In economics, experimentation is an elusive affair. In examining whether a school education improves the mental health of children, for example, no economist can design and run a controlled experiment. As Eva Mörk, a member of the committee that judged the 2021 Economics Nobel, said during the prize announcement on Monday (Oct. 11): “We can’t let some individuals take part in school and forbid others from going to school.”

But sometimes the world offers experiments with readymade controls, if only economists know where to look.

Mörk provided one example. Children born on Dec. 31 of one year aren’t appreciably older than those born the next day, but the former may start school a year earlier than the latter in countries where such decisions depend on the calendar year of your birth. To investigate how the school closures during the pandemic affected children, Mörk said, an economist might study a group of children who were born on Jan. 1 and who started school last year, and compare them with a control group of children who were born on Dec. 31 and started school in 2019. Set up in this way, the study shrinks the variations that might otherwise crop up while comparing older children to younger ones. In the pandemic, Mörk said, “nature has given us an experiment.”

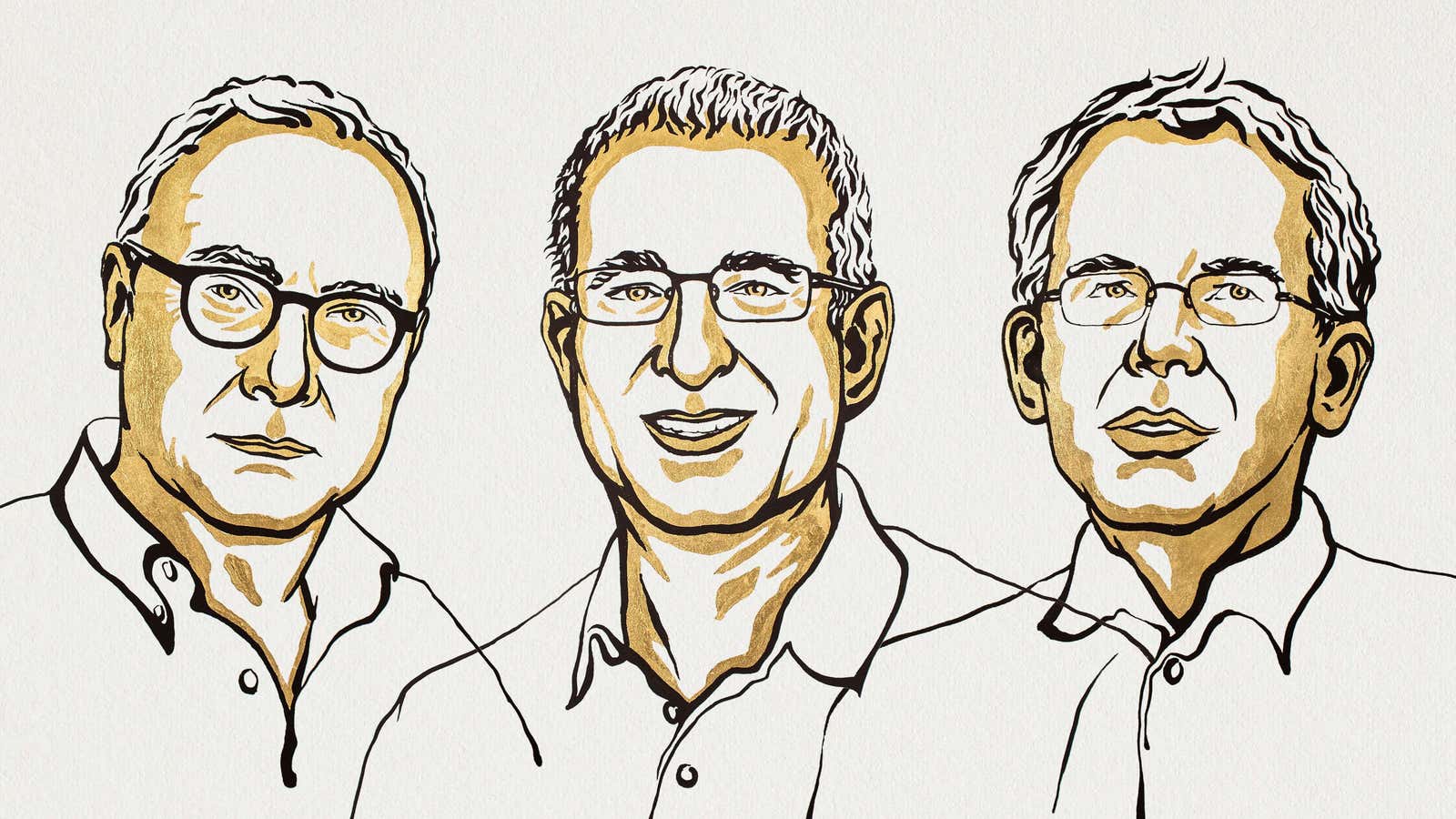

David Card, Joshua Angrist, and Guido Imbens, the three American economists who won the 2021 Nobel prize, have spent years looking for such experiments, analyzing the data from them, and drawing conclusions that can shape social policy in powerful ways.

Natural experiments in economics

In 1994, Card, an economist now at the University of California Berkeley but then at Princeton, found an unintended experiment, the results of which contested a commonly held belief in economic theory. Raising the minimum wage, many economists have argued, results in decreased levels of employment. Employers, having to pay their staff more, economize by hiring fewer people, the belief holds. In this model, the higher minimum wage is the cause, and depressed employment the effect.

To test this proposition, Card found a group of fast-food workers on either side of the New Jersey-Pennsylvania border—people who were likely to live in similar social and economic conditions, despite being in different states. In 1992, New Jersey had raised its minimum wage from $4.25 per hour to $5.05 per hour, so its fast-food workers could be compared to a control group of their Pennsylvanian peers. Surveying 410 restaurants, Card and his colleagues found no proof of a decline in employment as a consequence of the minimum wage hike; in fact, in their data, employment rose slightly.

Card’s work has also pushed back against the long-held theory that a rise in immigration adversely affects the labor market, pushing down wages and stoking competition for jobs. He found his natural experiment, in this case, in the Mariel Boatlift, when a brief change in Cuban immigration policy in 1980 resulted in at least 60,000 Cubans settling in Miami nearly overnight. The city’s labor force swelled by 7%. But Card’s research discovered no evidence of a contraction in wages or employment prospects for people who already lived and worked in Miami. Other localized natural experiments have since confirmed the impact of immigrants on the pre-existing labor market is, at most, negligible.

Economists have been cautious about extrapolating too much from these experiments. For one thing, a result in one part of the world may not always hold true in different conditions elsewhere. For another, the fact that these are unintended experiments means that economists have no control over the people being selected for study. How can economists cleanly deduce cause and effect, rather than mere correlation, if they don’t know the motivations of the people making up their data? Angrist and Imbens addressed this question by designing quantitative methods to analyze experimental data—to recognize the signals that can best establish causal relationships, and to arrive at numerical estimates of the impact of a policy upon the people being studied.

The “credibility revolution” in economics

If 2021 was the year of the unintended experiment, 2019 was the year of the intended experiment. In that year, the economists Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee won the Nobel prize for their work with randomized controlled trials. These are experiments designed such that a particular policy intervention—giving free bicycles to schoolchildren in rural areas, say—is rolled out for one group of people but not for another, similar group. The latter becomes a control group—a way to measure and test the effectiveness of the policy itself.

Both of these experimental methods are part of a three-decade-old wave of economic empiricism that is popularly known as the “credibility revolution.” Champions of the revolution argue that the field’s image had earlier suffered because it only offered theories. (One of Angrist’s papers, in 2010, was subtitled “How Better Research Design Is Taking the Con out of Econometrics.”) Using intended or unintended experiments, the empiricists like to think, confers upon economics the hard edge of a science. And evidence from such experiments can be used to counter beliefs that hollow or politically convenient; an anti-immigration politician claiming that his stance boosts his constituents’ prospects in the labor market can now, at least in theory, be called out for his questionable economics.

But the empiricists have their critics. Some argue that experiments, and randomized trials in particular, dehumanize their subjects, and others that experiments can only ever address small, specific questions rather than big structural ones. “In some quarters of our profession,” the economist James Heckman said in an interview, “the level of discussion has sunk to the level of a New Yorker article: coffee-table articles about ‘cute’ topics, papers using ‘clever’ instruments.”

But Angrist has defended (pdf) the empirical approach, pointing out that the results of well-designed experiments can advance, or even anticipate, theoretical work, and that narrow inquiries can help solve large, structural problems. The accusation is that “experimentalists are playing small ball while big questions go unanswered,” Angrist wrote. “Small ball sometimes wins big games.”