Why the iPad is (still) the future of Apple

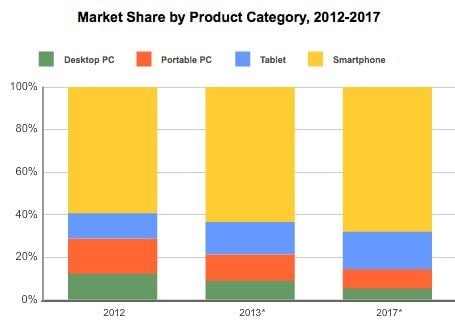

Here is a surprisingly controversial statement: The iPad is going to be huge. Tablets, in general, will someday soon not merely outsell personal computers, but actually replace them, even in businesses, and in productive capacities for which people currently believe “only a PC will do.”

Here is a surprisingly controversial statement: The iPad is going to be huge. Tablets, in general, will someday soon not merely outsell personal computers, but actually replace them, even in businesses, and in productive capacities for which people currently believe “only a PC will do.”

Quartz’s recent coverage of Apple has outlined in detail the problems Apple is having selling iPads. But this is a story about what comes next—a future in which the company’s current tablet woes are revealed to be, essentially, a temporary lull in a long-term trend of potentially huge growth.

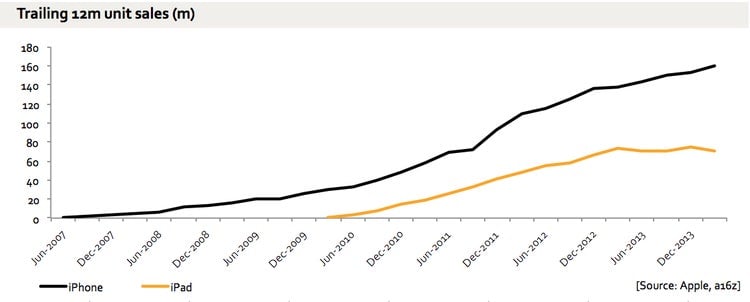

Just a year ago Apple was seeing explosive growth in sales of the iPad, and pundits declared the iPad—not the iPhone—the future of Apple. But over the past year, as Andreessen Horowitz partner Benedict Evans has outlined, iPad sales have been essentially flat.

This has led some analysts at banks to issue dire warnings about the future of the iPad and Apple. Citi is especially bearish on the future of the iPad.

Others disagree. Their perspective: In the first four years of their existence, humanity purchased iPads at nearly twice the rate that it purchased iPhones during their first four years.

That’s 210 million iPads. If the iPad is a personal computer, Apple is the single largest manufacturer of PCs, even excluding the number of Macintosh computers it sells. If the iPad were a business unto itself, it would be a Fortune 100 company.

Does that sound like a company that’s “blowing it”?

iPad sales growth may have stalled, but more people own iPads than ever, and that growth rate hasn’t slowed

If you want to understand what’s governing iPad sales, you have to reconcile two seemingly contradictory bits of information. You have to understand, in essence, why the number of people who find iPads useful is still growing explosively, even as the number of iPads sold each quarter has stalled.

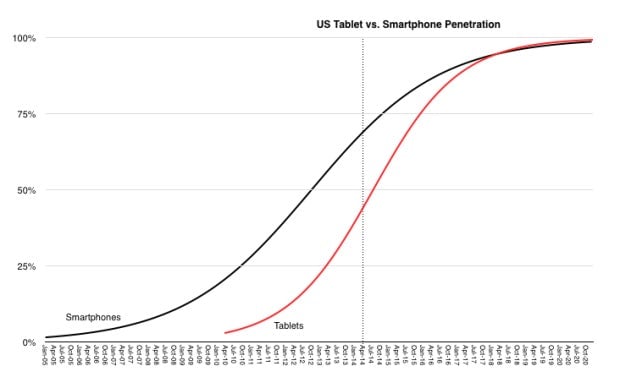

The thing about the adoption of tablets—or pretty much any shiny new thing—is that if you see very quick early adoption, the product almost always goes on to ubiquity before too long. That pattern suggests there’s still significant growth ahead for tablets from where they are now, since they’re not ubiquitous despite fast early growth. Here’s how mobile analyst Horace Dediu puts it:

Historically, products which become ‘mainstream’ or widely adopted follow an S-curve during that adoption. The curve is remarkably predictable given a limited set of points….We are fortunate that data also exists for tablets.

And here’s what that S-curve of adoption looks like. It puts saturation of the market for iPads sometime around 2018, not 2014.

Yet iPads sales have “stalled” for the past year—so how is it possible that more and more people have come to own one?

There’s a hint in Apple’s last earnings call. CEO Tim Cook said that “over two-thirds of people registering an iPad in the past six months were new to iPad.”

And there’s one more factor here to consider—iPads just last a lot longer than phones, and are replaced less frequently. They’re less likely to be dropped, stolen or lost, and people don’t use them as compulsively as they do phones, so their batteries last longer as well. Even the ways people use tablets—watching video, casual web browsing—are less demanding than the dozens and dozens of apps and attendant scenarios in which people use their phones, which means an iPad 2 is today pretty much as useful as the day it was purchased.

The mathematics here aren’t complicated: If iPads last a long time, and Apple is still selling a respectable 15 million to 20 million per quarter, most of them to people who have never owned one in the first place, the rate at which Apple sells iPads can stall even as iPads continue to take over the world—or at least the US and other rich markets.

Smartphones killed tablet growth, but not for long

There’s an important unknown that must be addressed, and it’s probably a drag on how many iPads (and tablets in general) are being sold: smartphones.

Consider the job that tablets do, rather than the device itself. If the point of a tablet is to watch videos, read stuff, browse the web, and be in general more available and easier to use than a PC—guess what, our smartphones already do those jobs, and in some cases, better than tablets do.

Much has been made of the possibility that larger phones will eat a portion of the tablet market, as if it were merely screen size that matters. And perhaps it does, for some users. But, for the majority of people, it’s apparent that the smartphone’s always-on connection to the internet, via a mobile network, far outweighs whatever additional utility we gain from a larger screen.

Just two years ago, nine out of 10 tablets sold were Wi-Fi only, meaning that you couldn’t connect them to a cell network at all. Because of the long replacement cycle of tablets, most of those tablets are probably still in use. More recent numbers on the proportion of tablets sold that include an LTE radio (which allows them to connect to a cellular network) are hard to come by, but the proportion probably hasn’t changed substantially, since a connection to a cell network still involves a substantial price premium over a Wi-Fi-only tablet—as much as $100—and then there’s the additional expense of yet another monthly data plan, although carriers are getting creative about making tablets add-ons to existing plans.

Tablets have been neglected by developers

Imagine if developers of apps for smartphones couldn’t guarantee that the device their software would run on would always be connected to the internet. Startups such as Uber, Instagram, and Waze simply wouldn’t make sense. Is it any wonder that smartphones have drawn most of the attention of developers?

Chris Dixon, also a partner at the tech-focused venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, says that a vanishingly small proportion of the apps he is pitched are designed specifically for the iPad. But what if the iPad had launched before the iPhone (as Apple had originally planned when it began exploring the multi-touch interface back in 2003)? Dixon posits that if the iPad had launched before the iPhone, it would have captured much more developer interest than it has, and we’d be seeing many more dedicated iPad apps that take advantage of its larger screen size.

On Android, the situation is worse—an even-greater proportion of apps lack a tablet mode at all, and are merely larger versions of their smartphone selves.

Tablets deserve their own operating system—or at least a distinct user interface

Tablets are the only class of consumer computing device that doesn’t get its own operating system. PCs have Windows, OS X, and an infinite variety of Unix and Linux variants (Ubuntu, Chrome OS, etc.), all of which are tailored to work with devices such as full-size keyboards, mice, drawing tablets, etc.

Phones, too, have operating systems that just keep getting better. Apple and Google are locked in a battle of feature and usability one-upmanship designed to make their phones ever more indispensable. As a result, the smartphone is a technology so transformative that it makes the tablet look boring by comparison.

But why is that? One reason, outlined above, is that most tablets still suffer from a lack of connectivity options. What’s the point of a “mobile” device that requires you to be in a home, office, or coffee shop that has Wi-Fi? Another reason is that tablets are still not as good as notebook PCs at most productivity tasks. Granted, Microsoft just released Office for the iPad. But using an operating system designed for a device with a four- to five-inch screen for tasks we’re used to accomplishing in a modern PC operating system is still a headache. A recent survey by IDC found that only 8.7% of tablet buyers intended them to be replacements for their laptops.

The result is that iPads, and tablets in general, are squeezed on both sides, by smartphones and PCs.

This has led some to conclude that what tablets need is to become more like PCs—with windows, multitasking, and the ability to save and manipulate files as one would on a desktop. But this misses the greatest advance of Android and iOS, which is that we can often accomplish tasks faster in purpose-built environments, like single apps with stripped-down interfaces. Desktop operating systems, with their myriad options, toggles, buttons and drop-downs, are in some sense design failures and obselete artifacts, embodying the victory of engineers over users.

But what does a tablet OS even look like? Is it a souped-up version of a phone’s operating system, or a stripped-down version of a desktop operating system?

While we don’t know the answer to that question, there are rumors that Apple is hard at work on it. KGI analyst Ming-Chi Kuo claims to have inside knowledge indicating that Apple’s rumored extra-large iPad, which at 12.9 inches diagonally is as big as a medium-size notebook PC, is real.

Kuo also hypothesizes that at these dimensions, the “iPad Pro” will finally get a user interface that isn’t just a gigantic version of what’s already familiar on the iPhone.

“With the 12.9-inch iPad, we think Apple will come up with a new user interface that’s more innovative and intuitive, so that input will be as efficient as a device with a keyboard,” Kuo writes.

This might be wishful thinking. And the resistance of users to Windows 8—a tablet-centric redesign of Microsoft Windows—indicates it could flop. But if anyone can figure out how we’ll interact with a new category of device, it is, as ever, Apple.

Tablets are already uniquely useful for certain tasks, and new interfaces will only make them more essential

The combination of an iPad with a credit-card reader from Square (or one of its competitors, such as eBay) is a potent one. With a single device and a trivial add-on, merchants can go from complicated, bulky, ugly, cumbersome, expensive point-of-sale terminals to self-contained devices that can also help merchants get to know their customers better, by allowing for rewards programs and payment through means other than credit cards.

A cash register is an object for which both customer and merchant really do need a larger screen. And there are other cases. Try making a sales presentation on an iPhone instead of a full-size iPad, for example. In education, the replacement of textbooks and the development of new teaching aids require something approximating the dimensions of a sheet of printer paper. Apple claims to have a 95% share of the US education market for tablets.

As tablet interfaces evolve, two things will happen to move more tasks from PCs to tablets: First, web-based tools and new apps will replace tasks that currently can only be done with PCs (such as sophisticated slide presentations) with tasks that can be done just as well or better on tablets instead (for example, sending out a link to a real-time web-based customer relations dashboard). Second, tablet interfaces will inevitably become, if not more PC-like, then different in ways that make it easier to switch between applications rapidly, and move data and files between them.

The future of tablets interfaces is going to get weird—in a good way

All tablet-specific applications have come about because developers recognized they could create apps that were uniquely better on a larger touchscreen. What happens when Apple, and eventually Google (through Android) facilitates this process by making a tablet interface that capitalizes on the strength of tablets—for example, apps that have more than one “window,” and touch interfaces that reward two-handed interaction?

There’s a moment in the film Avatar when a character does something with a tablet computer that seems both futuristic and inevitable. In a control room on an alien world, the character interacts with something on the screen of what looks like a typical PC, and then he swipes at the object, sliding it from the PC screen onto a tablet he’s holding in his other hand.

Because it’s fiction, this interaction is completely seamless. But it raises a question—why can’t we simply “grab” whatever we’re manipulating on a PC and “toss” it onto a tablet. If you’re in a web browser, you can already sort of do this in Google Chrome. It allows you to open tabs that are open on any other device on which you’re using Chrome and are logged in to Google. But it’s a cumbersome process compared to the one Hollywood imagined.

A future in which tablets are just another screen is one in which they’re both more useful than they are now and more ubiquitous, even though in such a scenario, they appear to be doing less than they are now, which is functioning as standalone computers. But this is just one possibility—it’s likely that tablet interfaces will become more complicated and self-contained as well, which leads us to our next scenario.

How tablets eat the market for notebooks

I’m willing to bet that eventually, Apple will make a combination tablet and laptop, otherwise known as a “convertible.” As usual, what has held them back is that the technology just isn’t there yet. Making a device that can be reconfigured to function either as a notebook or a tablet adds weight, and given the present state of tablet interfaces, not a whole lot of utility.

At this point the debate over what a tablet even is gets murky. Is a touchscreen notebook that can transform into a tablet really a tablet? What if a tablet has a dedicated hardware dock for plugging into a keyboard? And what if all we ever get from Apple is a tablet that works really well with an external wireless keyboard?

I think all of these questions miss the point: What matters isn’t whether the tablet of the future will require a dedicated keyboard for some tasks—undoubtedly, for things like email, it will. What’s significant is, rather, that the tablet will become the dominant form factor, however it interfaces with peripherals like keyboards. What’s more, operating systems will become tablet-centric rather than notebook centric, or at least tablet-centric operating systems will outsell legacy operating systems designed for notebooks and desktops.

This is one area where a competitor might get to a functional solution first—already, hardware makers are experimenting with curiosities like Android notebooks. And journalist Kevin C. Tofel has proposed that a Chrome OS-based tablet might appeal to people who have so far avoided Google’s attempts at a web-centric operating system.

Even if Apple never creates a convertible iPad/notebook—perhaps an iPad Pro plus a keyboard case will be sufficient for that niche—other developments, like a drop in the price of the LTE radios required to connect a tablet to a cellular network, will continue to make tablets more functional.

Tablets that, through a combination of new hardware and reimagined software, can do things no tablet could do before will allow people to accomplish on touchscreens more of the tasks they currently accomplish on PCs. More importantly, these devices will be better able to accomplish the jobs we ask PCs to do for us, even if they require people and businesses to adjust their workflows to touch interfaces, new kinds of software, and ways of doing things that revolve around the cloud.

The potential upside for Apple is huge—but competition looms

Most of the tablets sold in the world today are cheap in every sense of the word—$100 and less, churned out by factories in Shenzhen, China using parts that are two and three generations behind the latest devices from Apple, Samsung, ASUS, and other manufacturers. On the surface, the way the iPad has ceded global market share to these tablets—even in the US, Apple is at about 36% market share—might make it look like the iPad is poised to be disrupted in the classic fashion, by a good-enough competitor. But so far that’s only for the jobs that tablets have historically been limited to.

If all you need is a screen on which to watch videos, play games, and browse the web, you might as well buy a tablet sold at cost by Google, Amazon, or even the British supermarket chain Tesco, and pay around half what Apple is asking for its tablets.

This means it’s up to Apple to make the case that the iPad is useful in ways that its cheaper competitors are not. And if the rumors about a future iPad Pro are true, it seems reasonable to assume that Apple is much further along in its thinking about the utility of tablets than all the pundits and analysts on the planet—including this one.

One potential threat to Apple is that Google continues to be more forward-thinking about how to allow users to access Google’s cloud-based software on any device. Google makes it relatively easy to use a tablet as a second screen, opening tabs on a tablet that are already open on any other device. And now, with the inexpensive Chromecast device that plugs into a TV, people can “cast” video and a few other apps from a tablet or a smartphone to a large screen.

On the other hand, Google’s apparent disinterest in usefully customizing Android for tablets means Apple still has an opening to redefine how we use touchscreen devices. We’ll always need something like a PC to create things as well as consume them, but an ever-larger proportion of those tasks will be taken over by high-end tablets, where Apple is, at least in rich countries, still very much in the lead.

Insofar as tablets are PCs, Apple’s flat sales of iPads indicate that people don’t need as many PCs as they once did. And with tablets still in their infancy, the assumption that tablets won’t continue to become more ubiquitous, and that Apple won’t be dominant in that process, is a failure of imagination.