In his expansive campaign ahead of this general election, Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) high-profile prime ministerial candidate Narendra Modi has addressed 437 rallies and 5,827 public events (some using 3D holographic projection technology), and travelled 300,000 kilometres across 25 states. But as the campaign draws to a close, the talk now is about a different kind of rally—the so-called Narendra Modi rally in the stock markets.

On Monday, the key Indian equity indices—the Sensex and Nifty—both hit lifetime highs. Many analysts attribute the surge to the expectation that India will vote for a BJP-led coalition government headed by Modi, who is seen as a business-friendly leader supportive of economic reforms.

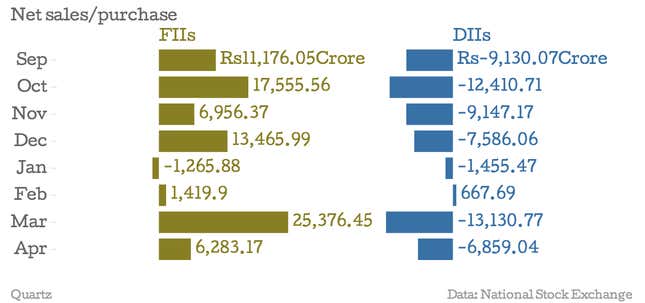

The rally is a bit more complicated than it seems. Since September, as the markets have risen, foreign and domestic institutional investors (FIIs and DIIs) have taken dramatically different positions. Starting in September, when Modi was declared the opposition BJP’s PM candidate, FIIs have been net buyers in Indian markets (except for January) and DIIs have been net sellers (except for February). For every single trading day so far in May, DIIs have been net sellers and FIIs have been net buyers.

For three months prior to September, FIIs were net sellers in India, partly on fear of liquidity constraints stemming from a US Federal Reserve proposal to curb a stimulus program. In September, India’s central bank also got a new governor in the well-regarded economist Raghuram Rajan, who helped stem steady erosion in market sentiment and the value of the currency.

But as opinion polls started predicting a greater lead for a BJP-led coalition with each passing day, the improving market confidence came to be attributed to the expectation of a Modi victory, much to the annoyance of the government’s policymakers. In December, when Goldman Sachs upgraded its India rating, it called the report “Modi-fying Our View”.

Domestic institutional investors are largely made up of insurance companies and mutual funds. Dhananjay Sinha, who heads research at Mumbai brokerage Emkay Global, said there was “disproportionate enthusiasm” among FIIs. “DIIs have a more realistic perspective. They know how difficult it is for a new government to turn things around. And FIIs have liquidity, and DIIs got an opportunity to book profits. So they must be utilizing it,” he said.

Devangshu Datta, a New Delhi-based technical analyst, said the diverging behavior of FIIs and DIIs was puzzling but could be due to multiple factors. “Domestic institutions are far more skeptical about opinion polls. Net redemptions might be higher and mutual funds might be forced to sell,” he said. When mutual fund redemptions outpace investments, fund houses come under pressure to exit their equity positions.

FIIs now own 22.3% of the 1,200 companies listed in the National Stock Exchange. And despite the record run in India’s stock markets, the situation could very quickly change course. India’s equity markets have a history of rallying ahead of general elections, and sharply correcting if the country votes differently from their expectations. TV channels will broadcast exit polls results after 6pm today. So Tuesday could be another action-packed day: Analysts have warned that an ambiguous electoral verdict might spark off heavy selling, roiling the markets and the currency.