space traffic management system.

“The challenge is being posed to the US in terms of leadership, because we’ve lost some of our momentum,” Cooper says. He’d like to see the US start a pilot project using private companies like his to create a useful system for public and private satellite operators alike, which currently rely on the Department of Defense and trade organizations to track their satellites and cooperatively avoid collisions.

The US has been at the vanguard of private investment in space. It should be at the vanguard of making that investment sustainable, too.

A version of this story first appeared in Quartz’s Space Business newsletter.