When Chinese president Xi Jinping visited Xinjiang this week, two months after an attack by suspected Uighur Muslim separatists left 29 dead, he reminded a number of observers of another world leader taking a tough approach to an attack on domestic soil.

Xi called the autonomous western region where the government believes separatists are waging a war for independence China’s “frontline against terrorism.” He said, ”The situation is grim and complicated. The local level police stations are fists and daggers.”

Xinjiang, home to a Turkic-speaking minority with closer cultural and ethnic links to Central Asia than China, is important to Beijing. The region produces about one-third of China’s cotton, and contains large oil and gas reserves. The northwestern region briefly achieved statehood in the 1930s and again in the 1940s, but has been under Beijing’s control since then.

Xi’s remarks came during his first visit to the southwestern Chinese region since a bloody knife attack by masked assailants injured 140 at a train station in what officials called “China’s 9/11,” after the attack on New York’s World Trade Center and the US Pentagon in 2001.

The government says the train station assailants were militants from Xinjiang. Officials also labeled an incident in October—a jeep that crashed into a crowd of tourists in Tiananmen Square in Beijing—an “organized and premeditated” terrorist attack. And since then, the terms “terrorism” and “anti-terrorism” have become consistent catchphrases in official rhetoric. Xi has spoken of anti-terrorism at least 15 times since the Xinijang attack, according to the People’s Daily.

Measures to show the government’s resolve range from serious—a Chinese man who bombed communist party headquarters in Shanxi province has just been sentenced to death—to the more ridiculous. This month, officials in Xinjiang offered money to people with information on suspicious residents including those “wearing beards.”

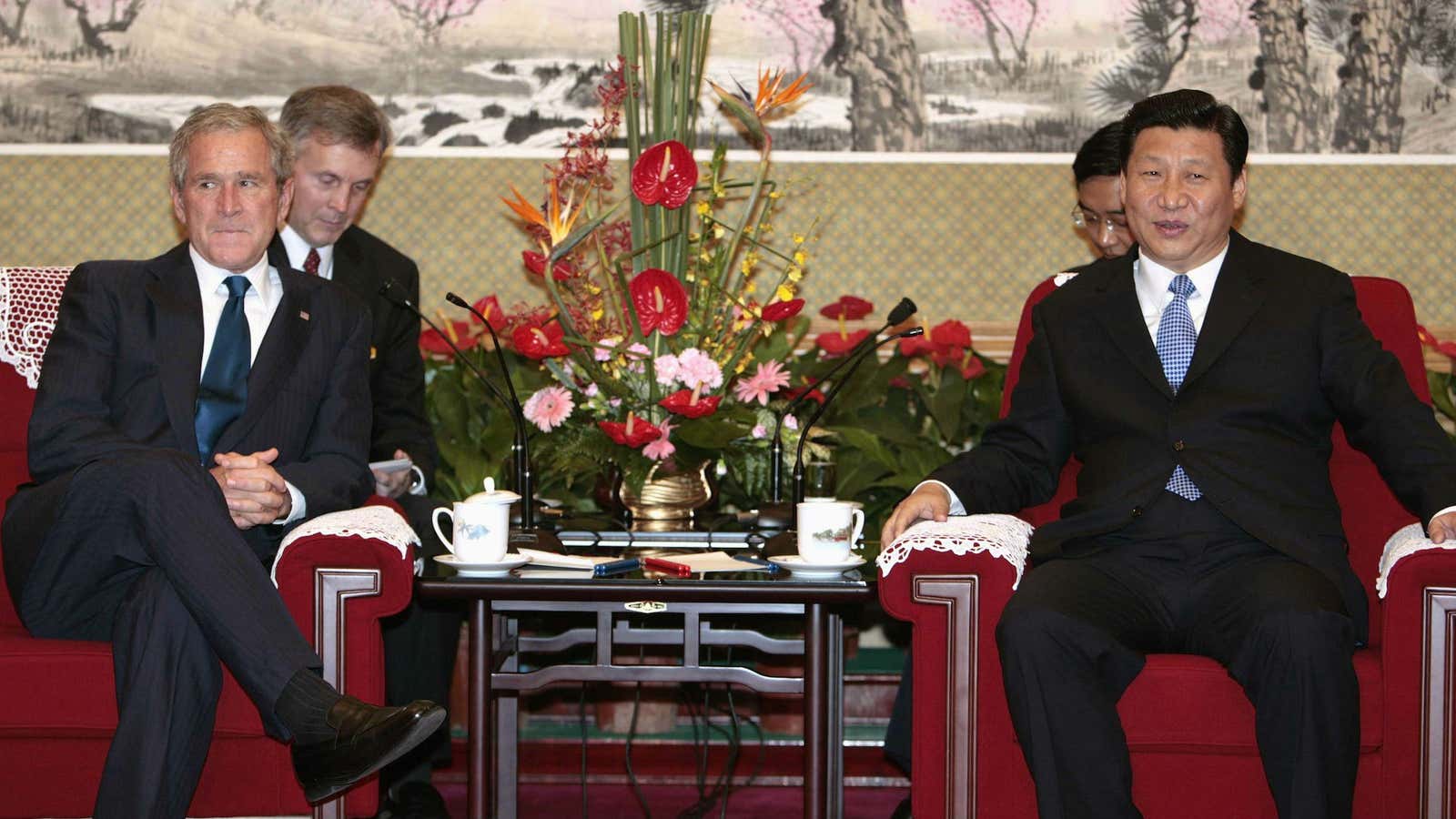

The most worrying aspect of China’s campaign is whether officials will use the latest spate of violence as a justification for disregarding civil rights in the name of fighting terrorism. After the 2001 attacks in New York, human rights groups like Amnesty International worried that China, which joined the US as an ally in the global “war on terror” would frame crackdowns on the region as part of that campaign.

Of course, China’s hardline stance toward the region dates back to before 9/11. In 1996, China implemented a “strike hard” campaign, an effort to root out all forms of separatism in the country through economic and cultural integration. Critics say the policy has instead fueled discontent and radicalized elements of a formerly peaceful independence movement. Skirmishes between Uighurs and police and Han Chinese have ended in hundreds of deaths in recent years.

This campaign is getting a new lease. Police presence in Xinjiang has been ramped up, as has a propaganda campaign to demonstrate the strength of local police. And so far, Xi’s solution for peace in the region—some experts believe that tensions in Xinjiang are because locals feel marginalized, not because they want independence—is to teach more Mandarin to non-Han residents.