New data out from China’s central bank shines some light on the worrying spread of shadow banking—as lending conducted off bank balance sheets is known—throughout the economy. Not only have city-level banks been on a shadow-lending spree, but so too have Chinese non-financial companies.

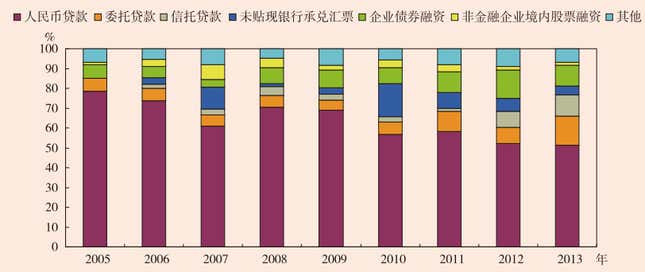

First, there’s recent data on “entrusted loans”—credit issued between two companies, a practice that’s illegal unless a bank arranges the loan. As the People’s Bank of China noted in its recent report on financial stability, “entrusted loans” are contributing to a sharp rise in shadow credit’s share (link in Chinese, pdf, p.25) as a proportion of total lending:

However, banks often broker these deals to hide risk, using this complicated credit structure to skirt the ban. How does that work? Say a real estate company comes to a bank for a loan, but is in too dire financial straits to be eligible. The bank can sidestep risk-management standards by issuing a loan to a company considered financially stable—often a state-owned enterprise (SOEs)—which turns around and re-lends that capital to the risky borrower at a much higher rate, with the bank charging a fee. Banks say that they won’t assume the repayment risk if the loan sours.

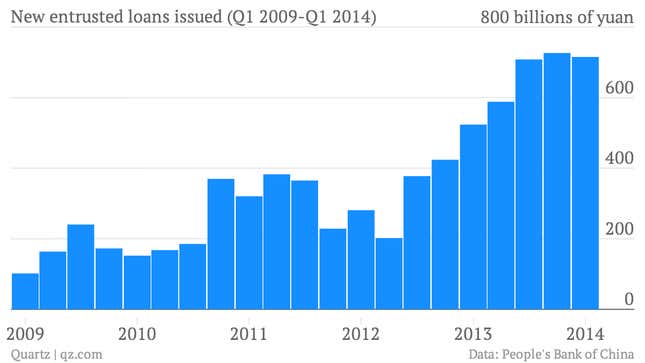

So how much money are we talking here? The Wall Street Journal reports (paywall) that China Construction Bank (CCB) had issued 1.4 trillion yuan ($220 billion) in outstanding entrusted loans at the end of 2013. Overall, Chinese banks recorded 715.4 billion yuan ($115.4 billion) in entrusted loans in the first quarter of 2014. (Note that though banks tend to record entrusted loans that they broker, sources say they don’t always do the same for loans they facilitate that are arranged between companies.)

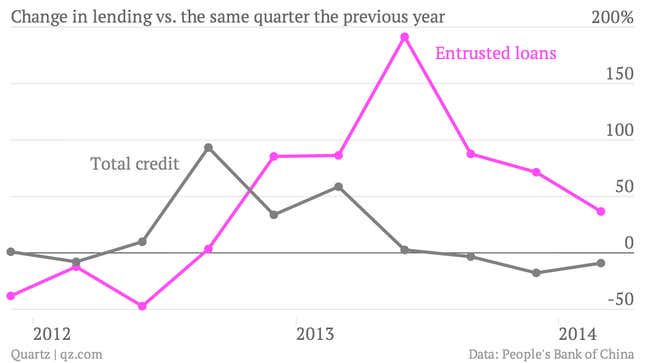

As you can see in the chart above, that’s roughly the same as the previous two quarters. That means that, at 36%, the pace of annual growth is actually coming down. However, compared with China’s slowdown in new credit, entrusted loan volume is still rising quite quickly:

The second disquieting signal of China’s financial health comes from small city-level banks, where shadow lending is a growing piece of the pie. These banks tend to be dominant lenders in their hometowns, lacking the national reach of big state-owned banks such as Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) or China Construction Bank (CCB). A Financial Times analysis of 10 of these banks (paywall) found that, at the end of 2013, shadow lending made up 23.3% of their total assets, compared with 14.3% in 2012.

Most of this credit has been issued to companies ineligible for official loans due to their struggle to generate steady cash flow—for example, local governments, real estate developers, or coal and steel firms. Still, the regulators don’t deem these smaller banks major systemic risks. At China’s four big state-owned banks, which account for about half of banking assets, shadow loans make up a much smaller portion of loans.

However, as with most aspects of Chinese shadow banking, what’s worrying isn’t necessarily the absolute number, but the rate of change. The fact that shadow credit as percentage of total assets at city-level banks leapt nearly 10 percentage points in a year signals how quickly such risky lending is catching on—even as the regulators say they’re cracking down on those practices.