Tokyo came with its game face ready. Soon after the city was confirmed as host of the 2020 Olympic and Paralympic games in 2013, officials began planning for how to move millions of visitors around on Tokyo’s roads and infamously complex train system.

At one point, Tokyo was preparing for 10 million (link in Japanese) athletes, coaches, and spectators to descend upon the city. Then, of course, a global pandemic laid waste to all those plans. Japan has gone from limiting the number of foreign spectators that could attend the games to banning them entirely, and has declared a state of emergency for Tokyo that will last at least through the duration of the Olympics. For visiting athletes and others, transportation plans are now centered around safety and preventing contagion.

The original plans to increase transit capacity

The last time Tokyo hosted the Olympics in 1964, the city used the events as an opportunity to debut the Shinkansen bullet train that’s become the world standard for high speed rail. For this Olympics, the city went to great lengths to ensure that its train system—which is already-stretched thin—could withstand the extra demand of 800,000 additional users every day of the games.

Efforts included adding extended train service in the greater Tokyo area for at least 70 lines across 19 municipal and private train companies. A new railway station built in a central district of Tokyo opened on March 14, 2020, three days after the WHO declared Covid-19 to be a global pandemic, and 10 days before the Olympics were postponed.

Companies were set to encourage employees take vacation and work from home during this period. Olympics officials suggested employers “introduce” teleworking at their companies to further reduce demand on transit.

Shifting focus to pandemic safety

The need to meet a surge of transit demand disappeared once spectators were banned from the events. Earlier, when it looked like fans would be allowed at events in limited numbers, plans were put in place to make sure that trains and buses were properly disinfected and ventilated, but now even these measures have been rendered unnecessary, much to the disappointment of staff who made the preparations, says Katsuhiro Nishinari, a Tokyo University professor who has worked with the organizing committee on transportation management.

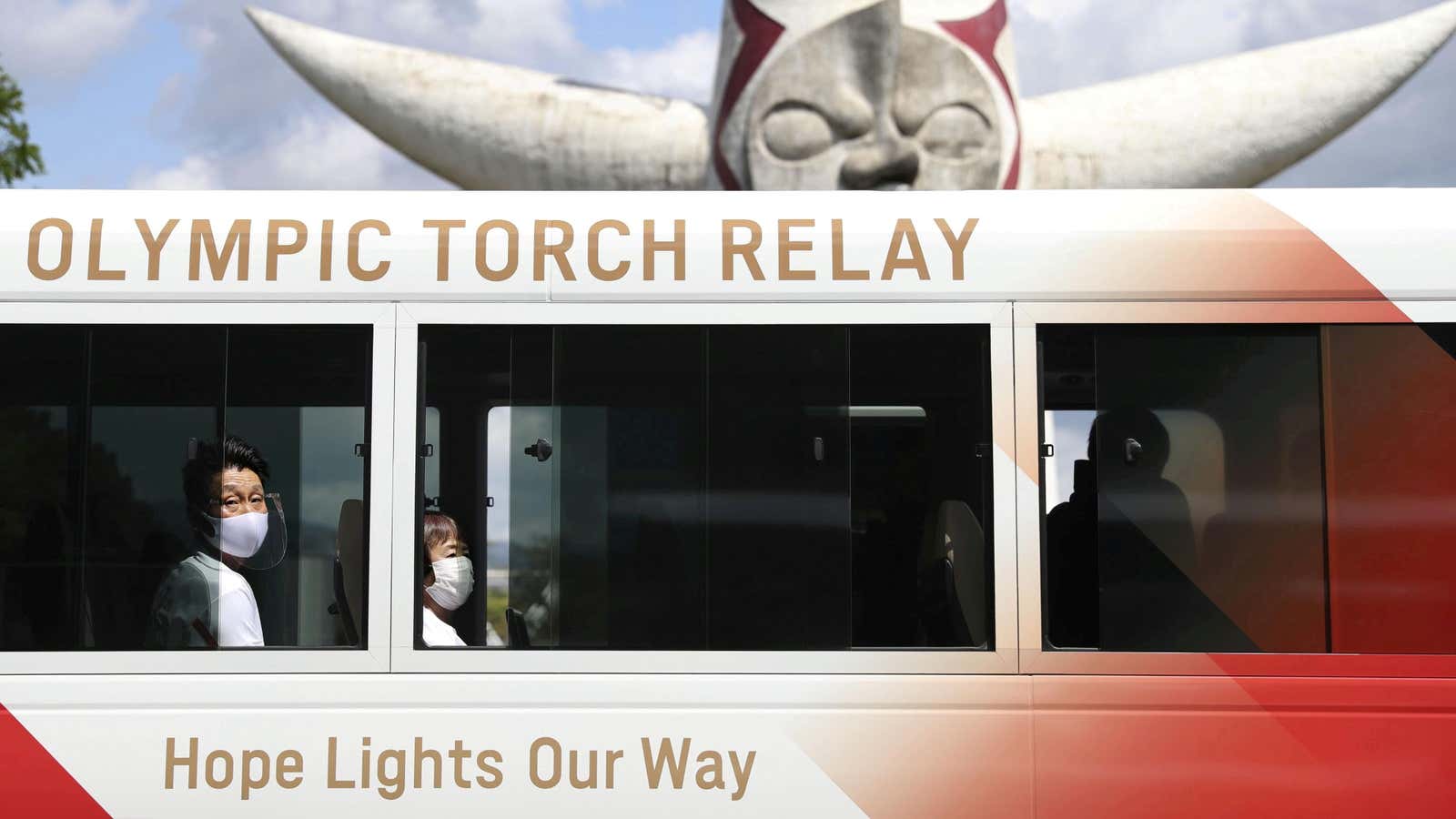

The 11,000 athletes in town, along with coaches and media have been forbidden from using public transit unless absolutely necessary. They may only use dedicated buses or taxis established to transport participants along a specific Olympic Route Network that connects competition venues, training areas, and the Olympic village. Some of these vehicles include a new Toyota self-driving electric vehicle, which was unveiled in 2019 specifically for the games.

Even with extensive testing and quarantining protocols in place, visiting athletes are not allowed to go to tourist areas, restaurants, and gyms, and are discouraged from being in contact with Tokyo residents. Quartz staff in Tokyo reported that so far, the presence of foreigners for the games hasn’t had a significant impact on everyday life. Train schedules remain the same, and everything is “business as usual.”

Some measures remain relevant

Even with firm restrictions and fewer visitors than anticipated, some changes put in place to manage traffic on Tokyo’s roadways have still proven effective. On roads within the Olympic Route Network, signs and road markings have been created to create priority lanes for Olympic vehicles. As of July 19, higher tolls are in effect on the Tokyo Metropolitan Expressway to help manage congestion. Until the end of the games on Aug. 8, the toll for private vehicles on the highway will be ¥1,000 ($9) higher during most operating hours.