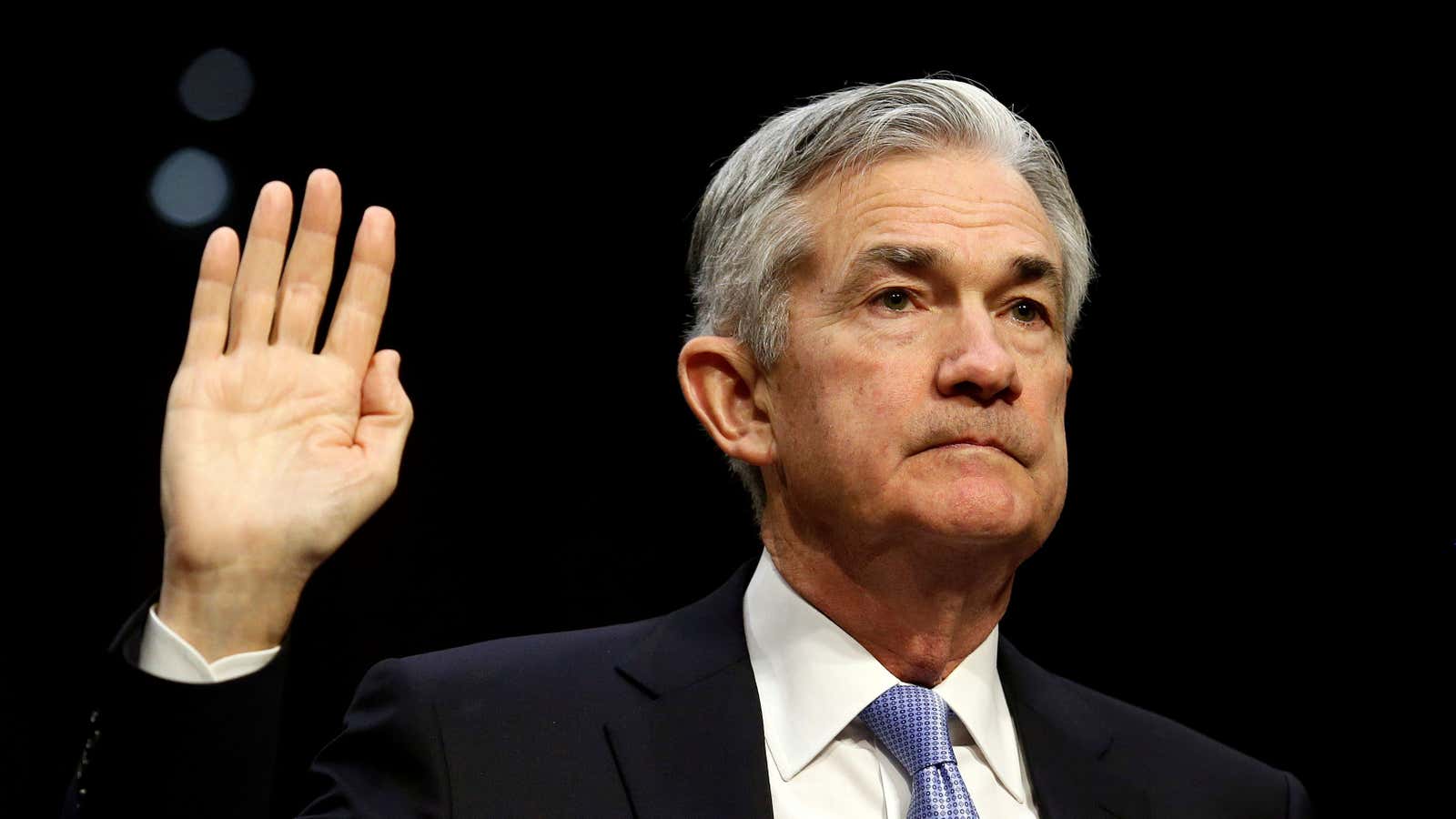

The last two years could end up looking like a breeze compared to what the next two might hold for US Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell. If confirmed, the Biden administration’s nominee for the top Fed job will face the most bedeviling monetary policy choices in decades.

Even as covid-19 halted economic activity and displaced millions of workers, what the Fed needed to do was clear: Loosen monetary policy and deliver historic levels of stimulus to keep the financial system afloat. But at this point in the pandemic, figuring out the right path is much more elusive—and treacherous.

The next Fed chair will have to parse through a tangle of mixed economic signals. Shoppers are out spending even as consumer confidence is at 10-year low and inflation grows. Supply chains are still ensnarled and covid-19 cases keep flaring up. Here are the top challenges Powell will have to navigate:

Beyond the Fed’s control

As far as economic recoveries go, this one has been unsteady given recurring waves of cases, said Grant Thorton’s chief economist Diane Swonk. That means the Fed’s margin for error for raising rates is unpredictable, and the potential damage of acting at the wrong time large. If the Fed tightens too soon, it could dampen demand that would have otherwise given more Americans jobs or higher wages.

Over the next six months or so, the Fed also has to determine whether or not the economy is able to work out the supply chain issues that are driving inflation. Most forecasting firms expect current constraints to ease by mid-2022, but a new variant of covid-19 or a natural disaster that upsets a key part of the supply chain could push that projection down the road.

And this time around, the Fed has no control over the best economic policy to fight inflation: vaccination rates.

Winning over inflation hawks

Powell and vice chair nominee Lael Brainard currently have similar dovish views of the US economy, Goldman Sachs noted in a recent research note. They both see inflation as transitory and they are both considering a wide number of factors when assessing what full employment means for the US.

But this doesn’t ensure the Fed will be able to hold off on tightening as long as both of them would prefer. Other central bankers on the Federal Open Markets Committee (FOMC) are still hardwired to think of inflation before maximum employment.

Striking the right balance

The central bank also has to gauge how low the unemployment rate can go before demand-driven inflation starts to kick up. The US economy was coming to the end of a decade long recovery from the Great Recession when the pandemic hit, and the country had not reached full employment before lockdowns began.

This recovery is happening quickly enough that Powell will likely have to determine what maximum employment—one of the Fed’s mandates—means. So far, Powell has urged humility on this point. Any missteps in measuring full employment could hamper the recovery.