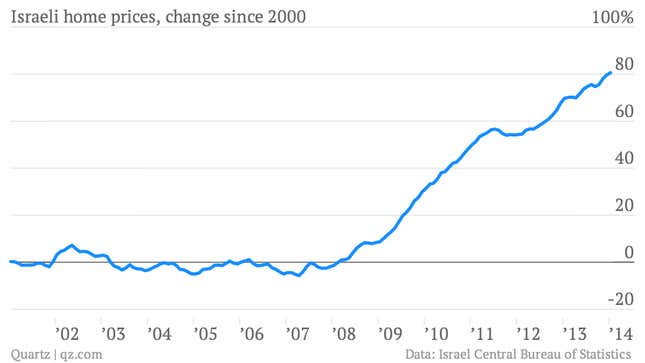

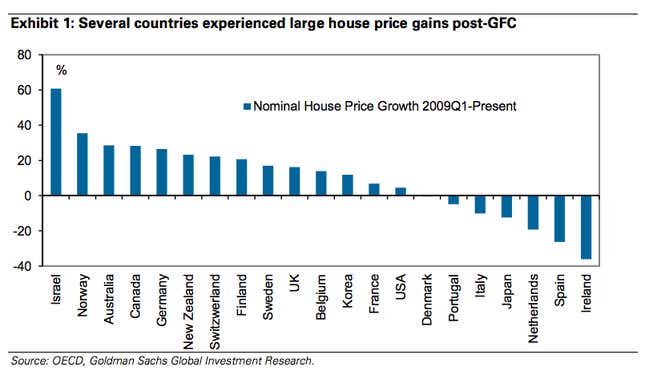

Israel’s housing market is clearly one of the world’s bubbliest. Since 2007, home prices in the country are up nearly 84%. Robert Shiller, who won last year’s economics Nobel for his work on bubbles, says the Israeli market looks like a bubble. The IMF has warned that the probability of a “bust” is about 20%. In recent research, Goldman Sachs economists have spotlighted Israel’s outlier status, even among other countries that have seen “striking increases in house prices” since the global financial crisis (GFC).

Of course, there are plenty of ways to rationalize away the obvious, and argue that Israel is different and that the surge in housing prices is sustainable. And it’s true that Israel really is pretty different in a lot of ways. But that doesn’t mean that it’s not in a bubble.

Supply and demand

The main thing that makes Israel different is simple: There’s not a lot of usable land. A population of about 8 million lives in an area smaller than New Jersey or Sicily. But more to the point, the vast majority of land is owned, quasi-owned or administered by a state body, the Israel Land Administration. (More than 90% of it, according to the OECD.) And the state involvement makes for quite a bit of red tape, generating bottlenecks in the supply of new housing.

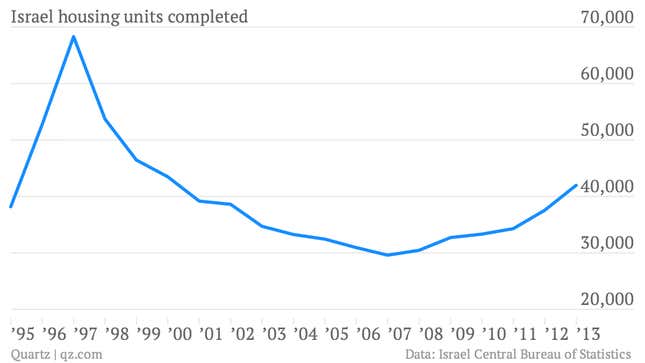

“Bottlenecks” might not be what you think of if you’re accustomed to hearing news reports about Israeli home construction in West Bank settlements. (In few other places are land-use decisions as freighted with historical, political, ethnic, religious, military, strategic, geopolitical and moral questions.) But building in settlements is only a small fraction compared to what happens in Israel proper. West Bank construction (not including East Jerusalem, though the rest of the world considers that part of the West Bank too) accounted for just 3.3% of the roughly 42,000 new dwellings completed in 2013.

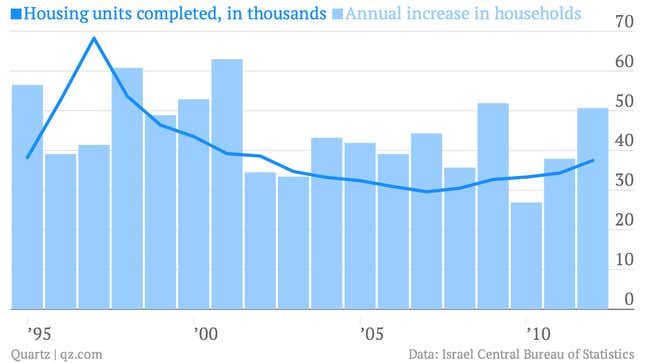

Homebuilding is rising in Israel. Last year saw one of the largest numbers of newly completed dwellings since 2000. That was the year the second Palestinian intifada broke out, cutting short an immigration and building boom that had been driven by the influx of immigrants from the former Soviet Union. But despite the recent uptick in home-building, the number of new households—in other words, of families needing a home of their own—is still outpacing the number of new homes being built.

Constrained supply? Strong demand? Sounds like a recipe for higher prices, no? It certainly doesn’t look like a bubble at first sight. Speculative bubbles are best thought of as faddish investor manias over a particular class of assets. Bubbles inflate when purchases are made in anticipation of seemingly endless price increases that don’t reflect the real value of the assets.

But in fact, there can be bubbles with convincing-looking foundations. Just look at the tech stock bubble of the late 1990s. The internet did indeed turn out to be the transformative technology it was touted to be, but tech stock prices soared and then abruptly crashed.

Why? What happens is that even if there’s a good reason for prices to rise at first, during a bubble price tends to become no object, at least for a little while. At the very minimum, the relative dearth of Israeli housing supply should act as something of a cushion for prices when they do turn. But it won’t keep them from turning. And there are indications that Israeli housing prices are starting to become a bit unhinged.

The ratios

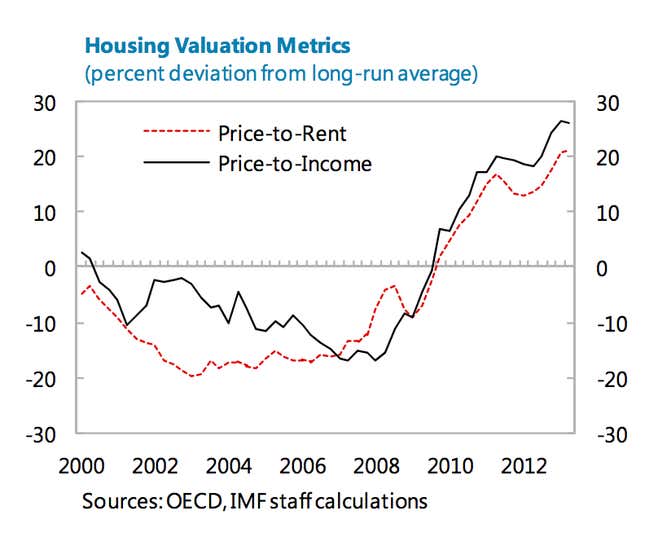

Some of those indications can be found in this chart, which comes from a recent IMF report on the Israeli housing situation. It looks at the long-term relationship between average housing prices and rents (the dotted red line), and between prices and disposable income (the black line). Rents and income traditionally act as a kind of anchor on housing values.

Rents are telling because they’re seen as a pure read on the value of housing services themselves. In other words, rents tell you what people will pay to actually live in a place. (Are the amenities nice? Are the schools good? Is the commute terrible?) Home sales prices are often more tied to the investment characteristics of housing (after you buy the house, will its value go up?) so they incorporate an element of speculation.

IMF analysts note the recent sharp divergence of these measures from their long-run averages. They estimate that, by these measures, Israeli home prices are roughly 20%-25% too high. They got a similar result when they estimated what housing prices should look like based on a range of economic inputs including wages, rental prices, the amount of mortgage debt outstanding, and the supply of housing.

“In addition, around 50 percent of the current house price misalignment is explained by supply-side constraints, while another 50 percent is accounted for by above-average growth in mortgage debt,” IMF analysts wrote.

Debt: The magic ingredient

There’s another reason to think that the rise in house prices isn’t just a result of high demand. The key question to ask is: “Where is the demand coming from?”

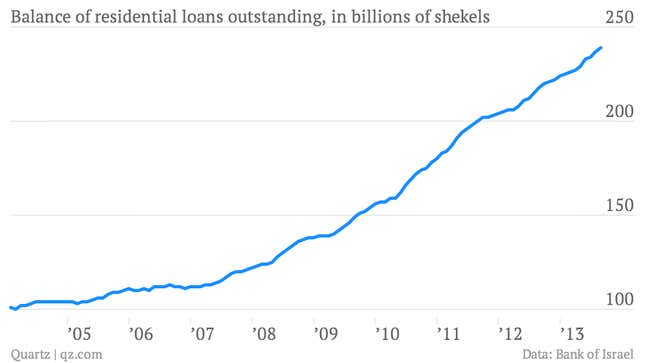

When it comes to housing, demand is intrinsically linked to debt. Israel’s market for mortgage debt has been exploding in recent years, as a side-effect of a low-interest-rate policy aimed at weakening the shekel and boosting Israel’s export sector.

Low interest rates make it possible for people to take out bigger mortgages. That increases the demand for housing, because it allows people to keep buying homes even as home prices rise. And as banks extend more and more credit to home buyers, they take on more and more risk.

The rise in mortgage lending, especially in riskier loans with high loan-to-value ratios (i.e., smaller down-payments), got the attention of Israeli policy-makers. Why? Because risky lending exposes the banking system—and by extension, the economy—to a number of problems if housing prices start to slide. (Just look at what happened to the US back in 2008.)

Even without a banking crisis, there are problems. For one thing, large home loans force people to spend more and more of their disposable income on housing, leaving less to be spent on everything else.

Regulators have acted to quell the rise in risky mortgage making. They’ve limited how much banks can lend in the form of variable-rate mortgage (since those mortgages are unpredictable, they’re riskier). And they’ve put caps on the payment-to-income ratio of new mortgages, so homebuyers don’t get too stretched. They’ve also restricted the loan-to-value ratios. For instance, people buying a house as an investment can only get a loan for half the purchase price. The restrictions are less stringent for first-time home buyers, but still only allow a loan for 75% of the value of the new home.

They’ve also taken steps, such as raising purchase taxes, to try to quell the rise in people buying homes for investment purposes, rather than to live in them. (Between 2003 and 2012 the share of Israeli households owning two or more homes increased from 3.2% to 7.9%.)

And still the lending continues to rise. In March new Israeli mortgages hit a record 4.5 billion shekels ($1.3 billion). (The amount did fall somewhat in April, when the Passover holiday likely weighed down demand.)

How does it end?

Nobody knows. The Israeli economy shows signs of slowing, thanks to a strong shekel and weak private consumption. (Some blame housing for devouring too large a share of disposable income.) That ties the central bank’s hands somewhat. If it tries to cool the housing market by raising interest rates (to make mortgages more expensive) it risks slowing the economy further.

Politics also plays a role. The high cost of housing was one of the factors that sparked mass protests in 2011, and politicians are under increasing pressure to find a solution to it. In March, a committee including prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu approved proposals to cap prices of new homes. That might put a damper on the surge in housing prices, especially for the foreigners who’ve poured money into the Israeli real-estate market in recent years. And it could be popular with the Israelis—especially young Israelis—who have found themselves priced out of homeownership in recent years.

But there are political pressures pushing the other way too. Any politician who engineers a tumble in housing prices after large chunks of the population dumped a lot of money into housing would be taking a big risk. Here’s what Shiller had to say about the resolution of Israel’s housing surge:

“I think that in the short term prices may continue to climb, but at some point it will turn around. It always ends the same way: prices become so high that people cannot afford them, at which point prices begin to fall and suddenly a lot of people decide to sell. When will this happen? Predicting bubbles is like predicting the success of a movie. I can show you the movie and ask you if it will be a hit. You’ll have your opinion, but it won’t be accurate. No one really knows.”