Finally, some good news from the frontlines of the beeapocalypse: Significantly fewer honey bees died in the winter of 2013-2014 in the US than in previous years, according to a survey released today. Better yet, scientists think they know a simple way to minimize the devastation that has led to a $10 billion die-off of bees that pollinate one-third of the world’s food supply.

A host of factors have been fingered as culprits in bee deaths—from pesticides and a dearth of nutritious food to stress and even automotive exhaust. But researchers at the University of Maryland found that a well-known bee parasite, the Varroa mite, was the No. 1 killer last winter. “Our field data suggests mites are playing a very large role here,” Dennis vanEngelsdorp, a University of Maryland entomology professor who led the study, told Quartz.

Varroa mites are something out of an apian horror story. In a hive, the queen lays eggs in a honeycomb of cells. A female mite sneaks into the cell just before it is sealed by worker bees and lays her own eggs on the baby bee. Mites have a particular taste for the blood of worker bees, or drones, according to Ric Bessin, an entomologist with the University of Kentucky.

They suck the blood from both the adults and the developing brood, weakening and shortening the life span of the ones on which they feed. Emerging brood may be deformed with missing legs or wings. Untreated infestations of Varroa mites that are allowed to increase will kill honeybee colonies.

While scientists have spent years trying to figure out the role pesticides play in bee deaths, they’ve long known how to fight the mite: with a pesticide. If beekeepers are vigilant, they can spot a mite infestation and then treat it before it spreads.

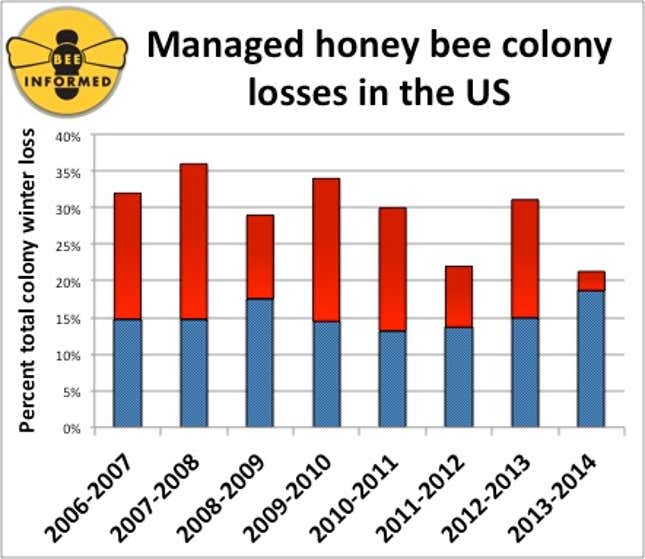

In the study of bee losses in 2013-2014, VanEngelsdorp’s team surveyed 7,183 beekeepers managing 22% of the US’s 2.6 million commercial honey bee colonies. He said people who run big bee operations in California did a better job of containing mite infestations than the managers of smaller colonies in the northeast. Here’s the percentage of bees lost for the past eight years. (The blue bars are what beekeepers considered an acceptable loss each winter; the red bars are the excess.)

Keeping mites at bay helped hold down the death rate to 23.2% of colonies in the winter of 2013-2014, compared to 30.5% the previous winter and an average of 29% since 2006.

Unfortunately, that doesn’t entirely solve the problem. The scientists also determined year-round death rates for colonies and were surprised to find a spike in bee mortality in the summer, when bees should be thriving. “We’re seeing levels of loss that we used to be think of as winter losses,” says VanEngelsdorp.

That can’t be explained away by mites, and vanEngelsdorp says that an interplay of pesticide exposure and the loss of plants and flowers that feed bees are probably contributing to the summer death rate. He and his colleagues last year authored a groundbreaking study that determined that bees’ exposure to eight agricultural pesticides increased their risk of infection by mites.

“If we took mites away we still would have these unexplained losses,” he says.