The future of the US electric grid will be on the line on Sept. 30, when the House of Representatives votes on a $1 trillion infrastructure bill that is at the heart of president Joe Biden’s agenda.

The bill includes about $27 billion for the grid, including loans to utility companies to invest in climate change protections, cybersecurity and software upgrades, and funding for transmission projects.

But the bill’s most important provision for the grid isn’t about money. It’s a tweak to an obscure law that should make it easier for developers to build long-distance, high-voltage transmission lines, a necessary ingredient for a grid with lots of renewable energy that has been stymied by jealous utilities. But it doesn’t go far enough, some experts say, to truly clear the path to one of Biden’s goals: a carbon-free grid by 2035.

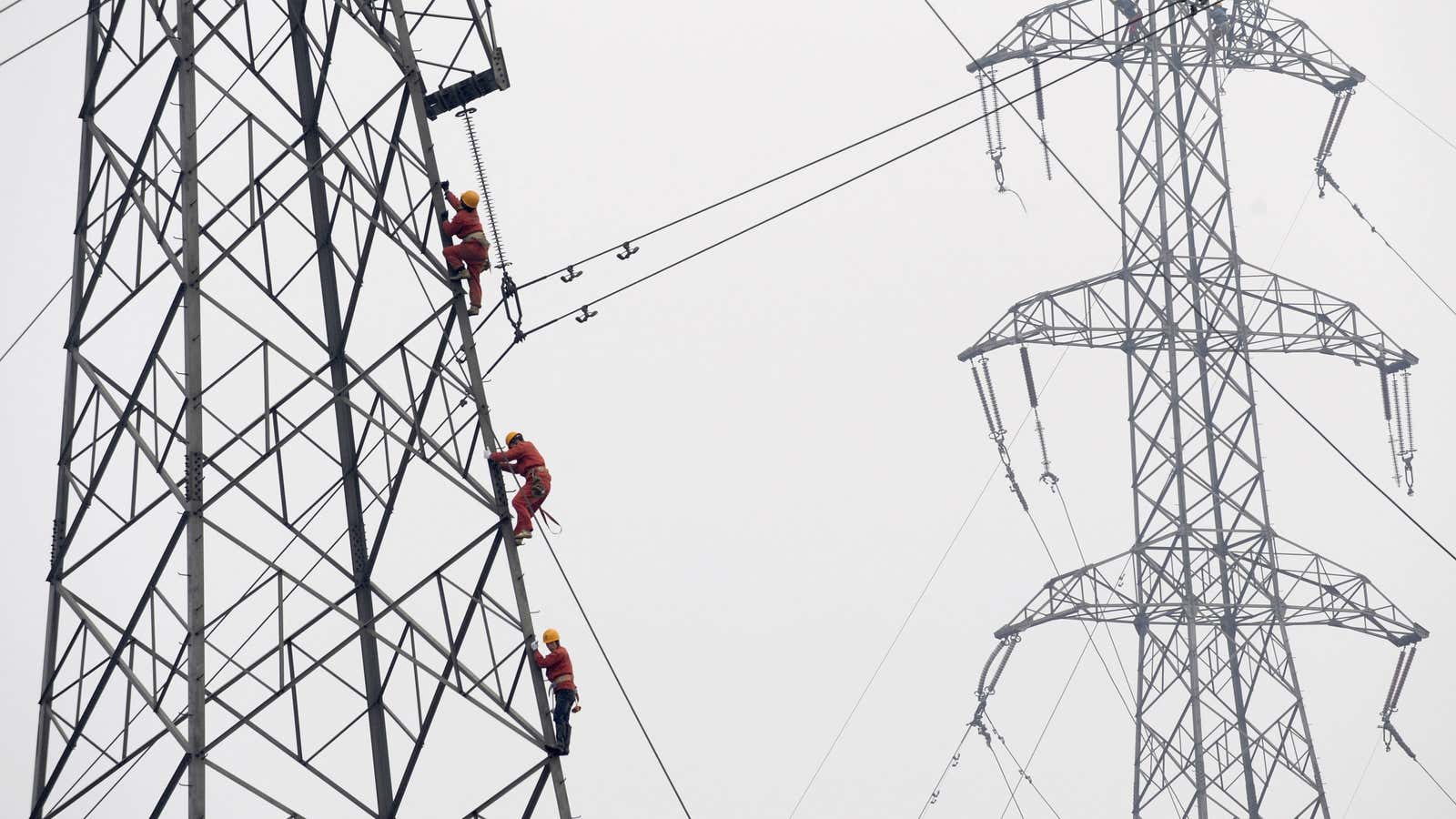

New transmission lines are essential to the clean energy transition

To prevent blackouts as the grid relies more on intermittent solar and wind energy, utilities need to be able to move electrons quickly over long distances to match supply and demand. Transmission lines in the US are almost entirely regional, and do not have the capacity to move large volumes of electrons long distances without high rates of loss.

A few high-voltage lines are in the works, but are far behind the scale of China, which has the lines to essentially move a power plant’s worth of electricity across the country with minimal losses. High-voltage transmission in the US must increase by 60% in the next decade, according to the World Resources Institute, at a cost of $360 billion.

The main reason for the delay is that the federal government—specifically the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC)—can’t overrule state and local planning commissions on where transmission lines are sited. Because these commissions are heavily influenced by local utilities that don’t want to face outside competition (as well as residents annoyed by the prospect of a new power line in the neighborhood), they tend to oppose major transmission proposals.

The infrastructure bill gives FERC more power

The infrastructure bill extends FERC’s authority, such that it can overrule those commissions. To do so, it must grant a special designation to the land in question—but the bill also expands the list of factors FERC can use to make that designation. The bill also allows the Department of Energy (DOE) to enter contracts for up to half of the power transmitted through any proposed lines, creating more certainty for investors.

All of this will make it easier for the DOE to design a grid that is more dynamic, lower-cost, cleaner, and better adapted to climate change impacts, said Steve Cicala, an energy economist at Tufts University and an expert on grid decarbonization.

But even if the bill passes, FERC and project developers will still have to jump through more hoops to approve transmission projects than they currently do for new oil and gas pipelines, Cicala said. More red tape needs to come down before enough high-voltage transmission lines can go up.

“The bill gets things flowing like mud rather than concrete, which is how they flow now,” Cicala said. “But there’s enough private sector interest in building transmission lines, if only they could only get approval for it, that streamlining this process is a lot more important than throwing money at it.”