There’s something very wrong with the tiny pteropods of the Pacific northwest.

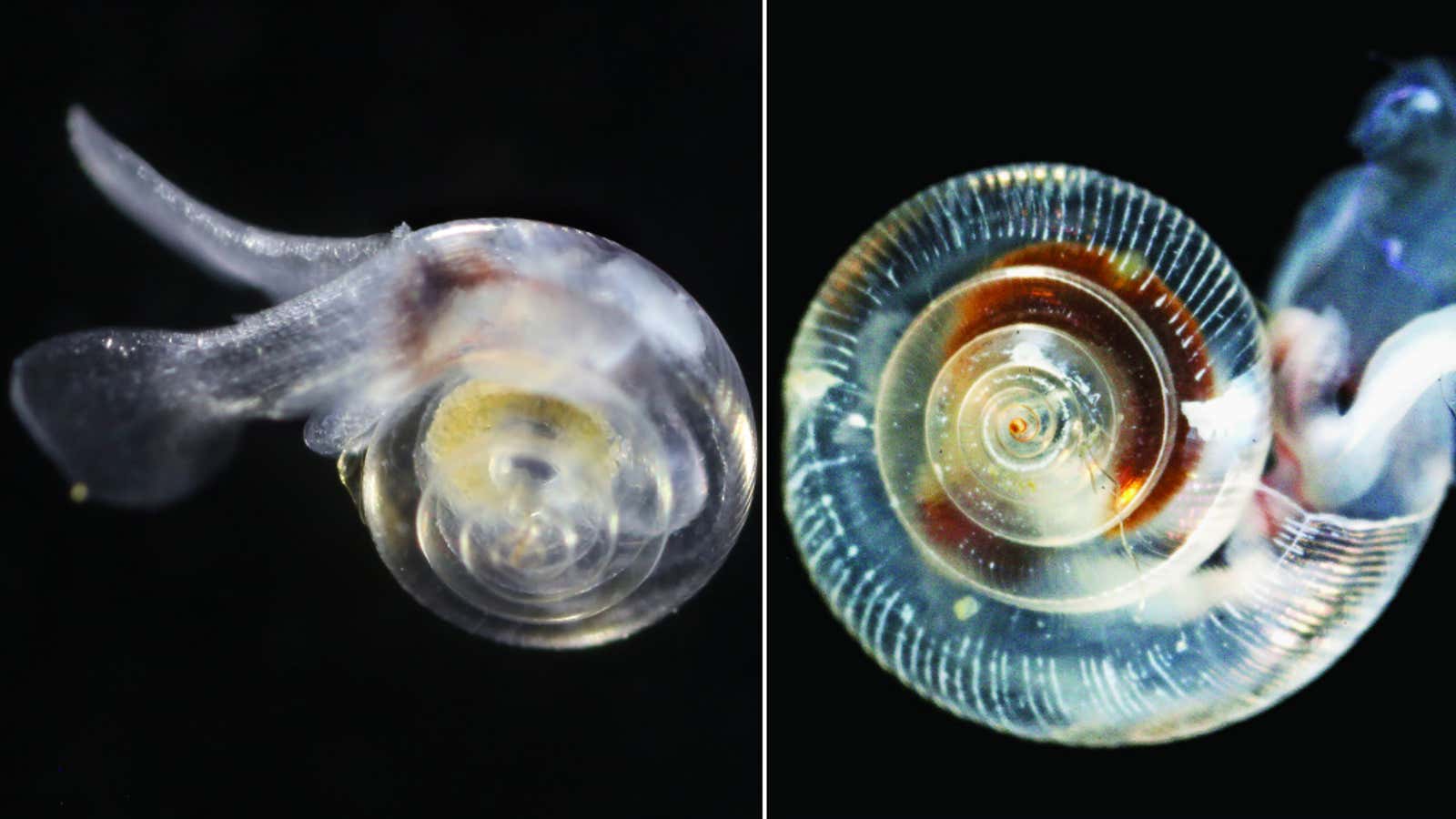

The usually smooth shells of these translucent snail-like creatures, which are also called sea butterflies, are turning up pocked and scarified, as though something were corroding them. In fact, recent research (paywall) found that more than half of pteropods sampled had severely damaged shells. Here’s a look:

This surprised the scientists who carried out the study.

“We did not expect to see pteropods being affected to this extent in our coastal region for several decades,” said William Peterson, an oceanographer and one of the paper’s co-authors.

They did expect some degree of damage. The culprit, carbon dioxide that collects in the ocean, lowers the water’s pH, making it more acidic. Because colder water tends to store CO2 in higher concentrations, the chilly upwells typical off the North American coast have always dinged up pteropod shells a little. On top of that, the researchers anticipated a somewhat higher rate of corrosion due to the steadily rising abundance of atmospheric CO2, of which the ocean absorbs 30-40%.

But researchers estimate that the prevalence of pteropods with severe shell dissolution has more that doubled since pre-industrial times. That implies the swath of sea from California to Canada—a vital pteropod breeding ground—is turning into an acid bath at an alarmingly rapid clip. Peterson and his colleagues project that by 2050, as many as 70% of pteropods will have acid-ravaged shells.

As you can see in the YouTube clip above, worn-away shells make it harder for these little guys to swim and, therefore, to evade predators. They also need solid shells to reproduce. And though they can patch their shells, doing so takes a lot of energy, making them all the more vulnerable to attack.

While today’s Pacific northwest might be a buffet for pink salmon, mackerel, herring and other fish that see the sluggish sea-going snails as an easy snack, in the long run that could cause pteropod reproduction rates to decline. If the pteropod population starts to decline, all those fish that rely on them for food will start to die, too.

And it’s not just pteropods. Mollusks and other creatures at the same level of the food chain are struggling to survive in the intensifying burn of acid oceans. What the pteropod shell crisis tells us, says co-author Nina Bednarsek, a research fellow with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, is that we’re behind the curve: Not only in grasping what acidification is doing to economically-important fishery stocks, but also how it might reshuffle the Pacific Northwest’s entire marine ecosystem.