Is US inequality shown by the number of people who earn their living guarding other people’s stuff?

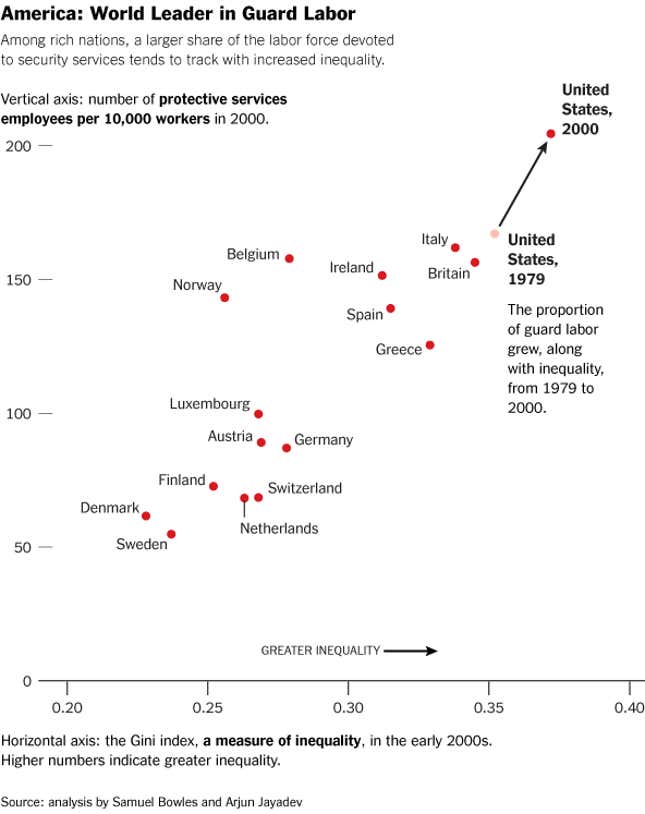

Two economists argue that “guard labor” is an indicator of inequality, highlighted by this chart showing the correlation between the two trends:

Samuel Bowles and Arjun Jayadev suggest that the connection isn’t good for the US economy: Too many people are wasting their productive time guarding other people’s wealth, while in other countries, social norms and equality suffice to do the same job. It’s a compelling argument, especially when you consider, as they do in their broadest definition, that 5.2 million Americans were working in 2011 as guard labor, in the armed forces, or producing weapons. With all this focus on guns, there is less labor focused on butter.

But that great chart above is a little misleading because you get the impression from the article that we’re mostly talking about rent-a-cop security guards wearing ill-fitting blazers. If you look at where they get their specific numbers, it turns out that Bowles and Jayadev are actually talking about the category “protective services occupations” as the US government construed it in 2000, a category which includes security guards and police officers, but also firefighters, detectives, and animal-control officers. Private security guards are only about a third of this count in the US.

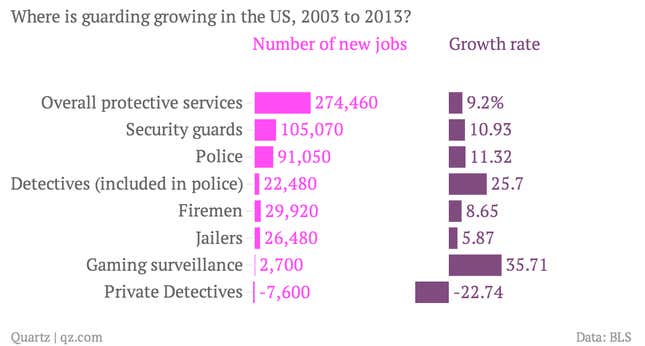

Consider this: From 2003 to 2013, the number of workers in “protective service occupations in the US” grew 9.2%, with 274,000 new jobs created. Just under 40%—105,070—were new security guard jobs, and that number didn’t grow as fast as the number of actual police officers. Here are some selected examples from the last decade:

You can come up with reasons for growth in these occupations that don’t rely on inequality, but just affluence. There’s more need for “gaming surveillance”—casino security—in a country where more people can afford to gamble, and more investment in criminal investigation, rather than street patrols, in economies where they can spend more on sophisticated law enforcement. Investments in fire safety may come from similar reasons, although there are good arguments that Americans aren’t using our firefighting labor very effectively. The rising number of security guards may reflect liability conscious sports arena owners rather than huge growth in gated communities. Meanwhile, the drop in private detectives may be a sign of lessening inequality, at least if all the film noir movies involving wronged heirs and wealthy playboys are to be believed.

That’s not to say there’s not an important point in this argument: The real waste in labor productivity that the authors identify may be the prison industrial system, where the number of imprisoned Americans and the number of people paid to guard them keeps growing even as crime rates go down.